Much of the criticism of middle class welfare has been directed at the Howard government, which in 2000 overhauled the family payments system to establish Family Tax Benefits A and B as part of the tax system overhaul.

Family Tax Benefits are not middle class welfare per se, of course. The bulk of FTB payments go to lower-income households. But it becomes middle class welfare — a term John Howard loathed — when you don’t restrict access to FTB to people on low incomes.

What’s a low income? Well, full-time adult average earnings at the end of 2010 were just under $69,000 pa. So let’s agree households on over $100,000 a year don’t qualify as low income, however much they may tell journalists they “don’t feel rich” and “struggle to make ends meet”.

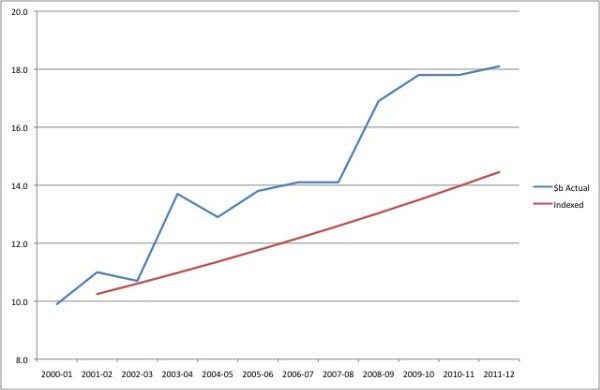

In the first year of Howard’s new FTB payments system, payments were forecast to cost just under $10 billion.

Family Tax Benefit payments (actual except for 2011-12) and 2000-01 payments indexed, $b

In this week’s budget, 11 years on, they’re forecast to cost $18 billion in 2011-12. FTB payments have risen much faster than inflation (I used an index of 3.5%). And some of the biggest growth was in 2008-09, the first Rudd government budget when, despite curbs on eligibility for both the baby bonus (a tiddler of a program at around $1 billion a year) and FTB, spending leapt $2.8 billion. That’s because FTB is a favoured vehicle for governments to bribe middle-income voters in the run-up to elections.

If FTB payments had merely grown at normal indexation rates, we’d have had over $26 billion extra in the budget over the last decade.

In short, FTBs are now Labor’s as much as they are Howard’s, which makes the “war on the middle class” rhetoric from News Limited and its journalists even more risible. Howard might have carefully nurtured a sense of entitlement amongst Australians, but Labor has, rather than tackling it, adopted it. One of the strongest defenders of middle class welfare — or family payments, as he calls it — this week has been Wayne Swan himself, despite the witless illustrations to be found in the pages of The Daily Telegraph.

In this, Swan stands outside Labor tradition. The strange ideological flip that has the Coalition supporting unmeans-tested handouts while Labor — purportedly — cuts them back first emerged in the 1980s, when the Hawke government introduced means-testing for pensions, and the Howard-led opposition screamed in outrage, even while it ran televisions ads in the 1987 election campaign accusing Labor of handing out welfare to the undeserving. In fact, in the Hawke-Keating years, Labor was the party of rigour when it came to welfare.

But attitudes toward welfare have always been based not on the policy rationale for it, or on who needed it, but on who was receiving it. People who actually needed welfare have always come under ferocious scrutiny, while those who didn’t have got away decidedly easier.

Forgive the nostalgia, but Australia has, clearly, changed, and not for the better. In the Australia I grew up in in the 1970s, the middle class was proud of its self-reliance, proud that it received no handouts, from government or anyone else. Welfare was seen in some quarters as left-wing income redistribution, bordering on socialism. This partly fueled the remarkable wrath directed at the unemployed under the Fraser government, with incessant media coverage of lazy surfers spending all day sitting on a beach, funded by unemployment benefits.

The language was different, too. People talked about “welfare” and “the dole”. Now, of course, we talk carefully about “transfer payments” and “family payments”. I mean, goodness gracious, no one earning $140,000 would like to be told they’re on “welfare”.

