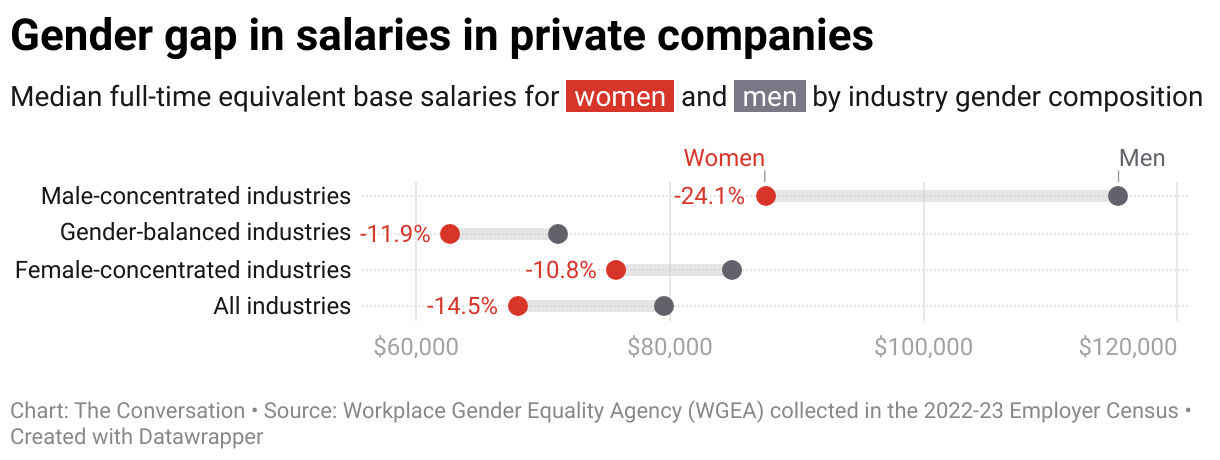

Men continue to outstrip women in the salary stakes, with men’s median annual salary $11,542 greater than women’s, according to newly released data for Australian private companies. It’s a gap of 14.5%, down from last year’s 15.4%.

Men’s median annual base salary in 2022-23 of $79,613 compares to $68,071 for women.

When bonuses and overtime are added — common for high-paying jobs mostly held by men — the gap in total remuneration widens to $18,461, equivalent to 19% and hardly budging from the previous year’s 19.8%.

This is the first time that the Workplace Gender Equality Agency, which annually reports gender pay gaps by industry, has released the names of actual companies and the differences in what they pay male and female employees.

