Treasury boss Martin Parkinson has called for Australia to lift productivity and wants a return to structural reforms to boost our productivity. Parkinson is right about the need to lift Australian productivity but he is wrong in isolating future increases to major reforms. The current problem starts with Parkinson himself (and his predecessors). As treasury secretary, Parkinson can personally take actions that will transform Australian productivity, and until he does accept personal responsibility and takes those actions, Australian productivity will continue to decline. I must also add that major structural reforms will also lift productivity, but they take a long time whereas Parkinson is in a position to move quickly.

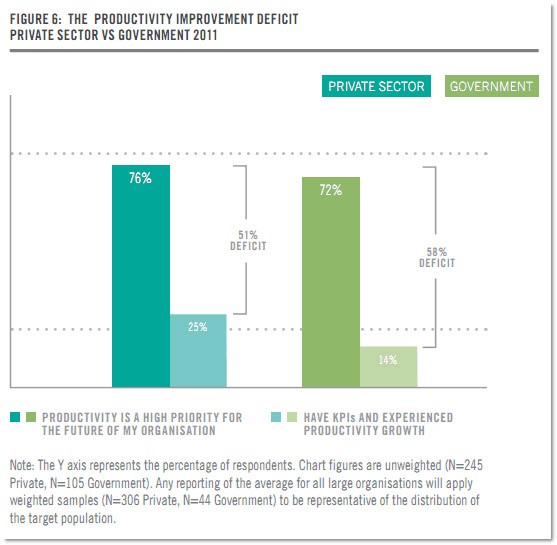

According to the Australian productivity guidebook — the Telstra Productivity Indicator — some 72% of Australian and state public servants believe that productivity is a high priority for their organisation. In other words, they accept the Parkinson urgency in principle. But a miserable 14% of public servants actually measured their productivity and had key performance indicators related to those measurements. In other words, in the public service productivity is not taken seriously.

Parkinson’s first job is to start with Canberra and use his power first to determine tough productivity measures for government employees and contractors and second to tie public service promotion and the allocation of money to improving productivity. It’s true that Parkinson does not have the power to implement that change, but once he accepts responsibility he can drive it a long way.

Cynics say the current definition of productivity in Canberra is related to lifting staff numbers and expenses, so Parkinson must move outside the public service barons and find simple ways to measure government productivity. It will not be easy.

As it happens, today’s Liddington-Cox graph shows that the private sector is not that much better, with 76% of corporate executives giving a high priority ranking to productivity but only 25% saying they measure it and so are in a position to do something about it.

Telstra defines the gap between stated priorities and action as the productivity “deficit”. In the public service that “deficit” is 58%. I pointed out the productivity shortfall in my commentary (Australia’s missing productivity link5). Parkinson will also find useful the excellent conversation that followed my comment.

There are some companies that are very good at productivity measurement, including Orica and Rio Tinto. Parkinson’s people should start with those organisations and then adapt the lessons to the public service. Obviously there will be overseas examples to learn from.

And once Parkinson has taken the initiative he can then chide the private sector to lift productivity. Parkinson was right in alerting Australians that falling productivity threatens their living standards (and corporate profits). And he is also right that reforms can deliver in the long term. But the really big gains will come when Canberra and state public servants, plus corporate CEOs, start measuring their efficiency and are therefore in a position to do something about it.

*This article was first published on Business Spectator

Dr Harvey M Tarvydas

Good one RG. A classical reminder with proof that now that they have all got off with talking about it the time has come to start the ‘action’ event and get the goodies.

“Productivity” still means doing more work for less wages, right?

I have yet to see productivity improved by performance indicators, key or otherwise, and still less by the measures of individuals’ productivity advocated by Gottliebsen.

For example, universities are awash with personal and organisational performance indicators which has diverted an immense amount of time to their collection and reporting, much done by the administrators about whom acas complain perpetually. Yet student:staff ratios have increased from 12.9:1 in 1990 to 20.6:1 in 2004 and have kept at that level since, an increase in productivity of 59%. Nothing to do with performance indicators.

‘Parky’, ie Michael Parkinson is good, but Treasury Secretary material he ain’t. Martin Parkinson on the other hand, no good at interviewing but quite good as Treasury Secretary think.

One of the real measures of productivity would be where decision making lies. In Canberra a person used to be an ASO5 if they were responsible for the photocopying. Now that is at least 2 levels higher. ASO 6’s used to run offices of 40 people – now they are lucky to manage 2 or 3 and if they want to make a decision have to go up the line and wait. So I would suggest that lowering the levels with delegations and making decisions within a week would be two good places to start.