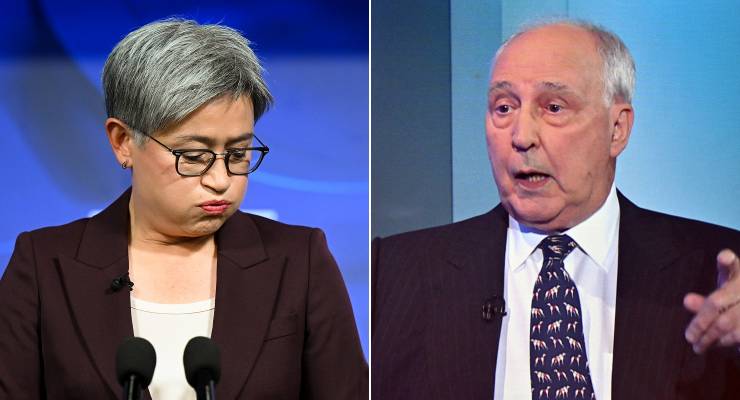

Despite the recent sparring match between former Labor prime minister Paul Keating and Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong, the two do agree on one thing: Australia’s media need to lift their game. Keating was scathing about many journalists; Wong, more diplomatically, stressed the need to “lower the heat”.

Keating’s responses to questions at his recent National Press Club talk offended many reporters, in his audience and beyond. But to those who have a growing sense of despair over what historian James Curran calls “groupthink” in our media and public commentary — on the AUKUS agreement, defence policy and talk of a China threat — watching Keating tearing into journalists must have been almost as cathartic as it was for feminists watching Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech.

But can Keating and Wong jolt journalists out of a groupthink mindset? Is a soul search by journalists likely soon?

If you look at how the media — from The Sydney Morning Herald to Sky News — reported on Wong’s National Press Club address, focusing on the personal tension between the two personalities rather than an analysis of policy differences, you realise it’s business as usual.

Why should we not expect the media to change quickly? There are several reasons.

First, as recent studies have shown, when it comes to reporting on foreign policy involving China, the Australian media are already well into a gradual but progressive paradigm shift to cold war journalism. Central to this form of reporting is what media scholars have called “cold war-mindedness”.

American media scholar Barbie Zelizer outlines a few telltale signs of such a mindset. Cold war journalism assumes the “unseen dimensions” of a war, even though that “war” may be imaginary. It also adopts a view of geopolitical reality that relies on accepting “certain strategic notions of enemy formation”. It reinforces certain understandings of who is “us” (the free world) and who is “them” (e.g. the communists). And, finally, cold war journalism reports the tension and conflict — the “imaginary war” — using black-and-white thinking, polarisation and demonisation.

There has been a gradual but certain build-up of a securitisation discourse that manifests as a China-threat narrative over the past six or seven years in Australia. The perennial tropes of invasion, threat and influence have recently culminated in speculation about an imminent war with China. In 2021, 60 Minutes warned that a war with China might be “closer than we think”. A few months later, in case viewers were not scared enough, the program broadcast another investigation, “Poking the Panda”, which warned us to “prepare for Armageddon”.

Not wanting to let the commercial media monopolise this war talk, the ABC’s Four Corners simply called its reporting “War Games”, and asked what conflict with China would mean for us. Earlier this year, a Sky News special investigation announced that “China’s aggression could start [a] new world war”.

Blaming the SMH’s “Red Alert” series for irresponsibly starting the war threat is giving journalists Peter Hartcher and Matthew Knott more credit than they’re due. The red alerts have merely served to push the persistent war refrain into a dramatic, rising crescendo.

One only has to apply each of Zelizer’s benchmarks in the analysis of these programs to see that our media are already knee-deep in a cold war mindset.

Given this, the media are unlikely to lift their game soon by giving space for “policy contestability“, by scrutinising political links to defence contracts, by getting to the bottom of what drove Wong to modify her tone on our foreign policy regarding China, or by asking whether there is a conflict of interest in Professor Peter Dean’s co-writing the Strategic Defence Review since he, as a director at the US Studies Centre, concurrently leads two US State Department-funded public diplomacy programs on the US-Australia Alliance.

But we needn’t assume the ideals of the fourth estate are dead. Instead we can see a bifurcation accommodating “watchdog” and “guard dog” models of journalism. In reporting on domestic politics, the watchdog is healthy and alert: it takes on politicians and powerful institutions. But when investigating foreign policy — on China and, to some extent, other “rough nations” such as Russia — the blinkers are on. The media reverts to guarding the interests of the security and defence establishments.

The second reason we shouldn’t expect the media to reclaim their critical role in relation to China is what has become of our media industry in an increasingly competitive digital market. Like it or not, warmongering may be a sound business strategy. In an attempt to stay afloat in a competitive sector, media organisations may simply be picking the lowest-hanging fruit by fostering talk of a possible war with China, with its sure promise of producing fear and anxiety.

