When Brigham Young stopped in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 and said ‘This is the place’ to his Mormon followers, thank goodness he was too worn out to head south. For the quite beautiful but heavily populated valley in northern Utah, home to the largest community of Mormons in the US, pales in comparison to the awe-inspiring landscapes of southern Utah, which have remained sparsely inhabited and relatively unknown to ensuing generations of American travellers.

When Brigham Young stopped in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 and said ‘This is the place’ to his Mormon followers, thank goodness he was too worn out to head south. For the quite beautiful but heavily populated valley in northern Utah, home to the largest community of Mormons in the US, pales in comparison to the awe-inspiring landscapes of southern Utah, which have remained sparsely inhabited and relatively unknown to ensuing generations of American travellers.

In fact, I prevaricated over whether to even write about the southeastern corner of Utah we explored, as it feels like the sort of place that should remain unscathed by the relentless traffic of a highly mobile population — its emptiness is an essential aspect of its overwhelming appeal.

But then I reasoned it’s not like I have an audience like Lonely Planet, and they’ve already written it up, and you’re all so lovely I know you won’t spoil it.

On our way into Utah from Colorado, we made the obligatory stop at Four Corners, where the kids and I joined the millions of families before us who have stood concurrently in Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado while maintaining eye contact. Atticus was not torn asunder yet experienced four limbs in four states, and then filled his belly with Navajo fry bread as we trundled back along the highway to enter Utah proper. The towering monuments of southern Utah commenced almost immediately and led us to pause and dine on our first Navajo taco under the Twin Rocks in Bluff.

Having successfully navigated the steep backroads of the Appalachians and the high road to Taos, it seemed only right to take the most direct and scenic highways to Natural Bridges National Monument, and so we drifted down the lonely road towards Highway 261, stopping regularly to gaze in wonder at the dry bottom-of-the-sea views in which the RockVan played the part of the Yellow Submarine on wheels.

We barrel laughed our way past signs warning against vehicles over 10,000 pounds (we’re something over 11,000…) and informing us that the road ahead was ungraded, all the while straining our eyes to work out just how the hell this road was going to climb the 2000-foot mesa wall directly in front of us.

It is a testament to the marvels of engineering that the 3-mile switchback road does in fact lead one straight to the top of Cedar Mesa without help from any convenient valley, and a credit to GMC that our 34-year-old RockVan was able to climb it. The western adventures that had commenced in New Mexico kicked up a notch here in these first hours in Utah.

Natural Bridges epitomises Utah’s underwater feel by holding its marvels below the mesa level in a series of serpentine canyons best explored from the bottom. And so in a gentle rain the morning after a night in our most beautiful campsite yet, the Jonai descended into flash flood territory for a 5-mile hike under two of the Monument’s famous bridges. Sipapu Bridge is the second largest natural bridge in the world, and well worth the series of ladders and steep rock faces one must scale to clamber down below it.

All senses were heightened as we ambled past a series of small waterfalls appearing from the now-steady rain swelling the newly-flowing creek along the canyon floor and left our footprints alongside fresh coyote tracks stalking those of the common mule deer.

Just when we started to wonder whether we might have taken the wrong canyon at the fork a mile or two before, we discerned Kachina bridge out of its camouflaged position against the myriad reds and browns of the canyon walls. A rattlesnake spotting as we returned to the RockVan via the mesa top blanketed with intriguing cryptobiotic soil crusts was the perfect climax to our soggybottom bushwalk, and dry clothes the ideal epilogue.

From remote Natural Bridges, it’s an easy 120 miles to Moab, a mountain-biking mecca and great hub for exploring Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. With a couple of breweries and a plethora of outdoor adventure outfits, there’s fun for all ages and hours, not to mention the last wild stretch of the Colorado River before it’s dammed into Lake Powell.

Arches National Park is pure vertical visual impact — monoliths galore in all sizes and shapes to constantly tempt the eye. From the awkward balancing rock to petrified dunes and the Fiery Furnace, surely even geologists must occasionally scratch their heads at just how such a wonderland was created.

