More than a year into Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, there are few signs the conflict will end any time soon.

Ukraine’s success on the battlefield has been powered by the innovative use of new technologies, from aerial drones to open-source artificial intelligence (AI) systems. Yet ultimately the war in Ukraine — like any other war — will end with negotiations. And although the conflict has spurred new approaches to warfare, diplomatic methods remain stuck in the 19th century.

Yet not even diplomacy — one of the world’s oldest professions — can resist the tide of innovation. New approaches could come from global movements, such as the Peace Treaty Initiative, to reimagine incentives to peacemaking. But much of the change will come from adopting and adapting new technologies.

With advances in areas such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, the internet of things, and distributed ledger technology, today’s emerging technologies will offer new tools and techniques for peacemaking that could impact every step of the process — from the earliest days of negotiations all the way to monitoring and enforcing agreements.

From people to techno tools

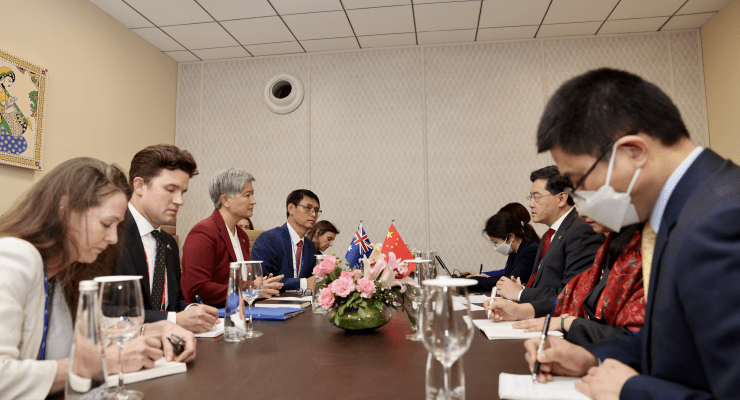

Although the well-appointed interiors of Vienna’s Palais Coburg and Geneva’s Hotel President Wilson are likely to remain the backdrop for many high-level diplomatic discussions, the way parties conduct these negotiations will undoubtedly change in the years ahead.

One simple example is the need for live language interpreters. The use of automated language processing — as exemplified by Google’s language-translating glasses — could smooth negotiations, reducing the time spent on consecutive interpretation.

While some tools will speed negotiations, others will better inform diplomats ahead of talks. As Nathaniel Fick, the inaugural US ambassador at large for cyberspace and digital policy, recently quipped, briefings generated by the AI-powered ChatGPT are now “qualitatively close enough” to those prepared by his staff.

As large language models improve, AI will be able to search and summarise information more quickly than a team of humans, better preparing diplomats to enter negotiations.

Although these systems will need some degree of human oversight, allied parties can also compare notes, leveraging their respective AI systems. As more and more parties develop their own AI, we could see “AI hagglebots” — computers that identify optimal agreements given a set of trade-offs and interests — take on a key role in negotiations.

Ever more sophisticated AI systems may even one day reach a level of artificial general intelligence. Such systems could upend our understanding of technology, allowing AI to become an independent agent in international engagements rather than a mere tool.

As negotiations begin, parties may augment their delegations with AI, providing real-time, data-informed counsel throughout discussions. IBM’s cognitive trade adviser has already assisted negotiators by responding to questions about trade treaties that might otherwise require days or weeks to answer.

New technologies also allow countries to solicit citizen input more easily in real time. More than a decade ago, Indonesia pioneered a platform called UKP4, allowing everyday citizens to submit complaints about anything from damaged infrastructure to absent teachers. Although technology can be misused for manipulation and misinformation, artificial intelligence can also serve as a powerful tool to identify these misbehaviours, creating an ongoing struggle in the arms race between AI that will help and AI that will harm.

Intelligent systems can also help negotiators test various positions and scenarios in a matter of minutes. During the first round of Iran nuclear negotiations, a team at the US Energy Department built a replica of an Iranian nuclear site to test every permutation of Iranian nuclear enrichment and development. In the future, an AI system will be able to run similar scenarios and virtual experiments faster and at a much lower cost.

