Ex-cyclone Gabrielle’s “extreme, impactful, and unprecedented weather” is causing panic, fear, and danger in New Zealand’s North Island after record-hot ocean temperatures created an atmospheric pressure cooker.

Some 50,000 homes and properties were plunged into darkness overnight as the storm, described as the most serious to hit New Zealand in a century, pelted down up to 400mm of rain and blew winds at up to 160km/hour.

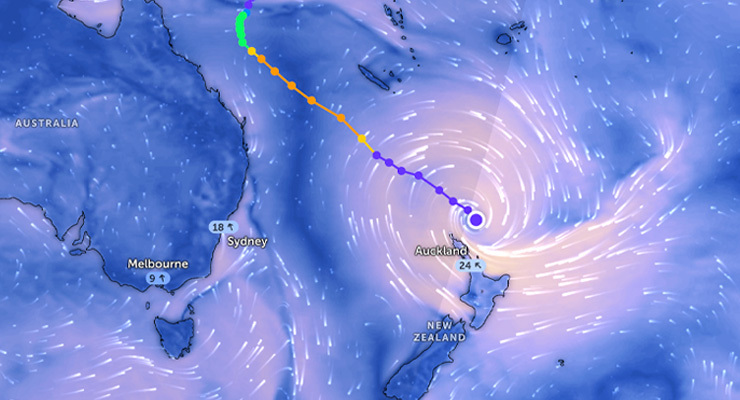

The torrid centre of Gabrielle, now downgraded to a sub-tropical low-pressure system, is forecast to close in on the North Island during the next 36 hours, just weeks after Auckland emerged from its wettest month in over 170 years.

Four people were killed in landslides and flash floods after residents in the country’s most populous city were caught off-guard by an entire summer’s worth of rain pummelling down in one day on January 27 — some 240mm worth.

On Saturday, Waka Kotahi national emergency response team spokesperson Mark Owen warned the weather-weary residents in the North Island to brace for more devastation.

“Many roads in these areas were damaged in the previous storm, the ground is already sodden, and they are particularly vulnerable to slips, flooding and closure,” he said.

Why is this happening?

Ex-cyclone Gabrielle is passing over ocean waters surrounding New Zealand’s north that are up to 2 degrees warmer than usual, (swaths of the South Island’s surrounds are as much as 6 degrees warmer than usual right now).

The reason? A marine heatwave in the Tasman Sea and around New Zealand, Metservice oceanographer Joao Souza tells Crikey.

“The rate of warming is above the global average since 2012-2013, with the last two years presenting record-breaking ocean temperatures leading to unprecedented marine heat waves around Aotearoa,” he said.

“This means that more heat (energy) is available in the ocean. All this heat and moisture are transferred to the atmosphere as storms blow and mix the top water layers.

“This process fuels the tropical cyclones travelling over the warmer-than-normal waters, potentially delaying their fading and increasing coastal precipitation.”

The heatwave is caused by a few different things: intense high-pressure systems turbocharged by our rapidly changing climate, occurring within the context of three consecutive years of La Niña.

The hot, wet La Niña system creates ideal conditions for tropical cyclones during the season (November to April), the Bureau of Meteorology says, with twice as many making landfall than during El Niño years.

What happens now?

It could be about to get worse. WeatherWatch says Gabrielle’s air pressure is expected to drop in the next 24 hours, intensifying the storm as it moves closer to land with a forecasted peak before dawn on Tuesday.

“This system poses a very high risk of extreme, impactful, and unprecedented weather over many regions of the North Island from Sunday to Tuesday,” weather forecaster MetService said.

It comes as newly minted Prime Minister Chris Hipkins listed climate change and resilience as his top two priorities this week ahead of an online cabinet as he remains grounded in Auckland.

When prodded about whether government permissions to build in flood plains should be revoked in light of Gabrielle’s landfall, Hipkins said he couldn’t think about that right now: the country was still in a response phase rather than recovery.

“We’ve got to just make sure we’re getting people through what is likely to be a pretty difficult 48 hours or so.”

Please, Crikey, can writers be given a short courses on the correct uses of less and fewer and of number and amount. Any experienced TESOL could help.

I was reading a piece on Crikey recently that referred to the ‘amount of babies’ born with FAS. Like they had been shovelled onto the scales, somehow.

Absolutely agree, MJM. Even the ABC announcers are guilty. A sad gap in teaching English over the last30 years . ..

“Panic and fear” in kiwi land? Don’t think so. P and f off, in fact. Climate journalism is always welcome, if it sticks to facts rather than beat-ups. It’s a responsibility.

I have been predicting that increased wind activity will be a result of climate change at least as important as temperature increases. The more energy you put in a system the more its bits move around. I am looking at domestic wind power as well as solar as a result.

If you want to give yourself a fright calculate the increased amount of energy that is stored by increasing the temperature of a patch of ocean 1,000 kilometres by 1,000 kilometres 1,000 metres deep by 1 degree Celsius and and then compare that to Australia’s annual energy consumption of around 6,000 petajoules. Then consider transferring some of that to wind.