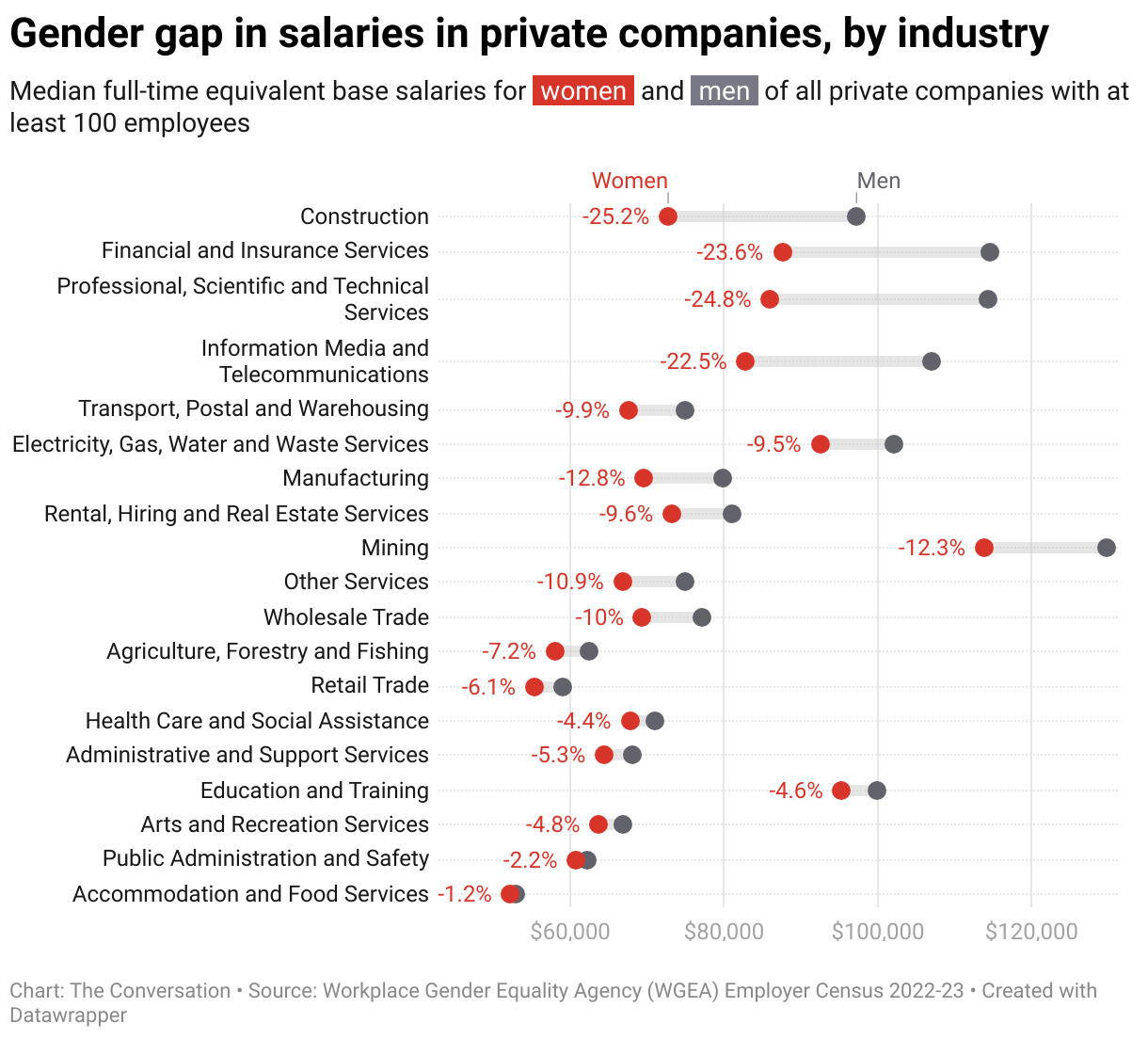

In this year’s snapshot released on Tuesday, the difference is largest in male-dominated industries (including mining, construction and utilities), with a gender gap in base salaries of 17.5%.

The WGEA data is based on the median of workers’ annual salaries in all large private companies in Australia. The agency includes all workers and converts the numbers into full-time equivalent earnings.

The gap, highlighted in these figures, is the difference between what men and women in each company earn overall, as opposed to the differences between what they are paid for doing the same job.

While the latest ABS figures for average weekly earnings released last week show women’s wages are improving, they are still lagging behind men.

Which industries and companies?

Companies have been required to report their gender pay gap to the WGEA for the past decade, but until now, these statistics relating to individual businesses have not been made public.

New laws mandating the publication of numbers mean we can now dive deeper into company spreadsheets and find out the size of the gender pay gap for every private organisation in Australia.

This data reveals that we can’t typify companies by industry. There are bad-performing companies — as well as good performers — across all industries.

Among Australia’s biggest employers, the retailers had relatively low gaps in total remuneration, with Woolworths reporting 5.7%, Coles 5.6% and Wesfarmers 3.5%. The mining companies had much bigger gaps, with BHP Group reporting 20.3%, and Rio Tinto 13.5%. Qantas reported 37% and Telstra Group 20.2%.

This new transparency is part of reforms passed last year to the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012, designed to spur companies to take more action on gender equity.

Of the almost 5,000 companies included in the WGEA report, almost 1,000 have a gender pay gap in median base earnings exceeding 20%. About 350 of these have a gap of more than 30% and for about 100, the gap is greater than 40%.

At the other end of the scale, there are about 1,000 companies where the pay gap favours women. These companies deal mainly in health, education and disability services where the high concentration of women means that senior roles are likely to be held by women.

Who does this data empower?

Pay gap transparency places public pressure on employers to do something about their gender pay inequities. It equips employees with more information to take into their salary negotiations. This tackles the problem of “asymmetric information” where employers know where each worker sits on the pay scale, but employees don’t.

Transparency gives customers and investors more information about whether a company is an equitable employer. They can use this new knowledge to make decisions about which companies to do business with.

This data empowers the whole Australian community. Any member of the public can go to the WGEA data explorer and search for any large private sector company to see the magnitude of their gender pay gap.

Supermarkets, banks, telecommunication companies, retailers, airlines, builders and energy providers are all on the list.

But new knowledge needs to be followed by action

While evidence on the benefits of transparency for closing the gender pay gap is promising, it’s not a silver bullet.

