No one likes spending cuts and tax hikes, but on our estimate the government will soon need more of them if they are going to make a dent in looming $70 billion a year budget deficits.

A new Grattan Institute report, “Back in Black? A menu of measures to repair the budget“, argues the present combination of low unemployment and high inflation makes this a good time to start to put things in order.

The sooner we do, the sooner we will be well-placed to respond to future economic shocks and avoid pushing costs onto future generations.

We were right to spend big when COVID hit

The massive government support unleashed during the 2020 and 2021 lockdowns was essential for supporting households and businesses and helped keep unemployment low and Australia’s 2020 recession mild.

It left us with government debt that, at 23% of GDP, set to climb to almost 32% by the end of the decade, is high by historical standards, but low by international standards.

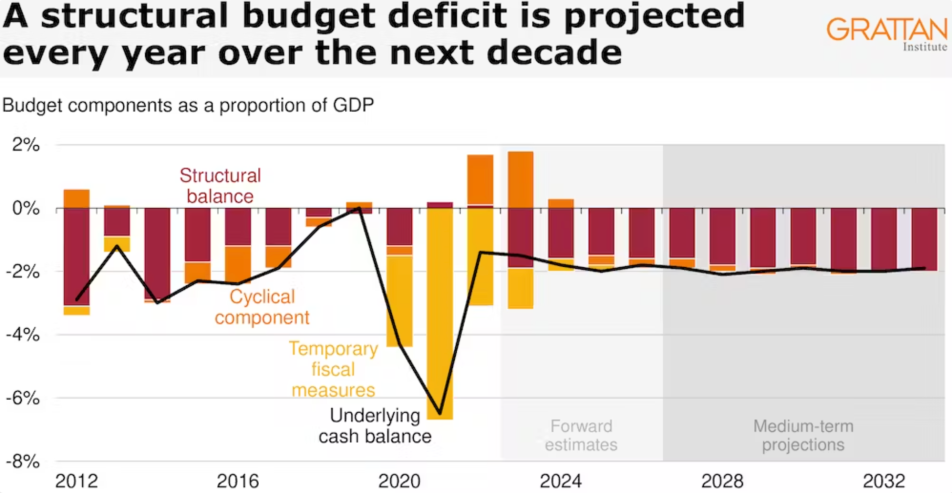

Our real problem is a structural one of spending growing faster than revenues. And it was building long before COVID.

Demands on government are set to grow

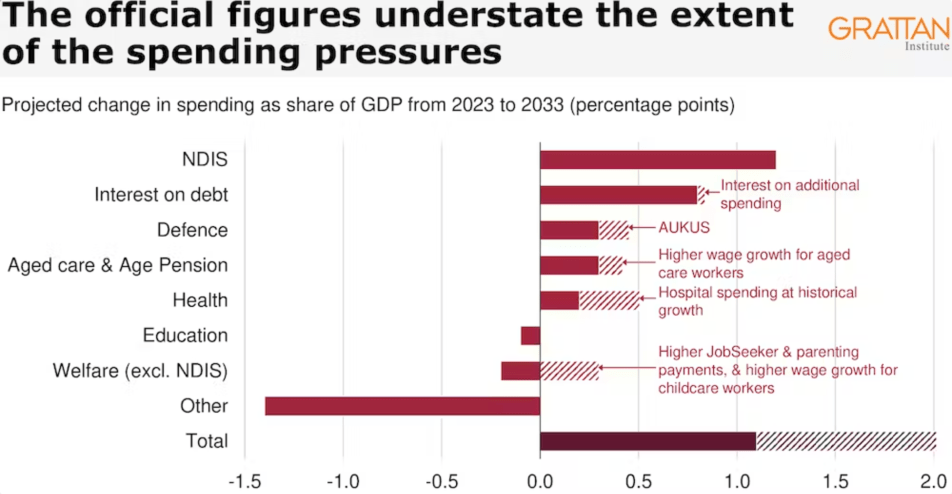

Costs are inexorably growing for three reasons.

The first is that our expectations are growing as we age and become more wealthy, pushing up spending on healthcare, disability care and aged care.

The second is that many of these services happen to be the hardest to mechanise, meaning there is little we can do to stop them costing more over time.