Market logic may just dictate that “bad China” indeed makes good news stories. Diplomats and many industries may want to “lower the heat”, but this doesn’t make good business sense for the media.

The third reason for this pessimistic outlook is the moral psychology of individual journalists. Keating’s frustration, even anger, with journalists is understandable, but most of them are striving to do their best under serious constraints: tight timelines, limited resources, the imperative to pitch stories acceptable to editors and palatable to intended readers — not to mention working within a system that increasingly rewards prolificacy and impact (positive and negative) and discourages time-consuming and painstaking efforts to become informed and literate in areas they’re reporting on.

Moral psychologists have argued that our moral judgments arise not from reason but from gut feelings. Reason, argues social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, is important, but only because we deploy it to “help us spin, not to help us learn“. So it would be unfair to accuse most reporters of deliberately fanning anti-China paranoia. They each have personal convictions, blind spots and pride. Self-respecting journalists who invest their professional identity in certain issues such as China would naturally feel a moral compunction to defend their convictions.

In academia, a blind peer-assessment regime is meant to ensure that academics who let their gut feelings run amok don’t pass the review process. Scholars can be ruthless when reviewing the work of their colleagues.

As Haidt argues, we’re much better at spotting the flaws in others’ reasoning than in our own. But this is not how journalism operates.

Should we be afraid of China? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

One problem is that all MSM has become right wing (and by definition, pro-war) – the 9 newspapers has lost their previous progressive stance when 9 took over. The only sensible moderate journalism is now on-line, and not used yet as the reference point for political discussion.

Hartcher was a classic case of beating the war-drums early in the year.

It would be nice to see some MSM talking common sense – decrying AUKUS, tax cuts, lack of will to move jobseeker up etc.

Having visited China 10 years ago and travelled from the Vietnamese border up the East coast to Mongolia, I was blown away at how much these parts of the country had developed. For example, I travelled from near Hong Kong to Beijing in just 8 hours by train covering over 2000km.

No major country has come close to developing that fast, especially a country of over a billion people. As Paul Keeting pointed out, it seems that this war with China talk in Australia’s MSM is more about the US being outshined and not being too pleased about it rather than based in reality. It’s sour grapes and a bit pathetic really.

True to an extent but a few things to note. China’s growth was facilitated by a unique set of circumstances that are fading into history – low starting point, large growing population, low wages, Deng’s willingness to embrace market capitalism. Not saying they can’t maintain it but the middle income trap is a real problem. South Korea and Japan had an equally remarkable trajectory over the same period. Korea’s annual growth over the past 70 years is c. 6.1%, not far behind China’s 6.8%. Even Japan was averaging 9% for a long time post WW2

True enough, but China will outpace the US on many fronts (the economy and political stability for starters) for many years to come. Why are we hitching our future to a declining (and in many ways, failed) state?

Calling the US a ‘failed state’ is a wild exaggeration. The US has been rambunctious, unstable, and bitterly divided for all of its history. That is baked into the recipe for its success. And China’s top-down ‘stability’ is a double edged sword. It has arguably helps its rise but it also is maintained at considerable cost and creates fragilities of its own.

If you can’t see the writing on the wall, Paul, maybe I can ask you again in five years’ time.

In the meantime, maybe some present-day facts might help:-

disintegrating into tribalism because there is no sense of community or common identity (the very basis of a functioning society);

can’t or won’t stop their own kids from being slaughtered by gun violence;

deaths of despair in epidemic proportions;

tens of millions of people with no health care – and they actually march in the streets against any attempt to change that;

and all this in spite of being the richest society in the history of the world.

Sorry that is hyperbolic jingoism. Let’s look at some comparative figures.

China’s workplace death rate is over 6x that of the US (and that is just the data they admit publicly), which both in raw numbers and % of population towers over US workplace deaths (and in raw numbers is comparable to US gun deaths). Protests over work conditions and stolen benefits are routinely broken up by police and ‘troublemakers’ put in prison.

China’s smoking rate is over 70% among men, a fact reflected in high rates of deaths by smoking related diseases that dwarf those in the US. There is no public health campaign to reduce smoking despite the government being well aware of the problem. Cigarettes are dirt cheap and the government is dependent on tobacco taxes, which form a larger part of China’s tax revenue that income taxes. The deaths caused by not addressing this health crisis is much higher than problems caused by the US insurance system even with all its problems. (And to clarify, 30 million Americans have no health insurance, not ‘no healthcare’. US hospital emergency rooms are required to treat everyone insured or otherwise. The bigger issue is that people are heath related bankruptcies and inadequate healthcare)

I could go on but you get the picture. We can all play this game. I have lived and worked in China. I graduated from a university there. I love the country. I speak Mandarin. I have also lived in the US on both the east and west coasts. I’m well versed in the faults, fragilities, and corruption in both countries. China is no more guaranteed to rise than the US is to fall. And it would be naive to think China will be the first great power to yield its power wisely. Australia needs to stake out an independent position that is not beholden to either power. As I have pointed out elsewhere, reflexive pro-China jingoism at Crikey is as daft as any pro-US jingoism at Fairfax.

