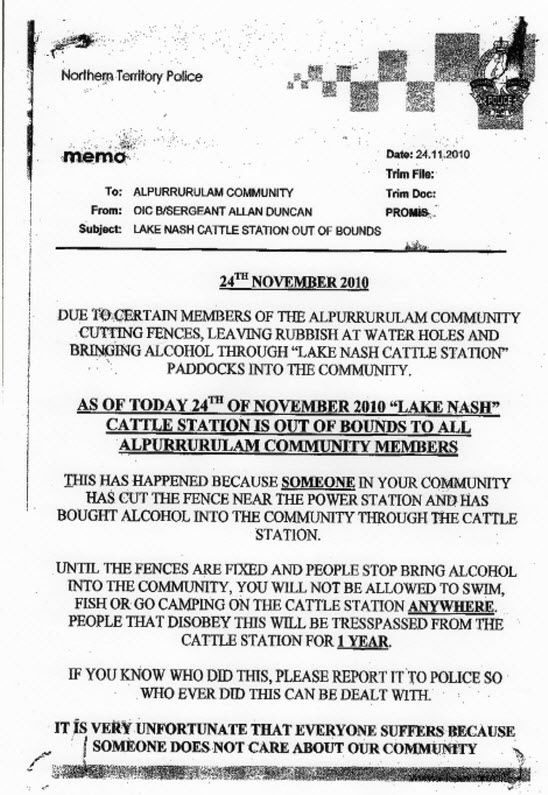

Last Wednesday afternoon Brevet Sergeant Allan Duncan, officer-in-charge of the Alpurrurulam police station, posted this NT Police memo outside the store of the small Northern Territory township of Alpurrurulam:

In part that memo told the 600 or so mainly Aboriginal residents of Alpurrurulum that:

“AS OF TODAY 24th OF NOVEMBER 2010 “LAKE NASH” CATTLE STATION IS OUT OF BOUNDS TO ALL ALPURRURULUM COMMUNITY MEMBERS

…

UNTIL THE FENCES ARE FIXED AND PEOPLE STOP BRING (sic) ALCOHOL INTO THE COMMUNITY, YOU WILL NOT BE ALLOWED TO SWIM, FISH OR GO CAMPING ON THE CATTLE STATION ANYWHERE. PEOPLE THAT DISOBEY THIS WILL BE TRESSPASSED (sic) FROM THE CATTLE STATION FOR 1 YEAR.

…

IT IS VERY UNFORTUNATE THAT EVERYONE SUFFERS BECAUSE SOMEONE DOES NOT CARE ABOUT OUR COMMUNITY.”

Alpurrurulum, seven hours or more drive north-east of Alice Springs, is one of the most remote townships in the NT. The people of Alpurrurulam were moved off their traditional lands by the pastoral invasion of the late 19th century and have a proud record as the best cattle workers in the region, and an equally proud record of fighting to hang onto what little land they’ve been able to wring from the grasp of the pastoralists and governments.

“Lake Nash” is the European name of the permanent waterhole on the Georgina River and the massive cattle station that surrounds the Alpurrurulam community. At 854,700 hectares it is one of the largest and, in good seasons, one of the most productive cattle stations in the NT. In the long years of drought, the region is little more than a wasteland and dustbowl — but in good years cattle will be belly-deep in the Mitchell Grass plains that dominate the vast Barkly Tablelands of the central-east of the NT.

Until the late ’80s, the community lived in a scrappy collection of humpies and tin sheds by the waterhole and close-handy to the station homestead. With the growth of the community, that site, which flooded every wet-season, was no longer suitable. After long and difficult negotiations between the pastoral company, the community and the NT and federal governments, the community moved to their current location a few kilometres to the west of the Georgina River.

One of the biggest sticking points in the negotiations concerned access to Lake Nash itself. As one of the traditional owners of the land recounted in a book (*) that told the story of their connection to and fight for their small scrap of land:

“The waterhole over there belongs to Aboriginal people. It is Aboriginal ground. The white people named that place Lake Nash, but its real name, its Aboriginal name is Ilperrelhelame. A long time ago, the [old men] took the sacred things from here and hid them in case white people came and stole them … Aboriginal people own this waterhole. We look after this place as those before us have always done.”

