For 20 years, a key part of the intergenerational reports produced by governments of both persuasions has been badly wrong. And they’ve known it. Luckily, it’s proved a good kind of wrong. But examining why the best minds in the country have erred on a key policy issue might prove instructive.

Since the first one in 2002, the reports have focused on the three Ps — population, productivity and workforce participation. Treasury has got each of them wrong. The early reports badly underestimated population growth, our productivity performance fell into a hole because of WorkChoices and has never fully recovered (except for a burst under the Rudd-Gillard governments), and each report has been badly off-beam on the participation rate.

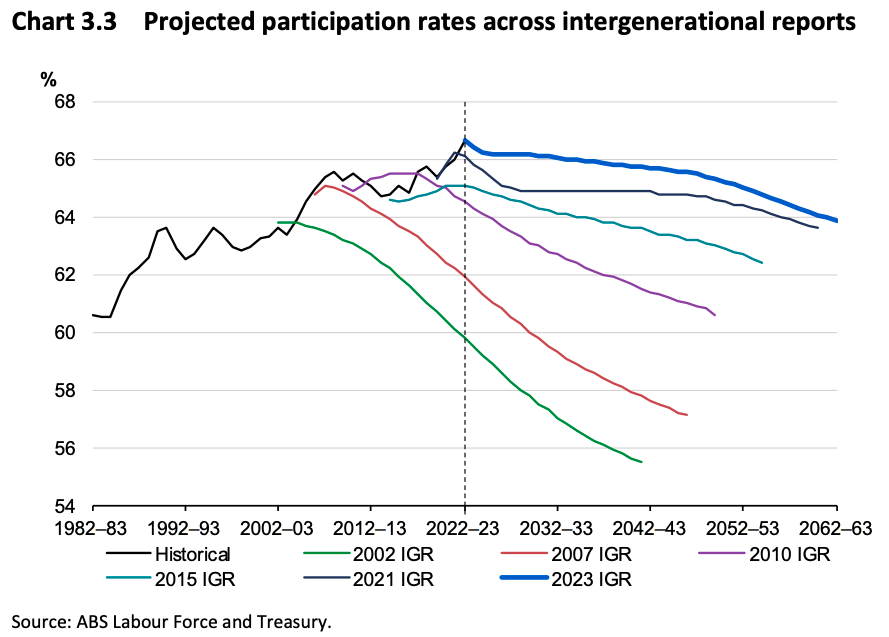

As both former treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s intergenerational report and the current one show, each report has revised up forecasts about the participation rate, meaning that there’s been a radical shift in the view of participation.

If the first report was right, the participation rate would have fallen to just 60% now; if the 2007 report was right, it would be 62%; the 2010 one (by which time the penny had started to drop that participation wasn’t going to fall off a cliff the year after the report), above 64%. Instead, it’s now 66.7%. That’s mostly been driven by the rise of female participation from below 55% in 2002 to 62.5% today.

While that long series of misses confirms that Treasury is even worse at projecting long-term trends than forecasting what will happen next year, it also means that one of the great fears that drove the original intergenerational report, that we’d run out of workers as the population aged, hasn’t come to pass — yet.

Policymakers can take some credit for this. Since 2002 they’ve sought to increase participation, mainly by enabling women to reenter the workforce after having children, or keeping women with small children linked to the job market. Childcare funding significantly increased at the turn of the century (fostering a commercial industry to exploit it, led most famously by the collapsed ABC Learning) and has steadily increased in real terms since then. Paid parental leave was introduced in 2011.

Successive governments have also used incentives for employers to take on mature-age workers, and funded training programs specifically targeted at older workers, which has, along with greater longevity, pushed older worker participation higher as well. So even as they were warning that Australia faced a participation crisis, policymakers were actually helping to fix it — something that even now they don’t fully seem to appreciate.

But bigger changes were also altering participation in ways that policymakers were oblivious to. Deteriorating housing affordability has long meant two-income households are a necessity for home ownership; as housing became more expensive and more difficult for young households to buy, they delayed having children to increase their savings, meaning more women remained in the workforce longer before having children. The proportion of women having their first child before 30 has fallen from more than 60% in 2000 to just over 47% in 2020.

But the biggest policy-driven change in participation came from an ageing population itself: in the past 20 years, increased health spending by the federal and state and territory governments has driven the health and social care workforce from below 10% of the entire workforce to 15.3% this year, making it easily the fastest growing industrial sector.

That has flowed directly into female participation, because 76.5% of the health and social care workforce is female. The huge increase in spending pumped into the sector over the past two decades has done little to de-feminise that workforce — the proportion of female employees in health and social care was less than two points higher, 78.3%, in 2002.