The US has always had huge problems, even during its rise to current power. They fought a civil war for crying out loud. They had to send in the troops to protect black kids going to white schools 60 years ago. And yet its global power grew for better or worse. Pointing out the fact it is violent and divided is no signal of its decline. Its decline, as much as it can be argued to be in one, is relative to the rapid rise of China.

‘Its decline, as much as it can be argued to be in one, is relative to the rapid rise of China’ – exactly my point.

Of course China has its social and economic faults, and of course China will use its power less than wisely. But having two bullies in the playground (that we can play off against each other, if we’re smart) is better than one unipolar hegemon unrestrained by any competition. We’re not only taking sides, but siding with the ailing bully, even though the new boy is our best trading partner. Madness.

And let’s put some historical context to the performance of the two economies. China was a backward, peasant economy ravaged by wars (Japan and civil) a mere 70 years ago. The US has been a wealthy, technologically advanced economy for well over a century, and they’ve squandered it. Much of what passes for the economy (and profits) in the US is just unproductive money shuffling and casino capitalism due to financialisation of the economy. Much of the rest is weapons expenditure, which is still three times China’s.

No-one is writing the US off as a superpower, but the BRICS nations (and others) are certainly looking for an alternative to the US ‘Rules Based Order’ (code for the US does whatever it wants unrestrained) – hence their reluctance to join the (largely Western) sanctions against Russia. The most interesting development here will be the rise of an alternative to the USD as the global exchange currency.

Not just sour grapes. The rise of a multi-polar world means the gradual end of US unipolarism, including the end of the USD as the world’s reserve currency (which has given the US enormous economic and political advantage since 1945).

https://www.beyondwasteland.net/p/riding-the-wake-of-suicide-sanctions?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

The unfortunate fact with this, is that Australia, regardless of which Party is in Government, blindly follows in America’s footsteps.

America have been increasing their rhetoric on China for a number of years now, and just slightly behind it are our Politicians, Defense, and Security Organizations, and of course the MSM.

It really does not make sense. China is our largest Trading Partner, and is also the largest provider of International Students into our Universities.

“ China is our largest Trading Partner, and is also the largest provider of International Students into our Universities.” And this is to be the total basis for our relationship with China? God help us.

So you think it does make sense to be fanning the flames of war against our biggest trading partner while simultaneously trying to repair the damage done to exports by Morrison, Dutton and a host of idiots? Doesn’t that strike you as insane?

Another manifestation of dynamics in the background?

There is messaging and talking points, from the US, when Sydney’s CIS (Koch Atlas Network inc. IPA) has promoted ‘geopolitical expert’ Mearsheimer several times; he is linked to the Charles Koch Foundation and like a former Lib PM has met with Hungarian PM ‘mini Putin’ Orban.

There was an article published in The Oz by CIS Head Tom Switzer citing Mearsheimer in ‘Vindicated: John Mearsheimer saw today’s bellicose China coming’ (29 May 2020).

However, like many on the US (supposedly) ‘libertarian’ GOP right, they are soft on Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, but strong antipathy towards not just China but also the EU and in some cases NATO?

Freedumb. Having travelled numerous times in US, China, Taiwan and others for work and pleasure, I was once asked where I would rather live. China or the USA. This made me think. In all countries I travelled in areas of various socio economic groups. In the early days Harlem with all the Blacks. Good people, to me, that is.

I answered China because I felt safer and have never encountered any of the so called loss of freedoms. Yes I do walk the streets alone and with friends and find myself in strange areas. In the US my accent was my savior and in China it was a smile.

I get so frustrated when I read the media misinformation. As mentioned on a previous occasion many of the factories in China are owned , managed, and supervised by staff from Taiwan and the Chinese labour force from the Provinces (Uighur) would not work through lunchtime (so visitors could catch a flight) without being paid overtime. Funny, sounded just like Australia.

Australians are so gullible to the rubbish printed by the MSM.

I too have lived in China, and seen it get more repressive under Xi. But my reason for not wanting to stay longer was the appalling pollution.

The Americans are writing a book about us. Gullibles travels.

Good grief, I lived in China for a decade and love the country but let’s not whitewash its problems. Speak with some Chinese human rights activists and I think you might “encounter” some of China’s “so called loss of freedoms”.

.” In reporting on domestic politics, the watchdog is healthy and alert: it takes on politicians and powerful institutions.”.

It takes them on very selectively.