A personal note: I suspect I absorbed those seemingly quaint sentiments, despite being raised in a low-income household. I retain to this day an aversion to unearned income. Don’t get me wrong, I love money — some of my best friends are money — but I don’t want it if I haven’t earned it. That’s probably why I don’t gamble, in addition to the fact that I regard games of chance as a tax on the innumerate. Or maybe it’s because, apart from a brief period early in my parenting years, I and my partner never qualified for any handouts. Perhaps my ongoing fury at middle class welfare is just a lifelong exercise in downward envy.

But whatever the case, clearly, my puritanical streak is at odds with the sense of entitlement and of handout entrepreneurialism abroad in the community, in which any and all handouts should be harvested.

Because, it’s not merely that governments hand over nearly $20 billion. If you’re eligible — if your household income is below $150,000 — you don’t receive the payments unless you apply to the Family Assistance Office. High income earners — families earning over $100,000 a year, let’s say — have to choose to get FTB. That is, high-income earners make a conscious decision to take handouts from government, despite their relative wealth compared to most of the population.

Of course, it’s entirely legal for them to do so, and the prevailing sentiment is quite the reverse of pride in self-reliance — a failure to hunt down every single handout for which you’re eligible is almost a personal failing, doing the wrong thing by your family, almost unAustralian.

As I noted yesterday, however, it’s our children and their kids who will pay the price for this indulgence. They will pay via higher taxes to support us in our dotage, in a fiscal framework in which structural deficit and inbuilt generosity remain prominent features at the point where the impacts of an ageing population are going to start to become apparent. That’s the irony of the argument that middle class welfare rewards people for raising children. Middle class welfare isn’t merely an issue of equity, or of quaint olden days values of self-reliance, but more particularly a growing fiscal problem that we’ll pass on to the very kids we’re using as fig leaves to justify indulging ourselves.

And in the Australia I grew up in, people who took welfare when they didn’t need it were called “bludgers”. It’s not clear why, despite the entitlement mentality on display in the media this week, that same term shouldn’t be applied to households earning substantially over $100,000 a year who choose to receive Family Tax Benefit payments. Aspirational, maybe. Working families, yes. But bludgers, as well.

But of course, that would never do.

Very well put Bernard! I laughted out loud. Especially at: [People talked about “welfare” and “the dole”. Now, of course, we talk carefully about “transfer payments” and “family payments”. I mean, goodness gracious, no one earning $140,000 would like to be told they’re on “welfare”.]

Hey I use to know quite a few “lazy surfers spending all day sitting on a beach, funded by unemployment benefits”! That lifestyle lasted less than a year for them: they got bored and looked for ways of earning more money because they eventually realised that most of the things they wanted were not going to come to them on the dole!

Back in the good old days, your mother would have received the Child Allowance payment, the non-means tested precursor to Family Allowance, Family Payments and Family Tax Benefits.

The history of its renaming speaks volumes. It is now effectively tax relief for people with children.

It used to be an allowance for (mostly) non-working mothers who otherwise had to rely on their husbands for housekeeping money.

The middle class is bludging and whining alright.

I haven’t applied for my Seniors card because I don’t need discounts. My pride gets in the way. In fact, I prefer to pay full price and leave a tip for good service. Why don’t businesses just give the discounts to the unemployed and the age pensioners?

Likewise, I haven’t applied for a non-means tested Carer Allowance because I don’t need the money and I don’t want the hassle of the application process and the assessments.

Where did our self-reliance disappear to?

People living in McMansions who have been pretending to be rich are now publicly proclaiming how poor they are. It’s their own fault for trying to keep up appearances.

Judging by the outrage at the ALP because the are cutting off any family over $150k (about 15% of households) they would of been absolutely crucified if they had tried to cut it back further. The Herald Sun had more than 80% of people claiming they would be worse off under this budget and Abbott is running his “tougher on families than on border protection line” and off course it getting a good run on talk back and News Ltd papers, so just imagine if what they were sayng was actually true!

Haha! “some of my best friends are money” — it’s GOLD!