The third reason is geopolitical and climate developments. The huge AUKUS deal is just the latest manifestation of pressure to ramp up defence spending. Increases in the frequency and severity of natural disasters mean we have no choice but to spend more on emergencies than before.

Combined with higher interest rates that are pushing up the cost of servicing debt, these three forces are set to leave a persistent gap between government revenue and spending of about 2% of GDP according to Treasury calculations. That’s $50 billion per year in today’s dollars, each and every year.

But even that grim forecast looks optimistic.

Grattan Institute estimates suggest the true structural gap exceeds $70 billion per year when extra, largely unavoidable spending is taken into account — including on AUKUS, overdue wage rises for care workers, more realistic growth in hospital spending, and long-overdue increases in unemployment benefits.

And that’s just the next decade. In the longer term, the budget will come under extra pressure from slower productivity growth, Australia’s ageing population, and climate change.

Higher economic growth and productivity growth would reduce the enormity of the challenge, and Grattan Institute has put forward ideas about how to support this before.

But hoping we will be able to grow our way out of chronic budget deficits is not a prudent approach. While we should try to boost growth, by itself it is unlikely to get the nation’s finances onto a sustainable trajectory.

13 multibillion-dollar ideas

The size of the problem, and the political difficulty of budget repair, mean both spending and revenue measures need to be on the table.

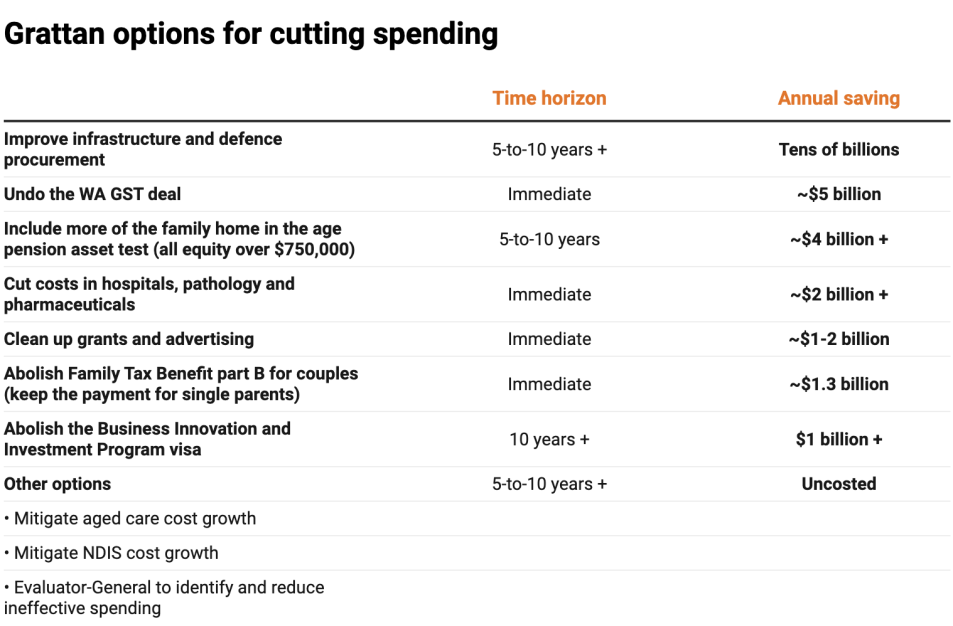

Spending cuts have been the focus of budget repair efforts for most of the past decade, so a lot of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. But there are still savings to be had.

The biggest would come from greater discipline in decisions about what to spend on infrastructure and defence. Better decisions upfront based on economic — rather than political — considerations could save several billion each year.

Buying smaller, more regularly and “off the shelf” would reduce the risks and costs of mega-projects that have a history of massive cost overruns.

Our report identifies a further $15 billion a year of savings measures, including undoing Western Australia’s special GST funding deal, counting more of the family home in the age pension asset test, and improving hospital efficiency and purchasing in health.

