So who was the first-term prime minister who saw his strong polling position turn into deep electoral discontent despite handling an unexpected crisis adeptly, amid criticisms of his leadership style, the defection of part of his political base to a minor party and speculation about an ambitious deputy?

Well done those of you who said John Howard.

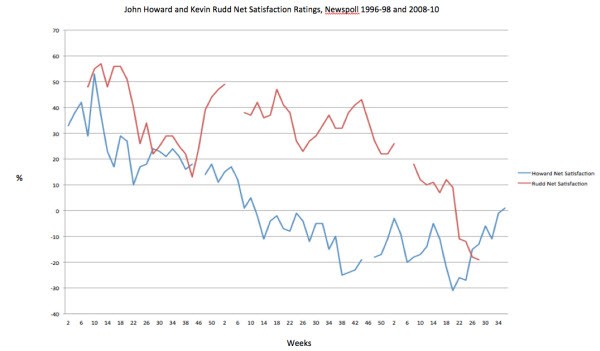

If you want collapses in voter confidence in first-term governments, Kevin Rudd had nothing on Howard. Newspoll shows Howard started with the same stratospheric polling ratings as his successor, and briefly had a net satisfaction rating of over 50 percentage points in the wake of his handling of the Port Arthur massacre. He rapidly declined after that, though, and by May 1997 had the first of what would become a great many negative satisfaction ratings.

Rudd, too, began very high and then declined — but his well-handled crisis came later than Howard’s, who had to deal with Port Arthur and the gun laws issue only weeks into his prime ministership. It was Rudd’s handling of the GFC, and in particular his second stimulus package, that reinflated his net satisfaction rating back over 40%. It stayed in the 20s and 30s and then went back up over 40 points again as Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership went into meltdown. After that, Rudd fell back to earth with a thud, every bit as quickly as Howard originally had.

The only difference in that fall was Rudd never plumbed anything like the depths that Howard reached. At about the same stage as the equivalent point in Rudd’s term that the latter, for the first time, slipped into negative net satisfaction, Howard hit his nadir — a minus 31 point net satisfaction rating. That was in late June 2008. It wasn’t until the very eve of the 1998 election that Howard struggled back into positive net satisfaction territory.

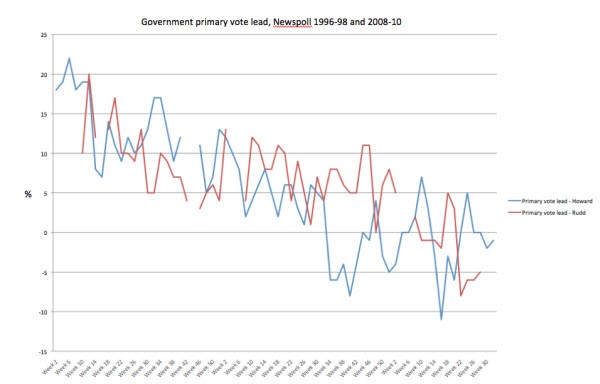

The Liberals’ primary vote matched a similar, though less spectacular, trajectory under Howard. At one stage, a few weeks after Howard’s defeat of the Keating government, the Liberals held a 22-point primary vote lead over Labor, 55-33. But by late 1997 the Coalition had fallen behind Labor.

By that stage, Kim Beazley was routinely besting Howard as preferred prime minister. The Coalition went ahead again in early 1998 but then fell behind again as the year went on (and Howard similarly overtook Beazley as preferred PM but then fell behind). In June 1998, the Coalition trailed Labor by 11 points on the primary vote as One Nation and the native title debate reduced their vote to 34%. They didn’t even match Labor’s primary vote at the October 3 election.

Under Rudd, Labor played out a similar trajectory, but again, never as dramatically as the Coalition under Howard. In fact if the Liberals had offed Howard at the same time as Labor got rid of Rudd, Howard wouldn’t have made it to December 1997. Labor only went properly into negative territory on the primary vote in late April after Rudd’s ETS decision, which sent Labor’s primary vote 8 points behind the Coalition. Since then, however, it has been slowly recovering.

And Tony Abbott never got within cooee of Rudd as preferred PM.

In fact, Rudd lost his first three preferred PM polls to Howard (by three, two and one points respectively) but thereafter was never headed on that metric. Howard got within one point of Rudd in July 2007, prompting historic levels of Shanahanigans, but Rudd kept his record intact all the way until he was taken out and shot by ALP powerbrokers.

What to make of all that? Well, in practice, nothing because he’s finished, and Julia Gillard is PM. And perhaps you could argue that Rudd only ever polled so well because the Liberals constantly found ways to distract voters and the media from focussing on his shortcomings. Whether it was Howard versus Costello, Nelson versus Turnbull, Costello versus Turnbull or Abbott versus Turnbull, for three years the Coalition was a constant source of leadership speculation and destabilisation, which only ended when his party locked in behind Abbott in December. Howard, in contrast, was up against a united Labor locked in behind a well-regarded, experienced leader in Beazley.