Some of the massive rock swirls reminded me oddly of illustrations of air or water turbulence, as though the gods came hammering through here in mighty ships, leaving a stony wake to confound generations to come. There are over 2,000 sandstone arches in the park, yet the eye never tires of straining to catch sight of just one more.

Whereas Arches was jam-packed with tourists, Canyonlands National Park was far more sedate, allowing for quiet reflection on our insignificance in such vastness. And yet Canyonlands’ grandeur surpasses that of any vista I have witnessed. Having been to the Grand Canyon a number of times, I am stumped to understand how it remains more famous than its nearby cousin, where the canyons never end, and include river gorges under mesas layered within canyons.

There are no fences on the many walks along the rim, offering the casual bushwalker a taste of the importance of paying attention and an intense experience of personal responsibility — no sign of any nanny state here. And the rim is exhilaratingly high — it’s some 1200 feet straight down to the White Rim from where we camped and walked on the Island in the Sky, and another 1000 feet down to the Green River Gorge. The neat curl of the Green River in the distance evoked an archetypal longing in my core for the harsh simplicity of the 19th-century cowboy’s life out here. I’m sure a couple days actually out there in the hot sun would take care of it though.

Having scored one of the very few precious campsites actually within Canyonlands National Park, we awoke to the cacophony of what we took to be a dozen Mormon children in the site next to us, tended to by two sister-wives and overseen by one solid bearded father. As we sat down to our poached eggs, the chaotic chatter died down then unified in song — a sound that soothed, gathered and carried far across the mesa to fade away far above the canyon floor.

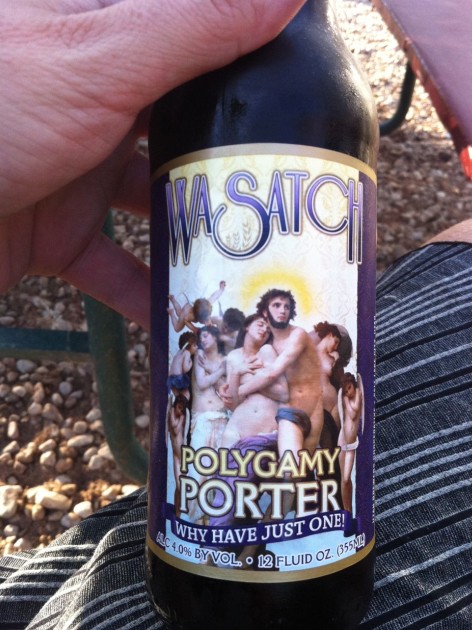

The public practice of polygamy was officially denounced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1890, though there are still thousands of polygamists in what I suppose are basically splinter sects from the Mormons. Polygamists are excommunicated from the Church, so cannot in fact be Mormon, and some folks in Utah clearly have quite a sense of humour about the practice, if Polygamy Porter, the local craft beer, is anything to go by.

Having been lifted by song, we made it back to Moab in time for a half day of whitewater rafting on the powerful Colorado. I watched proudly as my children were the first to leap into the water after the guide gave us permission, then followed closely with some anxiety about the incredible strength of this water and its capacity to obscure any capture of unwitting swimmers in its dense ochre depths. And while the rapids were underwhelming that day from the safety of the raft, their mysterious eddies and currents pulled at our limbs in rather exciting and alarming ways as we floated one set in just our life vests.

Our final Utah experience happened far across the state at the northwestern border, where we stopped at the stark Bonneville Salt Flats. The heat makes it clear that this is not snow, but like a Tibetan seeing the sea for the first time, the endless plain of white makes no visual sense at first to those unaccustomed to salt anywhere besides the grinder. After a taste, Oscar declared the salt ‘salty’, and Atticus collected some for me to include in that night’s beef stroganoff.

From monoliths, mesas and mysterious depths, the impossible beauty and surreal landscapes that abound in Utah are imprinted in my cells forevermore. But sssssshh… don’t tell anyone.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.