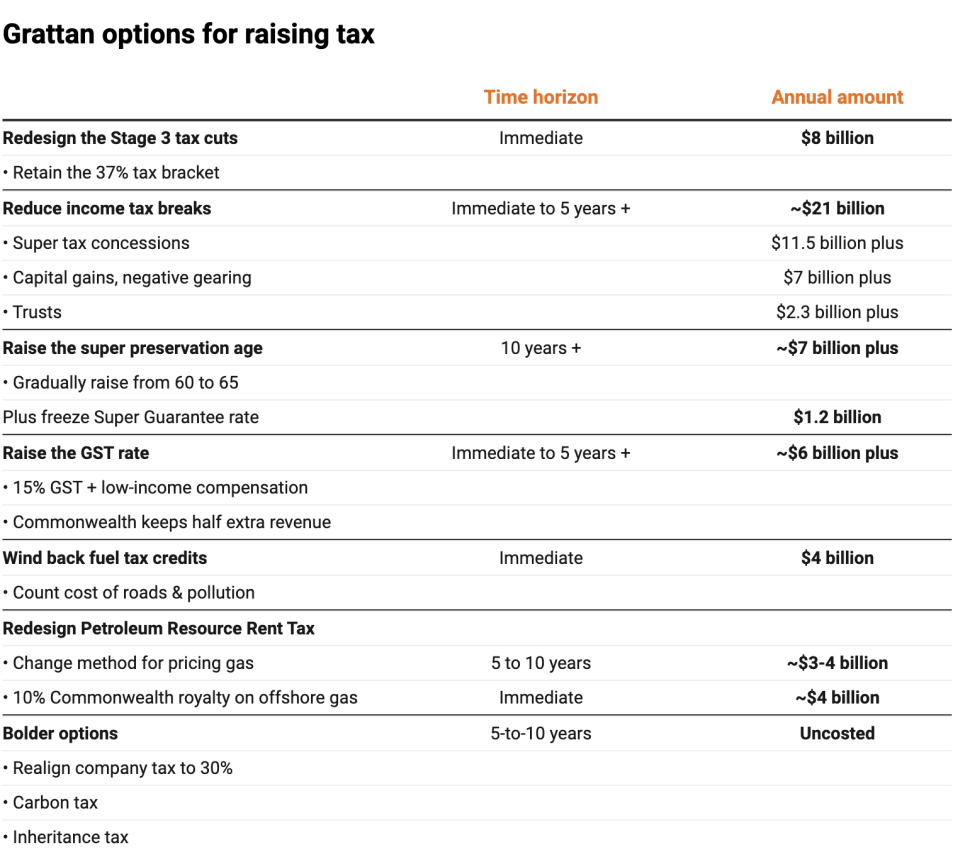

But even with substantial spending cuts, tackling Australia’s budget challenge without compromising core services will require more revenue.

The biggest opportunity comes from plugging “leakages” in the income tax system. Tax breaks and minimisation opportunities are growing. Reining in superannuation tax concessions, reducing the capital gains tax discount, limiting negative gearing, and setting a minimum tax on trust distributions could collectively raise more than $20 billion a year.

Reworking the legislated stage three tax cuts so they are less generous at the top end would save another $8 billion per year.

Lifting the age at which people could get access to their super from 60 to 65 and freezing compulsory super contributions at their present level (10.5% of salary) would save at least another $8 billion.

Other options include lifting the rate of goods and services tax (with a compensation package, and the Commonwealth and states sharing the net revenue), winding back fuel tax credits and beefing up the petroleum resource rent tax.

Ordering the whole menu at once would be a recipe for indigestion. But if Treasurer Jim Chalmers chooses just a few items on the menu, we will be well on the way to tackling Australia’s budget problem.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

My first choice for fixing the budget is including all bequests or inheritance received as taxable income. (Therefore not a tax on the estate of the deceased and not a so-called ‘death tax’.)

Bequests have become excessive, exacerbating the differences between honest and privileged youngsters. If the tax breaks involved in superannuation were re-categorised as “delayed taxes”, they could be completely recouped when the (non-) taxpayer dies. Without massive windfalls from some of our oldies, our descendants would work and play on a more level playing field.

Counting more of the family home (over $750K) in the age pension asset test might sound fair to some people but it is not. Several Pensioners live in houses valued at more than $750K. In other words they are asset rich but cash flow poor.

You cannot eat a house. They would be forced to sell their home of 20, 30 or more than 40 years and move away from their support structures such as friends, .supportive neighbours, GP, chemist, home care service etc.

