Proposed legislation on media freedom has been met with enthusiasm by government MPs amid a host of high-profile defamation cases clogging up the courts, declining trust in media and journalists, and increased scrutiny on the Albanese administration over transparency.

A “Media Freedom Act” has been proposed by the non-profit Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom (AJF). According to the AJF, since 9/11, Australia has produced more national security legislation than any other country in the world (more than 90 separate laws). The AJF argues that given Australia don’t have any constitutional protection for press freedom, many of those laws limit journalists’ ability to investigate the government and protect their sources.

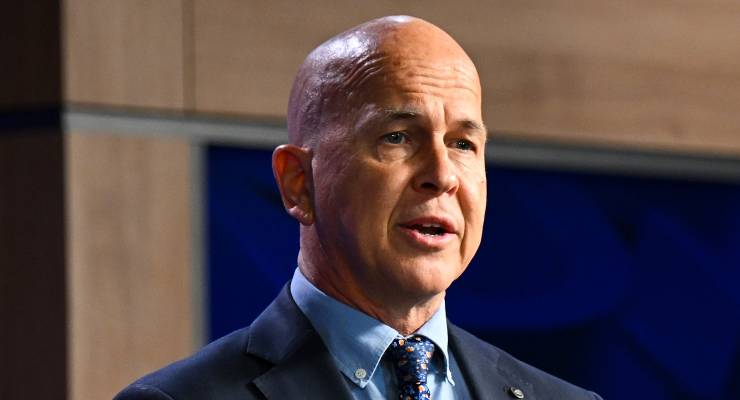

The AJF was founded by Al Jazeera journalist Peter Greste, who rose to prominence in 2013 after being arrested on “national security” grounds while working in Egypt. He was accused of being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and spent 400 days in prison before eventually being returned to Australia after intervention by the Australian government.

“When I was in Egypt, I really thought long and hard about what had happened to us and realised that it was about what we’ve come to represent,” Greste told Crikey.

“The war on terror has created a war, not over tangible things, but a war over ideas. In that war of ideas, the space where ideas are transmitted becomes a part of the battlefield. We were literally victims of that approach.

“9/11 gave governments the world over the opportunity to pass loosely framed national security legislation that was then used to come after uncomfortable journalism.

“[In Australia], the data retention legislation is a good example. We know that [it] gives the intelligence agencies the ability to look into any Australian’s metadata without a warrant — the journalist [exceptions] were only added after the media screamed long and loud about it … but we know from a number of parliamentary inquiries that police have, in fact, investigated journalists’ data without a warrant.”

Sources familiar with the discussions told Crikey a number of MPs from across the aisle had been approached by the AJF in recent weeks in preliminary conversations seeking to secure in-principle support for an eventual media freedom act. Crossbench independent Zoe Daniel was said to have been supportive, while the chair of the parliamentary joint committee on intelligence and security, Labor MP Peter Khalil, was said to have been “very enthusiastic”.

Sources told Crikey that Khalil offered to organise meetings with a number of other MPs, including the attorney-general, although it is understood that these meetings are yet to take place.

Daniel’s office confirmed the meeting when asked by Crikey, as did Khalil’s.

A spokesperson for the attorney-general told Crikey the government had “already introduced a number of important measures to improve protections for press freedom, and is continuing to consult with media representatives on further measures to implement … recommendations made by the parliamentary joint committee on intelligence and security”.

While politicians were not presented with a concrete proposal, a draft act seen by Crikey would seek to put explicit obligations in place to consider media freedom when passing new laws and interpreting existing ones.

It would require an “impact report” to be tabled alongside proposed legislation that would explain how the legislation would avoid unnecessarily limiting media freedom, and in the event that this would be unavoidable, explain why there was an overriding public interest in the restriction.

The proposed act would also seek to categorise journalism as a process that is accountable to a recognised code of conduct or set of professional standards, and implement a “rebuttable presumption” that work done in the course of journalism deserves additional protection under the law.

The AJF has also raised, alongside the proposed act, the idea of a voluntary professional association that enforced journalistic standards through a complaints mechanism, and certified members with a badge next to bylines.

Greste said the proposed act was only one part of a bigger picture when it came to media freedom, but stressed that it was early days, with the only discussions with politicians being “preliminary”.

“The media freedom act is just one part of it — we think that the professional association [proposal] is an important part of this,” he said.

“We think that part of the problem with misinformation and disinformation is that a lot of not-journalism looks pretty much the same as good journalism. There’s just no way for the public to distinguish between the two.”

Asked whether the establishment of a voluntary professional association would impede on the role of the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA), the responsible union for journalists with its own code of conduct, Greste said that the primary objectives of the union differed from a proposed voluntary association.

“The union’s primary objective is to represent the interests of its members in industrial disputes. I appreciate the union has its code of conduct and has its ethics committee … [but] we think that there’s a need for a more robust way of … specifically upholding professional ethics and standards.”

Greste said that there is already an issue in Australia with the media industry’s “problem of public trust and public ethics”, underscored by the latest revelations in the Bruce Lehrmann defamation saga.

“If we want a media freedom act, we also need the social licence to operate — we need public confidence. If we set up a professional association that takes a process-based definition as the basis for membership, we think that then provides a better way of providing industry self-regulation.”

It is understood that there is a concern, particularly from Coalition MPs, about the potential impact such a proposal might have on national security. But despite the next election looming and the Albanese government struggling in opinion polls, Greste said he wasn’t concerned about a change in the flavour of the government.

“Politicians often talk about striking the balance between press freedom and national security — we think that the word ‘balance’ implies a false binary. It implies that if you have more of one, by definition, you have to have less of the other. We don’t think that’s an accurate way of describing it — we think that press freedom is a part of national security in the sense that its an essential element that keeps the system functioning and healthy.”

In any case, Greste said he hoped the proposal would “appeal to all sides of the House”.

“We think it supports conservative ideas around transparency and accountability of government and freedom of speech and freedom of the press. We also think those ideas sit very squarely within the Labor Party. In the conversations we’ve had with crossbenchers … they also recognised the importance of media freedom and acknowledged the fact that it’s been undermined by a lot of the national security legislation that’s been passed.”

Disclosure: In 2023, after receiving $1.3 million from Lachlan Murdoch as part of the settlement of his defamation claim against this masthead, Crikey’s parent company Private Media donated $588,735 raised in crowdfunding for legal costs to the Alliance for Journalists’ Freedom as a condition of the settlement.

He conservatives would be concerned that they might get caught out. With good reason.

Conservative values, freedom of the press, speech etc! What a load of bullshit!