As the chorus of criticism surrounding the federal government’s proposed Resources Super Profit Tax continues to reach a powerful crescendo, perhaps it is also worth paying attention to the major area in which the revenue would be used. That is a reduction in the company tax rate.

While few experts and mining figures believe the present royalty system is working well, even fewer agree that the government and treasury’s solution to the problem is remotely a good idea.

There are five pretty glaring reasons why the RSPT was a poorly thought through policy.

First, there is apparent confusion at government levels about the concept of a business’ cost of capital (given the rate at which the super profits tax kicks is critical, one would have through that someone at treasury would have bothered to open a first-year business finance textbook). Second, there is the bizarre “refund” mechanism, which may end up costing taxpayers billions, and that the miners don’t want anyway because an illusory refund doesn’t help them finance new projects. (The RSPT effectively forces taxpayers to invest in mining projects that they would have no interest in and forces mining companies to accept this investment which they do not want).

Third is the substantial risk that otherwise viable projects will no longer proceed because the government has created a massive distortion to the market (Alan Kohler noted in Business Spectator today that a KMPG report found “the application of the RSPT results in negative net present values for nickel, copper and gold mines, and it reduces the NPV for iron ore and coal projects by 46% and 57% respectively.”

Fourth is the probability that a Chinese slowdown may weaken commodity demand, meaning that it is not unthinkable that the tax will raise no where near the revenue the government and treasury are predicting (and worsening the “refund risk” mentioned above). Finally, there is the fact that mining companies pay a fair bit of tax at the moment — BHP paid an average tax rate of 30% between 2004 and 2009, compared with only 18% for Wayne Swan’s good friends at Macquarie Bank. So it seems strange that Rudd and Swan are placing a super tax on fairly taxed miners, while at the same time offering billions of dollars in taxpayer funded guarantees to the tax-minimising Macquarie.

The main argument proffered by the government in its botched attempt to sell the RSPT is that mining companies (especially the likes of BHP and Rio) are largely foreign-owned anyway, so the super-profit tax will mainly affect non-Australian shareholders. Leaving aside the sovereign risk attaching to such a decision, politically speaking, the government makes a reasonably good point. So what if the dividends paid to a bunch of American institutions are reduced — so long as we can use the money to build an overpriced and unnecessary broadband network for rural Australia?

However, that argument is rendered meaningless when you look at what the government plans to do with the super tax revenues.

According to the Future Tax website , the government will use the revenues from the RSPT to “reduce the company tax rate to 29 per cent for the 2013/14 income year and to 28 per cent from the 2014/15 income year”.

A reduction in the company tax rate will allegedly have several benefits, including:

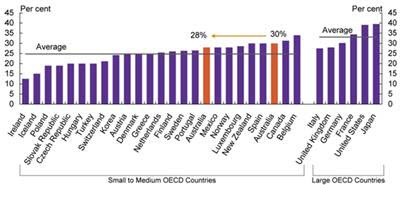

[Improving] the international competitiveness of Australia’s company tax rate, moving Australia from 22nd to 17th among similar-sized OECD countries. Presently, Australia’s company tax rate is high relative to other similar-sized OECD countries.

By reducing [the company tax rate] we can reinforce that Australia is a good place to invest. Over time, this will lead to an increase in investment, particularly from overseas. Increased investment means a larger capital stock, higher productivity and higher wages. More investment will also mean more innovation and entrepreneurial activity.

So on one hand, the government is creating a new big tax (the RSPT) that will discourage investment, only to give that money back by reducing the company tax rate on the basis that it will encourage investment.

Australia already has a lower company tax rate than the United States and Japan (see graphic below). And even more ironically, the only real winners from a reduction in the company tax rate are foreign investors. Most local shareholders, especially those who own small and medium-sized businesses, need to pay dividends/salaries to owners anyway. These payments are taxed on an individual basis at the recipient’s marginal tax rate. Presently, with dividend imputation, the company tax rate is almost irrelevant to Australian shareholders (with the exception of timing benefits).

Source: Australia Government Future Tax website

So to clarify, the government is taxing an industry on the basis that it is owned by foreigners, and using those revenues to reduce the amount of tax paid by other foreigner investors. All the while distorting investment away from a productive industry (mining) into all other sectors of the economy. Meanwhile, Rudd is back-tracking on election promises and using taxpayer money to sell the entire fiasco.

Does Bernard Keane never read this far down the Crikey e-mail?

Adam,

I think you’re spending too much time with the Business Spectator folks, who for whatever vested interest reasons are going all guns blazing against the RSPT, but seem to not really be too engaged with the actual debate.

So to clarify, the government is taxing an industry that suffers from a greater boom-bust cycle than the rest of the economy in such a way that more revenue is generated for the Australian government during boom times, but also so that the fixed costs of royalties are removed during busts, resulting in a more stable, less cyclical industry, putting less pressure on the rest (92%) of the economy. If some steam is taken out of the industry during boom times that should allow the macro economic policy interventions via interest rates etc to be less extreme.

Does 100% of company profit go to investors? No, it doesn’t. Profit is also used to grow businesses, so reducing company tax will leave more funds for growing existing businesses across the whole economy, again that’s 92% of GDP not in the mining industry.

The rate at which the super profits tax kicks in does not, as far as I can tell, have anything to do with business cost of capital. This, to me, sounds like a confusion on your part of the difference between profit and return on investment. Given that the ‘model’ for the RSPT is that of a 40% partnership, a real 40% joint venture wouldn’t have a threshold of any sort – 40% of costs and 40% of ALL profits, not just those above a threshold, would be passed to the minor partner. As I see it the 6% threshold is an additional fillip for the miners and is intended simply to make it so that stopping production and putting cash in the bank is not more tax effective.

You’ve also fallen for the line that because the ‘refund’ may not help the miners get finance immediately means that it has zero value. I think this is the area that could have been most influenced by genuine good-faith discussions between the miners and the government in terms of making the refund actually tangible for finance, because it should be (see Ross Garnaut’s comments to this effect in his interview with Alan Kohler). However, even if the refund mechanism is not usable directly for finance, it STILL provides a reduction in downside risk for the miners; perhaps not valuable at 100%, but certainly not zero value.

Regardless, I would recommend you stay away from the koolade.

Having read this article and that the response from Jackol above, this is the sort of responsible analysis, although I would prefer a less of on of Jackol ‘s sarcasm and a little more constructive analysis.

I would have expected to see this type of analysis and counter analysis as part of a carefully thought through position paper on this whole subject to be presented to the Australian community with the Budget, together with a reasonable summation of the potential outcomes (both positive and negative across) different sections of the community so that we can have an informed discussion on the subject which is of great importance to the country as a whole.

The abject failure of the government to treat this subject seriously, and to use cheap throwaway lines as a substitute forfor constructive analysis needs to be sheeted home to Rudd and Swan. As community leaders they have failed dismally to communicate the underlying basis of this strategy with a clear delineation of the impact on each sector of the Australian community, underpinned by reasonable quanitative analysis.

I am reminded of the old riddle as to the difference between a used-car salesman and a computer salesman. The answer was that the used-car salesman knows he is lying. I think we have a similar problem with the politicians except that in this case I am not sure whether the politicians know that they are lying or not. This does nothing to inspire confidence in our leaders.