Federal Labor faces a profound identity crisis and the party’s leadership — and most of all Julia Gillard — must put together a coherent vision for her government and a strategy for achieving it.

Yesterday’s Essential Report was awful for Labor, and not just for the unsubtle symbolism of Labor falling behind on the 2PP vote for the first time.

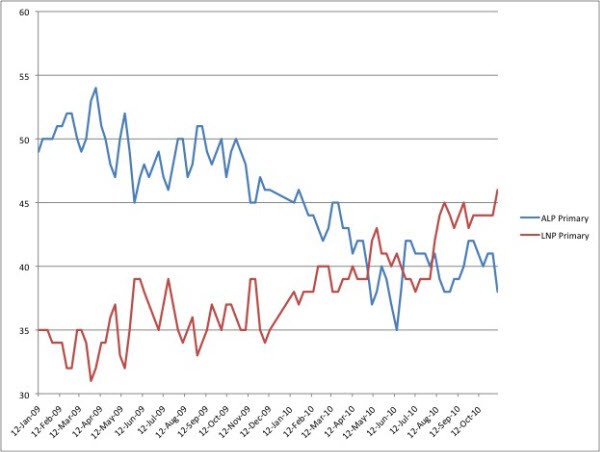

Labor and Coalition Primary Vote 2009-now

Labor’s primary vote has been in decline since the end of 2009. Kevin Rudd hit bottom in June this year at 35%, began pulling back, before being knocked off. Julia Gillard provided a temporary boost, but even in her honeymoon as new Prime Minister she never threatened 45%. Now it’s back below 40%.

More damaging were the data on perceptions of which party was best at handling issues. Labor really only had a substantial lead on one issue: improving wages for low-income earners, where it led the Coalition by 14 points. It led on the age pension by 4 points. It was about even or trailed on everything else — unemployment, housing affordability, prices, government debt (where it trailed 27 points), regulation of banks and large corporations, jobs going overseas. It even trailed on the Coalition on superannuation, 18%-27%, despite the Coalition having a super policy that not even the retail super industry supported.

It’s one thing for Labor to trail on government debt, or taxation. But for Labor to trail the Coalition on core party issues such as superannuation and housing affordability reflects serious damage to the Labor brand. If voters don’t regard it as capable of handling even its own key issues as well as the Coalition, they’re not going to vote for its candidates.

Labor has a problem that the Liberals simply don’t have: what does it uniquely stand for? As a party of the Left, Labor has faced this problem since the Cold War came to an end and the Washington Consensus on economic management was established, but Hawke and Keating’s deft embrace of the Consensus ahead of the Coalition staved off the issue for a political generation. Now, however, it’s more acute than ever.

The Liberals are associated by voters with some basic principles. They balance budgets. They preside over strong economies. They keep taxes low. They beat up on asylum seekers. The reality may be at odds with the image, but that doesn’t change the association in voters’ minds. Apart from IR, Labor seems adrift when it comes to basic principles. It’s a problem akin to the one the Nationals, another party traditionally supportive of state intervention and a regulated economy.

Throughout their time in office, when their proximity to the Liberals raised questions about their identity and what they really stood for, sufficient to create room for a populist revolt in the regions. Indeed, given just on half of voters believe the Labor and Liberal parties are becoming more alike, it’s a problem that will only get worse for Labor. If Labor is just about economic reform and managerial competence, then voters will gravitate toward the Coalition, regardless of how competent and reformist the latter are, particularly given the relentless partisanship of some News Ltd outlets in generating myths about Labor incompetence.

The Liberals have what might be called brand strength not just because they’re on the right side of history on economic policy, but also because of John Howard. Howard might have backflipped on key issues such as Medicare and immigration over the years but his sheer longevity meant that voters instinctively knew where he was coming from. Labor drew similar strength from Hawke and Keating.

For all that the Labor Party needs to define itself better, its leader is critical to the process of assuring voters about where a Labor government will take the country. Elected prime ministers have a direct relationship with voters, apart from that mediated by their parties. And part of that relationship is giving voters a sense of what goals the prime minister has, and how he or she wants to achieve them.