The drive to encourage women back into the workforce by funding childcare has had a similar effect. Childcare services — the workforce for which is also nearly 77% women — makes up the bulk of the social assistance services employment category, and that category has tripled in size since 2002 as childcare funding has driven the expansion of the sector. Female social assistance workers made up less than 2% of the entire workforce in 2002, but now make up over 4%. They are a bigger workforce by themselves than financial services, agriculture or mining (in fact they’re almost as large as those two combined).

As with every other intergenerational report, last week’s predicts that participation is about to peak and will start falling — less precipitately than previous reports, but with increasing speed over the coming decades. And, surely, they must be right this time? Participation can’t go on rising forever, can it?

Except the big factors that have driven increasing female participation are not merely remaining in place, but increasing. Health and especially aged care funding are set to continue to grow much faster than GDP, along with the NDIS, another subsector dominated by women. The ongoing decline in housing affordability will continue to force women to delay childbearing, and discourage some couples from having any children. And we’re continuing to increase funding for childcare, and increasing investment in early childhood education.

Many of the women who will do these caring jobs will come from overseas. But given each intergenerational report has got participation so wrong, who’s to say this one will turn out to be right?

Do you think that workforce participation will continue to increase? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

as John Quiggin says at the end of his piece on the Intergenerational Report in The Conversation :

As it happens, we are facing a catastrophe, and it has scarcely been mentioned in the five intergenerational reports to date. It’s catastrophic climate change. … In these circumstances, worrying about the need to raise taxes by a few percentage points over 40 years to pay for things like more aged care shows an astonishing lack of concern about the future.

https://theconversation.com/the-intergenerational-report-tries-to-scare-us-about-ageing-its-an-old-fear-and-wrong-212003

Hi! Roberto.

I totally agree with you.

it is interesting that the Climate Catastrophe never gets a mention,other than perhaps an offhand comment in just about any report or forecast in this type.

This only reinforces my belief that the general output of reports by Business, Government Etc., is to convey the impression that everything is fine, under control and normal. That is “just keep the Peasants calm”.

The report also does not mention the effect of Artificial Intelligence and it’s developments.

Taken realistically, what current jobs can not be done by A.I.? Think it through, the only major employment will be in service jobs like Nursing, maintenance, policing, and jobs requiring random ad-hoc human intervention. Anything programmable or knowledge based, Teachers, Lawyers, Doctors, shrinks, and so on can be done better by A.I.

But our puny Pollies think they can forcast 40 years ahead and determine, then, by what is happening now (skipping a few inconvenient facts). ROL.

One, like others, interpreted his views differently, i.e. claims that the IG was ‘ageist’, but like the preface to this piece

‘Intergenerational reports have always warned we’re going to run out of workers. They’ve always been wrong.’ Ignore the future at your peril.

Bypasses the phenomenon that hath no name, better health, increasing longevity and a baby boomer bomb/bubble moving into retirement, i.e. one of the most significant changes to Australia impacting taxes, budgets, services, infrastructure etc. for the next generation; not a crisis but very manageable.

OECD data is stark, whether one looks at fewer youth, working age is stagnant approaching decline (numbers are kept up by students etc. counted into the EstResPop via NOM) vs. growth in old age dependency ratios due to baby boomers.

https://data.oecd.org/chart/7ayo OECD (2023), Old-age dependency ratio (indicator). doi: 10.1787/e0255c98-en (Accessed on 28 August 2023)

I suspect a great deal of increased female participation over the last decade or so is driven by the increasing need for multiple incomes to pay for rising prices of essentials like housing (be it purchased or rented). It kicked off at roughly the same time as the present-day bubble.

Undoubtedly the same people worried about sufficient labour participation are also wondering why we aren’t having as many (/enough) babies.

Australia’s high-volume, low-skill immigration programme is also another significant factor suppressing productivity. No need for employers to automate and/or increase efficiency when there’s an endless supply of cheap, easily exploited labour on tap !

That’s linked to “inflation” as well.

Just as us plonkers aren’t getting as much “bang for our buck”, so too “we are no longer getting as much “bang for our …..”

Yet again the ignored elephant in the room that Crikey stubbornly refuses to acknowledge.

The environment is another cause. Many young people ask themselves ” is it fair to bring a child into a world that is heading for disaster”. The answer is often “no”.

I am fearful myself about what the youngsters of today including my own children will be faced with starting with this next summer.

The primary reason why I’ve never donated my sperm to lesbian friends when asked in the past. It was clear to me as a teen in the late 80s that contributing to (global) exponential population growth was a bad idea.

“Think fossil fuel world…. Just keep doing the same thing over and over and over, and expect a different result.”

Ah! The charming human delusion that we can predict the future, and based on that fallacy, we can plan it in detail. That is the utter nonsense to which government is held accountable. Instead, make policy on current evidence: do more of what evidently does good, and do less of what does wrong. Stay flexible. When new evidence emerges, adjust the good/bad compass. Stop wasting so much time and money unsuccessfully attempting to predict the future.