When I worked on then US secretary of state John Kerry’s team negotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2014 and 2015, diplomats would meet in a variety of configurations — from large plenaries to one-on-one sessions — trying to discover the intentions behind the positions each side took and discern even minor differences among individual negotiators. While traditionally the privy of the espionage community, computer vision can now aid in this effort, identifying micro-expressions and other emotions by analysing videos of negotiations. Even if diplomacy remains an art, it will increasingly rely on hard science.

When negotiators reach an agreement, they need to secure the support of their capitals and leadership, creating the need for secure communication. Negotiators have long faced the risk of spies and leaks and are now more exposed than before to the threat of intercepted calls and cybersecurity breaches.

New technology can both secure communication and put it at risk. Most strikingly, powerful quantum computers are likely to one day crack present-day encryption. The furor caused by the WikiLeaks revelations would pale in comparison to the bedlam that could unfold as foreign intelligence agencies decrypt thousands of confidential diplomatic cables.

As of today, many intelligence agencies are probably already intercepting and storing cables with the hope of decrypting them once they develop the requisite technological capabilities. In response, countries have developed new techniques to ensure the integrity of diplomatic communication through post-quantum encryption. In a December 2022 demonstration, French President Emmanuel Macron sent the French diplomatic service’s first quantum-secure telegram.

Technology’s role after the deal is done

After parties announce a deal, technology can still play a role in ensuring their agreement enters into force.

When the JCPOA went into effect in January 2016, the US had difficulty releasing Iranian assets frozen after the revolution — banks were still afraid to transfer money for fear of running afoul of the sanctions’ regime. In the end, the US government delivered $1.7 billion in cash to Iran, flying $400 million on pallets to Tehran through Switzerland.

Distributed ledger technology has the potential to transparently ensure parties receive compensation and could be used to openly transfer funds while keeping in place sanctions for other purposes. Already blockchain is showing its promise across a variety of use cases, including transferring information securely out of Ukraine. Working together with social enterprise company Hala Systems, a lab at Stanford University has used blockchain to document Russian war crimes, ensuring that original evidence of war crimes cannot be manipulated.

After agreement and implementation, monitoring is key to ensuring an agreement holds. In 2015, Iran agreed to a monitoring regime of unprecedented rigour. As Kerry explained at the time: “Iran’s nuclear program will remain subject to regular inspections forever.”

In the future, the internet of things — or the ability for items of daily use to be connected to the internet — may make such inspections far more effective by creating many new data points. Teams at Los Alamos National Laboratory, for example, have already used AI to detect signs of nuclear explosive tests by relying on data from international sensor networks.

Remote sensing can also play a role in ensuring parties follow through on their commitments. For example, once the exclusive domain of intelligence agencies, a team at Stanford has now used open-source geospatial imagery to monitor activity at Iran’s nuclear facility in Natanz. Once quantum sensing matures, it will become even more difficult for malicious actors to disguise their activities.

Quantum sensors have already proven successful at mapping underground tunnels and identifying seismic activity. Granted, some of these applications are still far in the future; in any upcoming negotiations, monitoring will have to rely on more traditional methods. But the promise of these new technologies is vast.

Although our ways of waging war have evolved, our ways of waging peace have not yet made similar strides. Ukraine’s defence has laid bare the importance of bringing innovation to the battlefield. Its success at the negotiating table will be in no small part a result of technological innovation too.

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

I wonder how soon quantum sensing will be able to detect a nuclear-powered submarine at maximum depth…

Only time period fractionally shorter than it will take to find a counter for quantum sensing to enable submarines to be hidden from quantum sensing. Measure, counter-measure, next measure, repeat. Been that way for millenia.

I estimate maybe 10-15 years before we have both the technology to see any large physical body like a submarine in the ocean and the drone capability to take it out anywhere in the world. Star Trek was set some two centuries from now and their cloaking capability is likewise still way beyond the understanding of physics we have today.

I would say a good lie detector would be an essential in dealing with Putin.

Whereas it would be totally superfluous with the likes of Morrison, where it always is a safe bet to assume the are lying. No fancy technology required for that.

Your irrational aspersion of Putin may have many causes but one thing he does not do is lie.

Pity that the West’s so-called ‘leaders’ did not listen to his clearly expressed concerned since 2014.

If we start letting AI run diplomacy how long before we end up in the Star trek episode “A Taste of Armageddon”?

And the big, rich nations (eg Australia) will use AI to screw poorer nations (eg East Timor) even more effectively.