It may not look it, but there are strong links between the Occupy protests here and overseas, and more formal political debate and public discourse, which naturally has been dominated by the Qantas dispute. And not just in the vague sense that both deal with the economy, or capitalism, or markets.

Let’s be clear about the long-term business agenda in Australia regarding industrial relations. It’s an agenda aimed not at improving productivity — as I and others have incessantly showed, the last round of IR reform led to a drop in labour productivity — but a more self-interested one aimed at reducing labour costs and neutering unions.

Business is quite tolerant of trade unions, as long as they do nothing that inconveniences business or increases labour costs. They can even be a useful form of alternative pressure on governments when industries set about rent-seeking. Neutered unions are quite acceptable. Real ones, that aggressively represent the interests of their members, aren’t. And ones that actually take industrial action, in particular, are regarded as outright enemies of business.

This is the ultimate thrust of IR reform — to pathologise industrial action, however legal, however justified. The point is to frame the right to withhold labour as an illegitimate form of economic vandalism, no matter what the circumstances.

Thus the incessant business complaint that the Fair Work Australia framework is too “pro-union” because it allows unions to take industrial action once a number of legal hurdles have been cleared. And the logic of Qantas’s actions on the weekend was to break free of the normal industrial dispute provisions under which it was operating, in which unions could continue to take wholly legal industrial action which (as Fair Work Australia found on Sunday night) did not pose a significant threat to Qantas.

This is business’s particular self-interested contribution to the liberal economic reform project. The IR component of that project, starting in 1993 with the Keating government’s provisions for enterprise bargaining and accelerating in 1996-97 with Peter Reith’s reforms to deliver individual contracts, was to remove the impediments of a centralised bargaining system from a modern, open economy, allowing enterprises to respond to competition more flexibly.

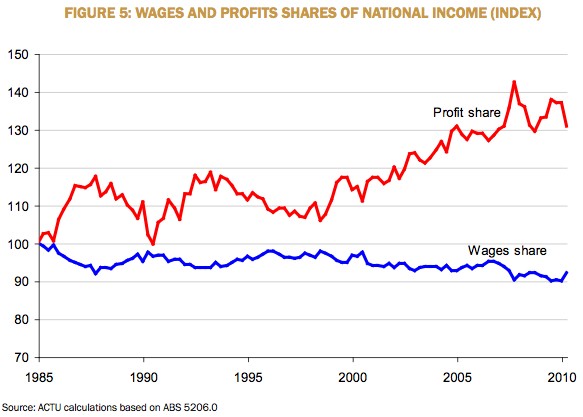

Coupled with globalisation, deregulation and corporate tax cuts, the reform project has delivered a huge increase in the corporate sector’s share of national income — at the expense of labour, as this graph from the Australian Council of Trade Unions shows:

The wage share of national income in Australia has only recently come off historic lows. But on this we’re no different from the United States or the United Kingdom, where wage share has also dropped over the last three decades to historic lows of around 50%.

Australian business clearly doesn’t believe the wage share has fallen low enough. That’s what drives its agenda to go further and undermine collective bargaining, a key part of which is the right to withhold labour, something businesses have been trying to do since the time of the Combination Acts in the early nineteenth century. Australia remains, for its corporate leaders, a “high wage” economy that struggles to compete internationally. For globally-mobile capital, there’s always a lower-wage country somewhere else to move to.

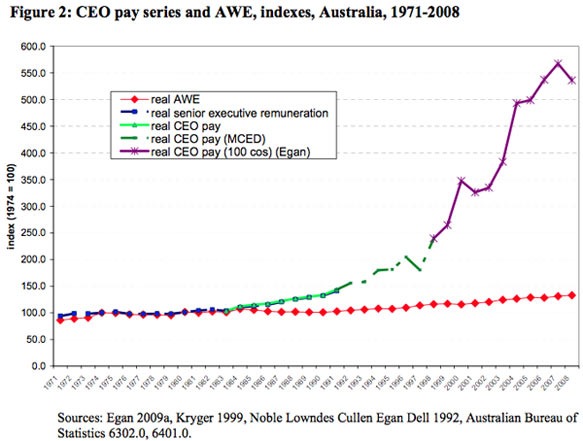

That same global market, however, has been the justification for a massive increase in executive remuneration, which as Prof David Peetz has shown, accelerated in the 1980s but then really took in the late 1990s.

Now, you can look at this from a union perspective and rail about income inequality and overpowerful corporations, or from a corporate perspective and point out that it’s the logic of a global market. And that market is currently delivering strong employment growth and growing income to Australians. But either way, it is driving the growing anti-corporate sentiment in the community, the opposition to further economic reform and the desire to reverse some reforms like privatisation. The Occupy protests are only the most vocal point of this deep and wide community sentiment that corporations get all the benefits of the economic system while the community gets all of the costs.

Where unions have failed is to tap into this sentiment. Capitalism operates most effectively by atomising the individual, by ensuring that an individual’s primary relationships are one-to-one relationships with producers as a consumer, and with employers, as a worker. Traditional systems that establish links cutting across these one-to-one relationships — unions, churches, political parties — have all been in decline in recent decades. Now the internet threatens to establish a different set of relationships and communities at odds with capitalism. But unions still retain some of the power that they once had to disrupt capitalist relationships, which is why business wants to neuter them.

The challenge for unions is to find a way to effectively channel those community concerns. Some of the more politically effective unions, like the Australian Workers Union, would argue that that is exactly what they’ve done through outcomes like the recent steel industry package. They also face an often hostile media environment that reinforces the illegitimacy of industrial action.

Alternatively, the challenge for business is to find a way to address those concerns themselves, to stop the community seeing them as a problem, the beneficiaries of a rigged capitalist game. Continuing to reflexively wage industrial relations wars wouldn’t seem to be the best start in doing that.

www .smh.com.au/travel/travel-incidents/afp-investigates-qantas-plane-sabotage-20111102-1muxm.html

[“The Australian Federal Police are looking into an act of alleged sabotage involving a Qantas plane.

The plane was undergoing maintenance in Brisbane when the alleged incident occurred last week, before Qantas grounded its entire fleet on Saturday during an industrial dispute.

It is understood that after engineers returned from a lunch break, they noticed several wires had been cut on an in-flight entertainment system, The West Australian reported this morning.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/travel/travel-incidents/afp-investigates-qantas-plane-sabotage-20111102-1muxm.html#ixzz1cVfuQM7e

“]

Looks like Qantas are vindicated as grounding all aircraft as a safety measure after announcing the lock-out.

The unions are a safety and security risk.

Wow, a single alleged incident that’s still under investigation is enough to brand unions, generally, “a safety and security risk”?

Probably better to view ‘safety’ as a canard that both sides of the dispute are attempting to harness, as clearly nobody wants planes dropping out of the sky.

What I liked about Bernard’s story was that it pulls back to examine the bigger picture.

Excellent article Bernard.

Geewizz – “Looks like Qantas are vindicated as grounding all aircraft as a safety measure after announcing the lock-out.” Do you know who cut the wires? And the cut wires were to in flight entertainment, hardly a safety risk. Also remember that it was the engineers who reported the damaged wires to Qantas.

The one point I will make is that Australia, unlike the US still has had real wage growth over the past 30 years, in no small part due to union representation.

Is it just me or does Geewiz sound just like Truthie.