Ingrid Piller from Language on the Move writes:

My daughter attends a public elementary school in NSW where the children are taught French for one hour each week. In 2009, she was away from her school and did not receive any French instruction during that year. When she returned, it turned out that she had not missed anything and was at exactly the same level as the children who had received an additional year of French instruction.

While I’d like to pride myself on the idea that my daughter is exceptionally gifted in French, the reality is that the other children had made no progress whatsoever in that one year. As a matter of fact, after more than three years of French instruction, the knowledge of this particular group of children is negligible: the only “sentence” they can confidently utter is “Bonjour, Madame!”. They can count from one to 10 with difficulty and their pronunciation of these numbers is shocking. In more than three years, they haven’t learnt a single point of French grammar and as they are not required to memorise the words they are taught, they have difficulty even with such basic vocabulary as colour or animal terms.

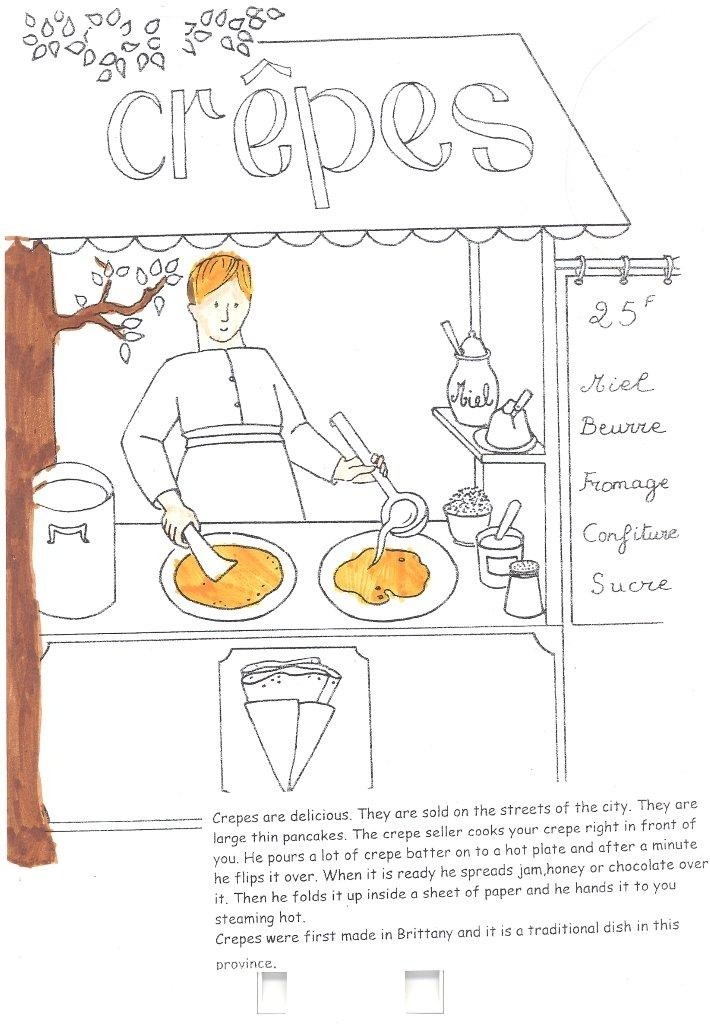

The only perceptible knowledge children are gaining in this kind “language teaching” is stereotypical and pseudo-cultural information about France, such as the fact that the national dress includes the beret or that French people love pancakes.

A French lesson in another school consisted of a colouring in competition with a joint reading of the English information at the bottom of the worksheet. The student from whom I got the worksheet quickly lost interest as is evident from the fact that only two colours were used in a perfunctory way. At no time were the five vocabulary items in the right-hand column even highlighted or brought to the learners’ attention.

Over the seven years of elementary school, 40 hours of French instruction per year add up to 280 hours. Given the meagre to non-existent outcomes I have just described, these are 280 hours wasted. The reasons for this waste are complex and include the following:

- Insufficient time on task: one hour of language learning per week just doesn’t get you anywhere. Most European countries devote much more time to language learning and still manage to perform at the same level as or at even higher levels than Australia in literacy and numeracy in international assessments.

- Lack of status: French (or any other language that a school might adopt in NSW) is not considered a key learning area, which means no one is taking it seriously. On the report cards it appears in the same section and format as participating in the school band, the chess club or similar voluntary activities. The teacher is a casual who only comes along for French lessons.

- Poorly qualified language teachers: Many of the language teachers I know here eke out a living as casuals serving a number of schools where they teach often more than one language, none of which they may be particularly proficient in. Their qualifications and language proficiency often are not great to begin with and then their precarious employment becomes a disincentive, if not an obstacle to pursue any kind of professional development.

- Confusion between language and culture: language learning is first and foremost learning the four skills of listening, speaking, reading and writing. Language learning in school should be about learning pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary and texts. Questions of culture and identity come much later. For French teaching to be mostly about berets and crêpes would be like teaching maths by looking at photos of Einstein and learning that mathematicians favour crazy hairdos.

None of this is new and it is only a slice of the disaster that is Australian languages education. Three of Australia’s leading linguists, Michael Clyne†, Anne Pauwels and Roland Sussex called languages education in Australia “a national tragedy and an international embarrassment” in 2007.

Now the draft for a new national languages curriculum has been published for consultation by the government (the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). While it is encouraging to see that the draft curriculum makes languages education compulsory for all through all levels of schooling, I’m disappointed to see that none of the concerns I have highlighted above as key problems are addressed in more than a perfunctory manner. The problems of insufficient time on task, lack of status, poorly qualified teachers and the over-emphasis on culture and identity at the expense of actual language learning will not go away with the introduction of this national curriculum. There is no recognition of the existence of these problems in the draft document, let alone a strategy for addressing them.

None of this is new, as I said, and so it beggars believe that most of the existing research into Australian languages education is completely ignored. The National Curriculum team would be well served by having a read of Michael Clyne’s indispensable work Australia’s Language Potential. Our children deserve better than colouring books

Crosspost from Language on the Move

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.