There appears to be a blissful collective hallucination among my learned fellow Crikey columnists surrounding the cause and solutions to Australia’s inflation problem.

That is, repeated claims that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and supply chain challenges have caused recent price rises (inflation clocked in at a 35-year high of 7.8% in January). And hence that the RBA increasing interest rates is foolhardy because it won’t reduce inflation anyway and will harm Australian workers.

This is magnificently wrong on every count.

Supply-driven inflation can absolutely be a thing. Take the 1973 oil crisis, which saw the oil price increase from US$3 to US$38 a barrel. In most cases, cost-push inflation is rarely a long-standing problem. In time consumers find substitutes, and in the medium term they change behaviours (higher oil prices led to consumers switching SUVs for smaller, more efficient cars, for example).

Most inflation is demand-driven: too many dollars chasing too few goods (and caused by excessive debt). This is the case now, and blaming COVID or supply chain issues is to be blissfully ignorant of the actual data.

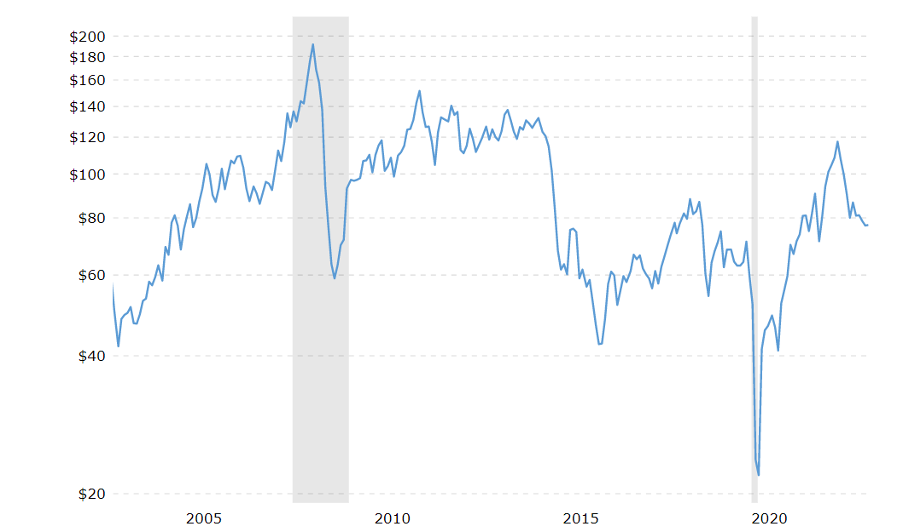

Let’s look at oil, arguably the commodity that most impacts inflation (especially at a consumer level). Oil is well below its peak (below is a graph tracking the inflation-adjusted crude oil price). Other than a few brief moments in 2015 and 2017, you need to go back to 2005, prior to the 2007-08 global financial crisis, to see sustained lower prices:

It isn’t just oil that has reverted to the mean. Lumber costs, a key ingredient in building, have fallen by almost 80% to trend at pre-COVID levels:

The Baltic Dry Index, which tracks the costs of international shipping and is a key indicator of trade demand, is down 77% and back below pre-COVID levels:

The notion that inflation is supply-driven is simply not justified by the data. For example, the main reason building remains so expensive is the difficulty in sourcing labour. (This will adjust in time, when residential and commercial building starts falling and skilled immigration returns.)

While the Reserve Bank got it wrong for almost a decade when it kept interest rates far too low, RBA governor Philip Lowe is getting it half right in raising interest rates (although rates should be far higher than the historically low 3.6% they remain).

Moreover, the notion that higher interest rates are somehow an attack on the lower class or working poor is nonsensical.

Higher rates impact leveraged asset owners, especially those with multiple investment properties or leveraged operating businesses. As the cost of debt increases, the value of these assets usually declines (witness the recent falls in residential housing and share prices).

Similarly, the past two decades of irrationally low interest rates (in most cases, below the level of prevailing inflation), have led to an unprecedented run-up in almost every asset class, from residential property to cryptocurrencies to art and other luxury goods (for a brief period, Bernard Arnault, CEO of luxury good supplier LVMH, was recently the world’s richest person).

For those who don’t own assets, like younger people who cannot afford to buy a property, rising interest rates are a triple benefit. First, it reduces the net cost of assets like housing (and means less debt is needed in the first place). Second, higher interest rates reward savers (like those trying to accumulate a deposit). Third, higher rates lead to lower demand-pull inflation levels, which means real wage growth (that is gross wage growth, less inflation) improves (or more accurately, less bad).

The bizarre argument that has circulated in Crikey and proffered by Greens Senator Nick McKim (who himself owns multiple investment properties), that higher interest rates harm the young and the poor, is self-serving tripe. One suspects if you created a Venn diagram considering wealthy property owners and those demanding Philip Lowe be sacked for daring to increase rates, there would be a very significant overlap.