Firstly, while this public outing aims to spark stronger pressure on companies to take action, some companies will be more driven by public perceptions than others. Evidence of how widespread these gender pay gaps are could even normalise them, leading companies to reason they are not that out of step with others in their sector.

Secondly, there are risks in expecting individual women to use this new information to try to negotiate more strongly for a pay rise. Women still face the risk of backlash for showing assertiveness in bargaining. Being armed with extra data does not necessarily shield against these other gender biases.

Thirdly, even if women can bargain successfully, studies suggest pay transparency mostly empowers senior women. This was the outcome in UK universities where transparency led to more senior women securing a pay rise or switching to another higher-paying employer. Junior women with weaker bargaining power could not leverage this data in the same way.

Research shows that pay transparency can even worsen morale, productivity and perceptions of fairness if not also matched by clear explanations from employers on what actions they are taking to rectify inequities.

Employers and governments now have to act

With their gender pay gaps now in full view, the onus is on employers to adopt more equitable hiring, promotion and pay-setting practices.

This can even bring cost savings. After Denmark mandated pay transparency, the gender pay gap narrowed. Not because women’s wage growth accelerated, but because men’s faster wage growth slowed down. It means pay transparency can moderate employers’ wage bills.

While greater transparency of information is empowering, it alone will not be enough. It needs to be accompanied by actions. The fact Australia’s gender pay gap has endured, even over 50 years since equal pay was enshrined in law, reflects a combination of society-wide factors, family dynamics, organisational culture and practices, and policy settings.

Actions also need to include evidence-informed policy, such as increasing access to affordable child care and expanding paid parental leave, to close the gender pay gap for good.

This piece was first published in The Conversation.

You can’t be serious. You…can’t. This is just embarrassing. THIS…is your ‘gender pay gap’???? This…methodologically-unhinged jumble of reverse-engineered claptrap? One might as well rail against the ‘pay gap’ between hospital anaesthetists and hospital porters. Between ABC Managing Directors and ABC telephonists. Between newspaper editors and newspaper deliverers…really.

No-one with a brain and a jot of academic self-respect – of any gender – could possibly swallow this anti-empirical garbage.

Well said.

The authors seem to be rather incurious. They have collected statistics showing pay gaps, but stop at noting the gap rather than asking any questions like “How does this happen?” or “What’s causing the gap?”. I’m guessing that there are different reasons (Note: not necessarily valid reasons.) for different industries and different mechanisms for achieving the gap.

During the early part of my working life I started as a junior in an HR team, surrounded by more experienced and knowledgeable women. After about 4-5 years I was leading the team. Why? For the simple reason that most of those more experienced women took time off to have babies and then came back part-time. None of them wanted the team leader role because it was a full-time position.

Later on I worked in IT. The technical jobs paid well. There were very few women in those jobs. Why? Discrimination? No, they never applied. We would have been happy to have a more even balance of genders, but short of press-ganging women that was never going to happen. In addition, most of the jobs that resulted in significant overtime and (for instance) on-call allowance for being on standby during nights and weekends were avoided by women.

Look. I understand that those are anecdotal. I’m not a researcher, I’m just reporting what I’ve seen. But those are two more explanations than the writers have provided for a gender pay gap, for a total of three times as many (since they did mention overtime and bonuses).

I look forward to a future article where they or their colleagues drill down and look into things like length of service, hours worked and why (because, yes, women are for instance often expected to be the ones picking up children from school rather than men and that should be more fairly apportioned), how much of the various factors causing the pay gap are voluntary, how much is down to plain simple gender discrimination, and a myriad other reasons an old man may not be aware of.

Measuring the size of the gaps is a small start. Knowing why and how the gaps exist is the more important job.

The methodology behind this is absurd to the point of being counter-productive.

An interesting statistic.

Of course, you know what they say about statistics.

There’s lies.

There’s damned lies.

There’s stupidity.

Then there’s economists.

As someone who know the workings of the big fours quite intimately, and seeing the results for PWC, EY, KPMG and Deloitte I think this survey does have something.

Each of these firms of similar size, structure and marketplace, have very varied wage equity measures.

The differentials of median base salaries are 4% 14% 16% and17% with PWC being closest to equity.

They must be doing things differently.

Now consider if you were a woman, seeking work with the big four. Which firm would be you first choice, all else being equal?

Given those firms compete strongly with each other, for the talent they need for their lucrative projects, it is a smart move if you can show your company to be more attractive to women.

I am not sure as a male I’d be wanting to go to the other firms either. Why would I not want to be working with the best talent?

Is not that a win win? And isn’t that what this survey is about?