We are the co-authors of a study published today in the Medical Journal of Australia, which shows that the federal government’s income management policy is not making an impact on tobacco and health food sales in remote community shops in the NT. Smoking and poor diet are responsible for much of the health gap between indigenous and other Australians.

We are concerned that indigenous affairs minister Jenny Macklin has responded to our study by highlighting the results of the government’s evaluation. She has told journalists that the government intends to press ahead with plans to roll out income management more broadly, and has appeared to dismiss our findings.

The evaluation cited by the minister was based on interviews with 76 income management clients in four communities, telephone interviews with 66 store operators as well as interviews with business managers and other stakeholders across several locations.

This is poor use of qualitative research to answer a question that essentially requires quantitative data: are people buying more healthy food as a result of income management?

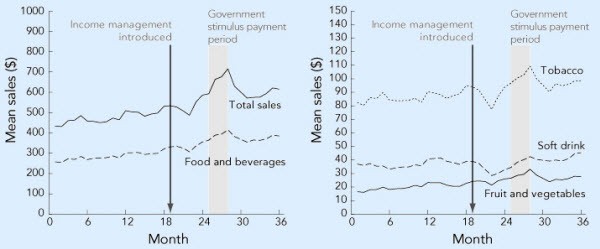

Our study provides that quantitative data. It used sales data to measure how much was being spent each month across 10 stores in the Northern Territory, 18 months before and 18 months after income management was introduced. In contrast, the government’s evaluation report of income management and spending relied entirely on people’s perceptions in a large number of interviews.

We confirm store managers’ claims that there was no change in people’s spending on tobacco.

However, in contrast to the government report, we found that spending on food and drinks and fruit and vegetables did not change with income management. Soft drinks sales increased.

The one time during income management that spending went up for all store commodities was when people actually had more money: at the time of the government stimulus payment.

Telling people of low income how they can use 50% of their income may make no difference to their spending, but giving a lump of cash does.

(Source: Medical Journal of Australia — click to enlarge)

The government’s evaluation report claims that “the main benefit identified [of income management] was the increase in the amount of money spent on food for community members, especially children”. This is now questioned by our evidence.

Even its minor claims of improved food choices, more fresh and more healthy food being purchased, are linked to the new licensing of stores in these communities — not income management.

Continued income management in remote NT Aboriginal communities and its extension to all welfare recipients does not seem to fit with the government’s credo of evidence-based policy.

Whilst the government’s defence of income management with only very shaky evidence has been controversial, gaining little support from public health experts, it has received applause for its work on prevention, and smoking in particular.

It has allocated $100 million to indigenous tobacco control, using the limited local indigenous research but extensive international evidence from other contexts. Its recent decisions to increase the tax on cigarettes and to restrict tobacco companies’ advertising using cigarette packets are also likely to reduce indigenous smoking.

But attempts to tackle indigenous people’s poor diet have not been as coherent and are off to a shaky start. There is no funding for either the COAG food security initiative or the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nutrition Strategy and Action Plan. The government is yet to respond to the 33 recommendations of the Senate inquiry into remote community stores.

But store licensing, which is setting minimal standards in remote stores in the NT, and the funding of 100 new indigenous healthy lifestyle workers are welcome and positive steps.

Less welcome is the reluctance to consider food subsidies. Yes, they are expensive and difficult to monitor, but there is increasing international evidence that modifying price and monetary benefits, such as food stamps, help to improve the diet of economically disadvantaged groups.

As Amanda Lee and colleagues have stated, we need rigorous testing of economic solutions to increase access to healthy food in remote communities.

Skirting the real issue of affordability and poverty, while defending and extending income management policies, may delay improvements in indigenous people’s poor diet and the government’s pledge to “close the gap”.

*Dr Julie Brimblecombe and Associate Professor David Thomas are from the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin

I become almost furious when the Government deliberately tries to mislead the public regarding the “success” of its programs which purport to help Aboriginal people. Intuitively, even without the evidence shown here, income protection and other paternalistic programs can not work for the simple reason that such things are the cause of many of their problems in the first place. This is further evidence that nothing has changed since the 1700’s, and further evidence that nothing will change. The Government’s catchphrase “Closing the gap” is, putting it bluntly, a lie when it has no intention of doing so.

I have carefully read the Brimblecombe et al. piece in MJA ‘Impact of income management on store sales in the Northern Territory’ and find it the most comprehensive and scholarly quantitative research available to date on the food and tobacco expenditure impacts of income quarantining before and after the Intervention. As Brimblecombe and Thomas point out in Crikey today it is quite inappropriate to compare this research undertaken by academic experts at arms-length from government from research undertaken by federal bureaucrats or their paid consultants; and to compare rigorous quantitative research that addresses a specific question of sales before and after income quarantining with qualitative research that asks general questions about expenditures on broad categories of goods in government-licenced stores post Intervention only. The Australian government is clearly embarrassed by these research findings for three reasons. First, $82.8 million have just been committed in the 2010/11 Budget to create a new scheme for income management, an investment in a process to regulate the behaviour of welfare recipients in the NT. All up $410.5 million will be committed in six years to what might prove an entirely unproductive expenditure. Second, legislation is about to be tabled in the federal parliament predicated on an assumption that income management is good for Indigenous (and other) subjects in the NT, something this research seriously questions. Third, the Rudd government has remained firmly wedded to this intervention measure since its election in November 2007; saying sorry for others ‘historical’ errors is clearly politically easier than saying sorry for your own ‘path dependent’ acquiescence and possible mistakes.

Ten Stores out of 100 or more – is that a conclusive quantitative study. Which stores and where????

How about taking in clothing for kids, health products and household items as well. These are just as important as food in the “quality of life” debate.

One wonders whether these people, including Altman spend much if any time observing the actual issues that are clearly being addressed in these communities, and the income management programme is a vital part of the formula.

Of course there would be little change in tobacco purchases – the price goes up all the time, so consumption may be falling. Who knows??

An excellent report (in a great edition of eMJA) and a good article. I agree with Jon’s comments.

For anyone worried by the NATIONAL income management legislation currently before the Senate, you have 4 weeks to do something about it. We’ve had a reprieve – as the legislation was listed to go through the Senate (with the support of both major parties) last Wednesday but is now likely to come back in the week of 15th June.

The thing that worries me is that this scheme has been so expensive to administer in the NT so far – rolling it out further in the NT or into other states will pull significant resources out of other social services which actually have a proven track record. Without putting major resources into financial counselling, case management, rehab and referral programs … and with there being no path ‘up and out’ of IM in the legislation it is just a recipe for making peoples lives much more miserable and producing far worse outcomes … particularly for disadvantaged people who are doing the right thing in caring for their kids and looking after their meagre incomes and are indiscriminately impacted by these silly laws.

There is some more information and an action pack on Senator Rachel Siewert’s website at http://rachelsiewert.org.au/im

Graeme, I would have though that the behaviour in ten percent of stores would provide a sizeable sample of overall activity. Are you basing your comments about ‘actual issues’ and IM being a ‘vital part of the formula’ on a larger sample than ten stores?

If you’ve also done some sound research work can you please share it with us?

I should also point out the only place ‘conclusive’ appears is in your comments. The point was that the evidence of the study was of a higher quality that put forward by the Government.