Interest rates naturally should remain 2-3% above the prevailing underlying inflation rate (they remain almost 4% below it), anything else penalises savers and rewards asset-owning speculators. Rest assured, even with 10 consecutive rate rises, policy settings remain highly expansionary.

Have economy-watchers got the wrong idea on inflation and rate rises? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Leaving aside the nasty ad hominem against Sen McKim’s ownership of investment properties, Schwab simply misrepresents his view about why interest rate rises alone are an inappropriate response to inflation. McKim’s point — backed up by a report from the Australia Institute — is that we are witnessing a PROFIT-price spiral, not a wage-price spiral.

Many of the ‘too few goods’ that Schwab says the ‘too many dollars’ are chasing are not optional. Thus the grocery duopoly of Coles and Woolworths have both reported increased profit margins. Now, the Reserve Bank might make some mortgage holders miserable enough with their rate rises that it will dampen enthusiasm for eating. But somehow I think the potential for that is limited. And in any event, if this were a simply a case of too many dollars chasing too few goods, why would the grocers’ profit margins be up?

Furthermore, Schwab simply asserts that higher interest rates are good for savers, but he fails to note that banks have been extremely reluctant to offer higher interest rates to savers. CBA’s profits are up 10% on the back of Net Interest Margin rising to 2.1%.

If I want to read nasty ad hominems against the Greens by people peddling neo-classical smokescreens for corporate greed, I can read the Fin Review. I don’t need to see such shrill and utterly implausible twaddle on the pages of Crikey.

Yes, it’s a while since we’ve had some classic Schwab contrarian capitalism. Damn those not very useful eaters. I would not want to be Governor of the Reserve Bank trying to get to sleep at night, there is some terrible suffering out there.

Yes, the article is all over the place. I can accept the too few goods side of the equation but given there’s no wage/price spiral I don’t buy the demand side. A 2 data points isn’t much evidence.

I suppose if you consider ‘less profit’ to be the same as ‘less to live on’ then Adam’s right, it’s not just the young and poor that are affected by interest rate rises. But the rich can always sell off one of their investment properties; as you say, when it comes to the poor, they can only try eating less.

Super profits are largely the result of consumers’ (average, admittedly) willingness to pay, i.e., too much money available, due to both CoViD stimulus and historically low interest rates.

Indeed. Food, petrol, medical care, etc, all well known as “luxury goods” for status-seekers.

Spot on.

If you can find a young person who has said recently that high interest rates have made their fixed rental costs drop or the price of food drop let us know. It aint happening in the real world. And those with the least incomes will suffer from those kinds of unavoidable costs rising. Also I don’t notice the price of housing magically becoming affordable to first home buyers. It’s still ridiculously high. I feel like there is no-one in the reserve bank that really feels the pinch of what they are doing. And often stunned that its the one area of the economy where we are supposed to let the technicians decide when we can’t seem to do that on capital gains tax, negative gearing tax, windfall profits or basically anything that makes the big end of town pay. Pain always seems to be most useful when inflicted on the lower end of the income and wealth scale, never on the upper end.

Oh, for some upper-end *PAIN*

“ Do I go for the Merc or the BMW? Oh! My head hurts!”?

Is “too few goods” not a supply problem ? Surely the better solution is more goods rather than fewer dollars ?

The author is trying to have his cake and eat it, too, by first defining “the young and poor” as being unable to afford a mortgage and therefore unharmed by interest rate rises, but later using them as an example of beneficiaries because they’ll be able to earn more interest saving a home deposit.

The only difference between people still saving a deposit and people who bought a home in the last year or two about to be sent bankrupt by interest rate hikes is time.

Further, it seems likely that the people still spending merrily are old Gen Xers and Boomers, because they’ve either got no mortgage at all, or a very small one. Interest rate hikes will do nothing to slow them down and may even have the opposite effect given increased earnings from savings.

Finally, the consensus around inflation at the moment is it’s being driven mostly by corporate profiteering.

Agreed. Schwab’s logic is awry!

And yet, Schwabb, the RBA’s own analysis says up to 75% of the inflation problem is caused by supply problems. That analysis was based on December data. Maybe you should check the RBA’s research and, while you’re at it, reflect on comments by Lowe in Senate Estimates before you treat readers to yet another round of self-serving, ignorant, right-wing bs.

You expect Adam to do actual RESEARCH?!?! He never did it when attacking the pandemic response (because it was hurting his vested interests), so what makes you think he will do it here?

You’re right, of course. Silly me. Schwab never has, and never will, impress anyone with anything approaching an intellect.

Good to see this article in Opinion rather than Analysis/ Economics. Thanks Crikey.