Are these people expected to sell their home and move to a totally different area, become socially isolated and lose all that support?

There are various ways to get an income from a personal home without moving out, including ther government’s Home Equity Access Scheme. So these unfortunate ‘asset rich but cash flow poor’ pensioners are in that position by their own choice..

Anyone remember the War Service Home Loans? Now a Westpac scam/fiefdom called Defence Home Ownership Assistance Scheme (DHOAS).

Simplest solution is Death taxes – maybe then Gen Yechhs & Zero will learn some responsibility.

Dunno why the first version was AWAITINGED.

Hear the howls of rage from the grasping offspring as they see ‘their’ money being frittered away keep the oldies alive and comfortable.

As long as a Home Equity Access Scheme remained in government hands – it would a prize much desired by the usual suspects for privatisation should they ever have a chance.

The grasping offspring would freak as they see ‘their’ money being frittered away keep the oldies alive and comfortable.

As long as a Home Equity Access Scheme remained in government hands – it would a prize much desired by the usual suspects for privatisation should they ever have a chance.

As long as a Home Equity Access Scheme remained in government hands – it would a prize much desired by the usual suspects for privatisation should they ever have a chance.

Think of how the children would react to see ‘their’ money being frittered away keep the oldies alive and comfortable.

Educate the children. It’s not THEIR money.

Have you not heard of the Age of Entitlement?

The last 3-4 generations (give or take) have been brought up to expect all kinds of everything on a gold platter and would be outraged were it only offered on a silver one.

The sooner large numbers of people learn how to cook basic foods, live with the arse out of their strides, holes in their shoes and eschew $5 coffees the sooner they’ll wake up…zzzzzzzz

https://historyhustle.com/2500-years-of-people-complaining-about-the-younger-generation/

I’m struggling to see how death taxes, so called, are simpler than including any bequests with taxable income. It could be done by just adding a few words to the definition in the income tax legislation. It would not only apply a very significant tax rate on inheritance, it would be progressive as those who already have a sizeable income and receiving the largest inheritances would pay the highest rate, while anyone with no income could inherit up to the taxable allowance of about $18,000 tax free. This would encourage the wealthy to spread it about a bit among their younger and more impecunious descendants, which would be no bad thing.

I was thinking more about the welfare of the current holders of the moola rather than the greedy descendants.

The latter I regard as I do the Unspeakable chasing the Inedible – apart from Reynard, I’m happy to discommode the former.

The rich could avoid this simply by hiding their assets inside trusts or businesses that never “die” but can continue to be used by family.

It would primarily hurt the middle classes who cannot take advantage of such structures & reduce class mobility.

That point applies equally to both ‘death taxes’ and taxing bequests. Just because the solution is not perfect is no reason to reject it out of hand. But you are right that the use of trusts and other related tax-dodging schemes, that almost entirely work for the wealthy and nobody else, is another essential area for reform. The example of Liliane Bettencourt, heiress to the L’Oréal fortune and one of the world’s wealthiest individuals with a net worth of US$44.3 billion when she dies in 2017, who still paid no income tax because her income was negligible for tax assessment, illustrates the issue perfectly.

I would reject out of hand any sort of inheritance tax – however it might be structured – that was not almost entirely aimed at the top 10%, particularly the top 1%.

Similarly any income tax “reforms” should be aimed pretty much entirely at the same demographic.

Regular punters (the bottom 90%) should be fairly lightly taxed. The top 1% – and fractions thereof – should be brutally taxed, and nearly all tax reforms (and policing) should be aimed at this group.

When income tax was introduced in the UK – purely a temporary measure to pay for the Napoleonic wars, ha ha ha, – it applied only to a minority with the largest incomes. I’d like to see the tax-free threshold indexed to the median income in Australia, if not higher. It is truly ridiculous to have a system where many individuals are paying income tax while they are simultaneously eligible for welfare. The tax rates on the taxable income would then have to rise to compensate of course.

There are good reasons for supposing the tax system is deliberately made very complicated for everyone as a form of middle-class welfare or work creation for accountants. There is no practical reason why any more than a few individuals should have to complete annual tax returns if only the government felt inclined to make the required changes because the ATO has all the data it needs to issue tax assessments unaided.