But it does suggest all but the most easily-panicked Labor MPs knew, or should have known, that they could win with Rudd, reinforcing the idea that it was Rudd’s chaotic and alienating management style that was the true cause of his downfall.

It also says this: being an effective prime minister — or at least one determined to achieve real change — is hard, and takes practice. Howard handled the gun laws issue strongly and courageously, and with Costello wrestled the Budget deficit back under control without alienating voters. But he badly botched native title — admittedly sprung on him by the High Court with the Wik judgment in December 1996 — and the waterfront dispute was so poorly handled it actually engendered sympathy for one of the most bloody-minded unions in the country. Moreover, in response to the rise of One Nation, Howard stranded himself between a policy of appeasement and the hardline assault on Hanson favoured by Costello and Abbott.

In all cases, Howard’s communication skills, or lack thereof, were a key problem.

Rudd botched a number of issues, and was far more risk-averse than his predecessor, and made Howard look an orator of Lincolnian eloquence. But he appeared to have belatedly worked out that you don’t get anywhere by caving in to vested interests like Telstra and the mining companies. He too might have grown into the role after surviving a scare in his first effort at re-election. The result might have been a more mature, more effective reformer.

Instead we’ve got Gillard, who is walking as fast as she can away from anything faintly controversial in the Rudd legacy.

You can draw your own conclusions about which side of politics is more prepared to back their prime minister when the chips are down.

Howard nailed the essential difference between them himself when he said that love him or loathe him, people knew what he stood for. Rudd confused everyone with the disconnect between his overblown moralist rhetoric and his contradictory actions and sometimes inaction, on key policy areas.

Howard did not really fatally lose the trust of the electorate until his fourth term, whereas Rudd had clearly lost it by last week. Once lost, it would never be regained.

The other essential distinction is that rightly or wrongly, Rudd was perceived by people almost as their president, given the manner of his campaign and subsequent election. (He certainly acted in a more presidential way than any previous Australian PM). This view has been validated by the outcry against the PM “elected by the people” being replaced by someone installed by faceless men etc. This being the case, his failings were taken more personally by voters and therefore were more difficult to address when the polling went south.

The events of last week are an interesting view into the contradictions of the emerging tendency towards presidential style campaigning in Australia, and the realities of the Westminster system we actually have. If it means more interest being taken by more people in how we are governed, that will be a good thing.

Yeah but a major factor in the panic by the labour party was a quite extraordinary campaign of assassination by the media. Rudd deserved to be criticised over his lack of courage on ets in particular and falling for the fear campaign on refugees but there was no objective balance in the reporting. Particularly the oz had quite a vindictive and agenda laden campaign. I don’t recall howard facing such a one sided campaign. The oz was (and still is) as close to a liberal party brochure as you can get with really just token critiquing of the coalition. Its a shame because there is intelligence and policy detail there but unfortunately it is misused.

And when the Oz does criticise the Coalition, Jeremy, it’s in the voice of a cheerleader or coach, always looking for the best spin or advice to win the match for the home team.

@ Jeremy,

I completely agree. I can’t remember such a vicious, sustained attack on a PM. With the party never a serious chance to lose the next election, this decision is unfathomable. It’s also one that will come back to haunt them all. Gillard will pay a high price for this and Abbott’s already running the very good line that the ALP knew it was going to lose, so it panicked.

It’s a pretty persuasive argument and it’ll only get stronger if Gillard (as Bernard noted) keeps on walking away from controversial decisions.

Michael

PS Media complicity: where was the coverage on maternity leave? This is a major reform but you’d hardly be aware of it if all you had to go on was the mainstream press.

PPS Lucky for the Coalition that Turnbull has decided to stick around – he’s the only one who has the wit to take the fight to Gillard.

I’ve been hearing about “presidential style” politics in Australia for nearly 20 years now. Keating was said to be a Prez Stylez PM. Howard was hardly a consensus style PM either.

While its common knowledge that the ALP won more votes in the 1998 election they did poorly in the marginals and thats where Howard won. I think this is where the factional leaders panicked and feared a repeat of 1998. Losing primary votes to the greens in urban, inner city electorates isnt that big a worry because you know the two party preferred will still flow to Labor.

But out in the regional, semi-rural and outskirts voting Green is about as socially acceptable as torturing and killing kittens and puppies. There will be no flow on from preferences from the Greens out in the out Western Suburbs of Sydney. The ALP needs a high primary vote in these areas. It doesn’t matter how big you win in your safe seats, each electorate is only one seat in the House of Reps.