The Ben Roberts-Smith judgment demands sober reflection on the ugliest aspects of humanity. Lying. Bullying. Burying evidence. Assault. Murder of unarmed civilians. Interfering with dead bodies. “Blooding”. War crimes. Analysed in excruciating detail in all 2618 paragraphs of Justice Anthony Besanko’s judgment.

And with recent revelations that more soldiers are yet to come forward while criminal investigations have stalled, this is a national conversation that’s at its beginning for Australia, not its end.

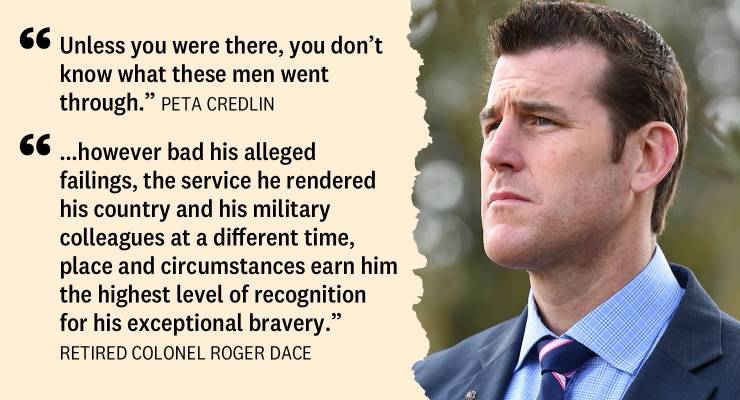

However, that conversation has instead become another culture war exercise in refusing to let disgraced heroes go, dangerously repressing that ugliness in ways that make its reemergence inevitable. We’re told that it’s just “resentment“, it’s not “the man I know”, and “terrible things happen“, while Roberts-Smith continues to be referred to as “Australia’s most decorated living soldier” and a “war hero“.

Toxic masculinity — the abusive, violent behaviour of men compelled to assert power — is normalised not only by the men who perform it, but also by those who won’t allow such men to be vulnerable, flawed or responsible for their actions.

When we deny the truth of that ugliness, and instead exhort its opposite, we assert there is no act too abhorrent for a man to commit that could prevent us from glorifying him. We pretend those horrors away without ever looking them in the eye.

Becoming enablers of toxic masculinity imbues our national character with a nature that’s at best petulant, at worst brutal. We assert with blithe arrogance that upholding one man’s reputation is more important than confronting reality.

In Roberts-Smith’s own words: “We haven’t done anything wrong, so we won’t be making any apologies.”

What’s at stake for the nation is so much more than the reputation of just one man. But Australia has long struggled with confronting violent realities.

Denying the Frontier Wars, for example, diminishes who we are and who we can become. Without the maturity to accept that this nation was founded on violence against First Nations peoples, we cannot hope to understand and redress the disadvantage faced by Indigenous communities today, let alone the meaning of sovereignty.

Similarly, denying the Holocaust and glorifying Nazis stains our global psyche and enables abhorrent behaviour. Much as we’d love to dismiss Nazis on Melbourne streets performing salutes as naïve cosplay, their terrorising intent is obvious.

Perhaps these strike you as extreme examples. However, consider what Roberts-Smith is found to have done in the defamation case. Consider also the soldiers who have yet to come forward, and the culture that normalised those actions.

Consider also the many attempts to undermine the Roberts-Smith judgment by dismissing it as just “a civil law matter” and “not a war crimes trial“. Those complaining should be reminded that this was a trial conducted at the request of Roberts-Smith who, at the time, held a leadership role in the media. While a five-year criminal investigation by the Australian Federal Police and the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions ended this week due to the risk of evidence contamination, a new specialist war crimes taskforce is continuing this work. The defamation trial outcome only adds to the many questions emerging from the Brereton inquiry.

It’s important we remember what Justice Besanko said in his judgment: that because of the conduct he has identified, Roberts-Smith now “has no reputation capable of being further harmed”.

In his first public statement after holidaying overseas on the day of the judgement, Roberts-Smith called the outcome “obviously the incorrect result”.

Refusing to accept this outcome has consequences. What’s at stake is our ability as human beings to judge atrocity and reject it at all costs — or, more crucially, even to be able to recognise it at all.

Australia has long made a national project out of how to choose our heroes. We have mythologised the Anzacs, we have invented the cultural cringe, and we have cut down the tall poppy.

A new maturity as a nation needs to emerge from this ugliness. A great deal of failure — both institutional and personal — produced Ben Roberts-Smith. We need to recognise and grapple with this. We need to make sure we’re capable of doing what it takes to prevent it from ever happening again.

This should also mean change for the media. We need to create the conditions where war crimes denial attracts the same fear as being sued for defamation.

The longer we continue to anchor our national identity on denialism, the uglier our national psyche becomes. The Ben Roberts-Smith outcome is the shock we all need to dislodge ourselves from this toxicity.

Esther writes “We need to make sure we’re capable of doing what it takes to prevent it from ever happening again.”

An obvious way to prevent future similar incidents is to tighten up the processes that govern how and when we get involved in overseas conflicts.

and we also need to tighten up the processes around who we let into our “defence” forces

Yes, but experience shows that ordinary people can be pushed into bad actions with sufficient pressure.

Indeed. Some pretty normal people did some pretty inspeakable things 80 years ago. But one example.

By what criterion?

Surely by definition, anyone wanting to don a uniform,carry a weapon and obey orders to kill people should not be allowed to wander the streets, let alone have those wishes aceeded to?

Yep, that’s the big one!

Roberts Smith now invoking the standard Trump-style denial. Everyone else is wrong.

His use of tbe royal “we” …

Him and his prosthetic drinking vessel?

What sort of person would souvenir and then drink out of a deceased prisoner’s artificial leg? One picture is worth all those words.

There are always issues around what is truth and what interpretation when things are claimed to be undeniable. I object to the use of ‘frontier wars’. It really should be settler massacres – that would be more honest and closer to real circumstances. Describing something as a war makes it seem like the people on the receiving end had some serious capacity to resist. The imbalance in weapons, power, capacity – and who the casualties were – does not support this. We do not refer to the Holocaust as ‘the jewish wars’ for obvious reasons.

On the other hand “massacre” overwrites all the evidence of genuine resistance and agency.

What do you suggest in its place? Or perhaps the indigenous community ought to be asked this question.