Another old man told of the representations from the pastoral company that were subsequently reflected in an easement in favour of the community granting access to the waterhole and the sacred sites nearby:

“Bassingthwaite came and told us, ‘You fellas can still use this creek [waterhole] for fishing, the same as before. And when you blokes go out around bores, just look after the gates. That’s all. Don’t leave them open. It’s finished now, no more argument’.”

It is in this historical context that Sergeant Duncan’s memo, purporting to unilaterally punish the whole community for the actions of a few, provoked a wholly predictable response of outrage and anger.

The mob at Alpurrurulum know all about anger — but they also know about the value of direct action. In the hard years following the Second World War they regularly went out on strike against harsh treatment from the Lake Nash station management.

Ironically they were initially encouraged to do so by the local police sergeant.

As Flash George Mahoney said in the late 1980s(*):

“We were working for no money and this old sergeant … said to us, ‘Why don’t you blokes tell him to pay you? The station is getting all the money now, and you blokes are still working for nothing’.”

Late last week community members hit the phone to lawyers at the Central Land Council in Alice Springs, who in turn contacted regional Superintendent Megan Rowe in Tennant Creek, the OIC for the district.

The CLC advised the Alpurrurulam community that the memo was most likely unlawful and without effect for several reasons, including that it may have been in breach of:

- the 1989 registered easement in favour of the local community that gave them rights of access for traditional Aboriginal purposes including “visiting sacred site, performing traditional ceremonies and swimming and fishing”.

- Subsection 38(1)(n) — (Reservations in favour of the Aboriginal inhabitants of the Territory) and section 79 of the Pastoral Land Act of the NT.

- Section 47 of the of the NT Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act — that grants rights of access to Aboriginal people to sacred sites on pastoral and other lands.

Alpurrurulam local Willie Bookie told Crikey that he sympathised with Sergeant Duncan. But Bookie also noted that there were serious problems with communication between the NT police and the local community:

“It [the memo] was a bit rough but he just wanted people to bring that boy up to the place where they could speak to him and ask him straight out if he done that and for him to go back and fix up that fence…

“He [Duncan] is kinda a new chum — he doesn’t know anything — he doesn’t know what the old people explained to him here — you know, what’s in that area …

“We’ll have a meeting with the police when that brevet sergeant comes back. Probably the station owner as well [and we’ll] tell him how things run here and all that.”

Crikey asked the NT police several questions about Sergeant Duncan’s memo and any further action they would take in regard to the actions of sergeant Duncan.

Yesterday Tennant Creek Regional Superintendent Megan Rowe forwarded a statement to Crikey advising that:

“The notice was issued in error and without authorisation by an individual officer who was mistaken and incorrect in his response to an issue of damage and littering on the Lake Nash Cattle Station. The notice was not authorised by the Officer’s supervisor. The notice was brought to the attention of B/Sgt Duncan’s Divisional Superintendent on the afternoon of Thursday 25 November. On instruction from Superintendent Megan Rowe, all public notices were taken down by the members of the Alpurrurulam Police Station who also issued immediate apologies for the incorrect information outlined in the notices. The notice is not in force and never held any legal authority. B/Sergeant Allan Duncan at Alpurrurulam has been a member of the NT Police Force since 12 October 2009 however was previously a member of the Victorian Police Force for almost 10 years.”

(*)We Are Staying. The Alyawarra Struggle for Land at Lake Nash. Pamela Lyon & Michael Parsons, IAD Press, 1989.

There’s someone in every community / block of apartments, whatever that puts up notices like that. The best thing you can do is tear them down quickly before they upset too many people.

Yeah, and a memo like that maybe wouldn’t look out of place in a primary school.

But from law enforcement? To an entire community? Its a disgrace.

So what’s the story then? That naive isolated cops sometimes make mistakes? or that Gosford is a superior intellect and is compelled by honour to tell the breathless world about the great threatening evil contained within this single minor authoritarian act, for which the poor Brevet sod had already been humiliated??