Since Qantas insists on departing from the normal ways of reporting financial results and using its house rules for “underlying profitability” instead, it is reasonable to describe this morning’s full-year results as that of an airline shafted by the light.

The result of an underlying profit before tax, let’s call it a UPBT, of $377 million in the 12 months to June 30 is a ripper, and but for the wrath of an Icelandic volcano in April, would have been a UPBT of $423 million, more quadrupling its UPBT of $100 million in FY ’09.

But in the second half of FY ’10, Qantas only made UPBT of $17 million from actually flying, that is Qantas (domestic and international) made only $7 million UPBT in the past six months of the year, with a fleet of more than 100 jets compared to $60 million UPBT in the first half, and Jetstar, which is where the money seems to be these days, made only $10 million UPBT (but with a fraction of the Qantas fleet) in the same period, compared to $121 million UPBT in the previous six months.

Now we know why former Qantas executive general manager John Borghetti hit the profit downgrade button so hard at Virgin Blue soon after occupying the CEO big chair in May. Things changed, for the worse, very quickly, and Qantas Group CEO Alan Joyce made numerous references this morning to how “leisure demand softened” in the last quarter of FY ’10.

Confused? Before the UPBT metric was invented by the Qantas after the departure of Geoff Dixon as CEO nearly two years ago, Qantas made $1.408 billion in old-fashioned PBT, fortuitously before the fuel price crisis was fixed by the much more damaging impact of the GFC.

There is no arguing that the new metric is used with very good reasons by Qantas, and also Virgin Blue, to remove ineffective fuel hedge values and other non-cash variables, but it can cause confusion especially when comparing the good times to the present “challenging” times.

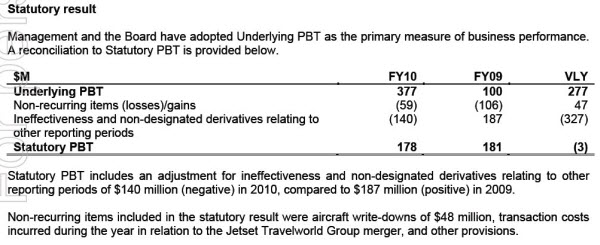

This is the actual summary of the past two full years of Qantas statutory earnings as posted on the ASX this morning.

Note that the Qantas group thus made $3 million less than it did in FY ’09 on a statutory PBT basis, and far less than it did in FY ’08, but for reasons that do not reflect adversely on the present management.

But what today’s results do make clear is that selling Qantas points to non-flyers such as credit card services, Woolworths and other retailers to use as merchant inducements is far more profitable for Qantas than flying people around in jets.

The UPBT contribution of the Qantas loyalty scheme was $328 million.

The shafts of sunshine in today’s guidance from Joyce include a return by Qantas domestic to the high yields it enjoyed in FY ’08, meaning that when it does sell a fare, it makes really good money.

Joyce declared that the demand for premium fares was also returning to good health on international routes, but qualified that by saying that compared to the pre GFC days of 2008, average yields on fares were still down 11%, but climbing steadily.

Good, bad, good. There was a lot of bad jam sandwiched between good bread this morning.

The group was also making its best money yet out of freight, and uniquely positioned through Jetstar to grow capacity rapidly to cater for increased demand, choosing whether to do this in Australia, or New Zealand, or in its Singapore-based Jetstar Asia subsidiary, which made $SIN 6.9 million in the last year, which makes it look very competitive with the Singapore Airlines controlled Tiger Airways group.

For investors, however, it is an intriguing outlook, full of shafts of sunlight between dark clouds of uncertainty, and the pain of missing out on a second half as well as first half dividend.

Qantas shares lost up to three cents in early trades, to $2.48, which was less painful than the losses being seen in the broader market this morning.

I am reminded of the ever popular accounting acronym, PBBS, or for the rest of us, Profit Before Bad Stuff.