But then there are universal income proposals, which tackle similar issues from a different angle.

Agreed, I have long thought all the tax brackets should be based on multipliers of the median income, with the TFT set at that – and once you get over 10x median (about the top of where you’re going to get working a job where it’s actually your labour that’s being paid for), tax should start ramping up pretty steeply.

I think for the typical joe the tax system is pretty simply – they PAYG, do a tax return once a year (probably online) and likely get a small refund.

I’m opposed to universal income, it’s just a subsidy for business. Fully onboard with a liveable and very lightly tested dole/pension though (which I typically find is what most people really want when they talk about “universal income”).

The problem with the home equity scheme is that the providers of the money charge compound interest on the ” borrowed ” money, compound interest on loaned money by the bank when it has risk etc, may be argued, although it was not in early Christianity, – it was called Usury. – for an old person’ house, already paid for and available to be seized by the banks (often somewhat unscrupulously) provides no excuse whatever for charging compound interest, I approached one of the”govt approved” organisations, – i am 73, my property assesed at $450,000, I asked if I got double the pension, (probably a more reasonable amount for most pensioners) answer, – I would lose my house in 14 years. To argue that I chose that outcome is, I suspect, incorrect, but only because of the Usury of Compound interest, – the role of the banks and their rights to make money wherever, should also be factored into any Budget deficit

scheme because there is a bunch of parasites sucking on the community teat that is skewing rational analysis.

Compound Interest should only be allowed in provable extreme risk sitchos, instead it is employed to allow thieving in any situation whatever, – an increasing the value of money without increasing it’s value crime.

According to the the government’s actuarial tables the life expectancy of an Australian male aged 73 is 13.66 years, so ‘losing’ your house after 14 years is not the end of the world. Particularly as these schemes leave you with the right of occupancy for life, so you would be able to carry on living there even if you survive to age 120. So the point remains, you can if you choose have the benefit of getting cash from your property to top up your pension if you believe you are ‘asset rich but cash flow poor’. It’s quite mad to sit in a big empty house moaning about not having cash for things when a workable solution is at hand. Why does it matter to you if your house is not your property once you die? What use is a house to you then? As the old saying goes, there are no pockets in a shroud.

These schemes just hasten the transfer of wealth and assets upwards.

The only inheritance the average punter is likely to receive is the family home and for many even that will need to be sold off to support the oldies in aged care.

Inheritance taxes should be aimed at the top few percent, where all the accumulated asset wealth is.

Just checked the suburb I grew up in, where parents bought house with War Service Home loan like almost everyone else, not a house under $1.4 million, where people have shopped locally to ensure shopping centre thrives because they remember when it wasn’t there. Likewise they built the social infrastructure for scouts, guides, life saving, sporting clubs

Ah, thems was the days.

To paraphrase or box it – “we’ve squandered our resilience/For a pocketful of mumbles/Such was neolib-promises/All lies and jest/Too many hear what they want to hear/And disregards the rest“

The Albanese govt has enough goodwill to scrap the Morrison/Frydenberg obscene Stage 3 tax cuts. Like AUKUS it was primarily created as a political wedge.

Yes…and everyone, absolutely, everyone knows this. Those who pretend otherwise are liars and hypocrites!!!

AGREE with “Those who pretend otherwise are liars and hypocrites!!!” but would add “to themselves”.

The rest of us see it plainly yet tolerate it by continuing to vote, against our own best interests, for proven failure at best and utter corruption more probably.

You’re right. But it does not matter. The Albanese government has already shown it is not interested in using any of that ‘goodwill’. It is not looking for a way out. Quite the opposite. Its objective is to prove to Liberal voters that it has what it takes to follow through on Liberal policy without flinching. Breaking an election promise would be embarrassing. The cost of saving Albanese’s blushes by implementing the stage three cuts in full is well over $250 billion, but you can be sure Albanese reckons it’s worth every dollar.

Albanese frequently promised that no Australian will be worse off. That statement was obviously made to those liberal voters you referred to because Albanese is definitely not looking after working-class Australians or those frozen out of the housing market.

“Wealth tax” and “land tax” absent, even from the “Bolder options” section.

A land tax would be for states to implement, not the federal government, AFAIK, which might explain its omission.