Hawke, Keating and Howard had that. Rudd began with that, but his mixed messages on asylum seekers and his retreat on the CPRS confused voters. Julia Gillard, who began her prime ministership with a huge backdown on the RSPT and promptly confused things further with a citizens’ assembly on climate change and a return to offshore processing of asylum seekers, has never had it.

We know the prime minister is passionate about education (then again so, too, was Kim Beazley, who wanted to be known as “the education prime minister”). We know she wants to “reform”, although for what end isn’t clear. But where’s the framework that incorporates the economy, social policy and foreign policy? What are the pillars of Labor policy that guide it and will never be retreated from? Even Rudd’s effort at a long-term agenda early this year, around productivity and health reform to address an ageing population, has disappeared off the radar.

Given the electoral cycle, Labor has got time to get its act together, and it is assisted by the fact that it is up against an inept Opposition (think of what sort of majority prime minister Costello would have racked up if he’d bothered to stick around). But if left unaddressed, this identity crisis will keep driving Labor’s primary vote lower and lower until it hits bedrock.

What should Julia stand for?

GAY MARRIAGE.

The clock is ticking. The next election will be some time before the end of 2013.

National Conference in 2012 = BAD MOVE.

Bring the conference forward to 2011!

Bernard, you raise an especially pertinent point ie: one wonders at the self-loathing Costello must currently put himself through. So easily the prime ministership could have been his for the taking.

At least Turnbull had the sense to do an about-turn and be patient for the ultimate prize.

What is the ALP motto now? ‘Power for Power’s sake’? ‘Reform through Inaction’? ‘Government of the committees, by the committees, for the committees’?

There are always egomanic businessman to fill up the ranks of the Liberal Party. The ALP on the other hand is limited to a much smaller pool of political operatives who have never been exposed to the ‘real world’ in their life. To them, ‘conviction’ means somebody being locked up, their policy is whatever the opinion poll says.

For example, Mark Arbib and Paul Howes have announce a support for gay marriage. For the overwhelming majority of Australians the issue doesn’t resonate. Unless Mark Arbib and Paul Howes MARRIES each another, most voters will recognize it as a cynical ploy to win votes from the Greens, and at the same time undermine Julia Gillard who is oppose to gay marriage.

Politics is about narratives. The ALP made a mess of the Mining tax because it looked like they’re slugging the miners to fill up a black hole. Cutting company tax by 2% and increasing super to 12% does not stir the imagination. Imagine what would happen if they had said that the revenue from the Mining Tax will be ‘ring fenced’ and used to fix the Murray Darling? It would have changed the tone of the debate even when the impact on the budget is the same.

If I could put a slightly different slant on Ronin’s comment, for the mining tax (RSPT) to succeed, Labor needed a consistent and simple public message about what it was, how it would work and why it was necessary; an excellent PR campaign to sell the message and combat the big miners’ advertising; and consistent, persuasive leadership from Rudd and Swan. All of this was missing. Little wonder Gillard decided to compromise.

ronin8317 – actually, gay marriage IS an issue that resonates with voters, on both sides of the equation.

Those who are vehemently against it – for whom it is a game-changer – don’t vote Labor anyway and probably never did. Labor will lose no votes from here.

Then there are those who are vehemently in favour of it – for whom it IS a game-changer – and these people have either already shifted from Labor to the Greens or are on the verge of it. These votes will continue to bleed as more and more left-wing Labor voters (and members, if we are being frank), who have been giving the party (and Julia in particular) the benefit of the doubt, begin to realise that things are not about to change in a hurry.

In the middle there are the vast majority of Australians who either agree or disagree, but for whom (either way) the issue is not a game-changer. Those who disagree are squeamish about homosexuality, but they have more important things on their minds. Those who agree just think about it being essentially a human rights/equality issue but, again, have other things on their minds.

The bottom line is this is an issue that the Labor Party can’t lose on – which is why it makes no sense that they aren’t going down this road.

Part of the problem the Labor Party has – not just Julia Gillard – is what the essence of this article is about; that people don’t know any more what the party stands for. There was a time that the ALP was out there stridently supporting the downtrodden, disenfranchised and discriminated, but these days they are just as likely to be standing toe to toe with the Coalition in the race to the bottom.

Under these circumstances, why would you bother to vote Labor? You would either vote for self-interest (Coalition) or for the good of all (Green). And there’s the rub. Where exactly is the ALP in all this?