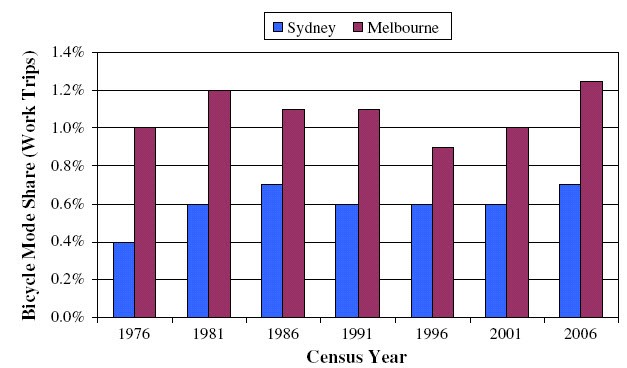

Melburnians cycle for transport twice as much as Sydneysiders and are taking to cycling at three times the rate of their northern neighbours. Moreover, Melburnians are more likely to use bicycles as a means of transport, whereas for Sydneysiders they’re mainly a weekend recreation.

At a time when many suspect the NSW Premier wants to stymie cycling, it’s useful to consider what could possibly explain a difference of this scale.

Fortunately, an analysis of the reasons for the difference between the two cities was published last year in the Journal of Transport Geography, with the title Cycling down under: a comparative analysis of bicycling trends and policies in Sydney and Melbourne. It was undertaken by John Pucher of Rutgers University, Jan Garrard from Deakin University and Stephen Greaves from the University of Sydney.

It’s surprising that Sydney fares so badly relative to Melbourne. Sydney is considerably denser than Melbourne, has a higher proportion of employment in the CBD, lower per capita car ownership, lower per capita kilometres of car travel, and higher walking rates.

These factors should predict higher cycling and higher public transport levels. Public transport does in fact have a significantly higher share of trips in Sydney than it does in Melbourne, but this doesn’t spill over to cycling. The authors identify a number of possible explanations for Sydney’s poorer performance.

First, Sydney is more hilly than Melbourne. The disincentive that brings isn’t just that more effort is required to climb hills. It also means many of the best roads for both cycling and driving are confined to ridge tops, requiring cyclists to share road space with drivers.

Second, Sydney has more natural obstacles, particularly water bodies, which focus traffic on a limited number of choke points. The effect is to increase the distance cyclists must pedal, as well as require them to share heavily trafficked bridges.

Third, access to Sydney’s CBD – which in both cities is a prime generator of bicycle commuter trips – is limited from some directions by barriers such as freeways and the harbour, again forcing cyclists to compete for road space on a limited number of access routes. In Melbourne, cyclists have many more options for accessing the CBD.

Fourth, Melbourne has wider roads that have greater capacity for cyclists to share road space with drivers, either by common use of general lanes or by dedicating some road space for cycling lanes/paths.

Fifth, cycling is not as safe in Sydney. Although data limitations mean it is difficult to make precise comparisons, it does appear that, after allowing for the difference in the level of cycling, Melbourne has substantially fewer serious cycling accidents.

Sixth, Sydney’s average annual rainfall is considerably higher than Melbourne’s, particularly from January to June. Melbourne’s climate is more like countries such as Demark and Netherlands where cycling is high.

Seventh, Melbourne has a longer history and tradition of cycling, both in competitive and utilitarian cycling. While there were around 19,000 work trips per day made by bicycle in Melbourne in 2006 – largely focussed in and around the CBD – there were more than 50,000 in the early 1950s, mostly in the suburbs.

Now all of these factors might at first glance suggest that Sydney could never hope to match Melbourne’s level of cycling (which nevertheless is quite low compared to many European countries). However while they might provide much of the explanation for why cycling is roughly twice as popular in Melbourne, they don’t explain why it’s growing three times faster in Melbourne.

The authors point out that many other cities have enjoyed large increases in cycling despite similar obstacles. For example, San Francisco and Seattle both have hilly and discontinuous topography; Minneapolis, Portland, Ottawa and Vancouver have difficult climates; and Bogota, Barcelona and Paris lack a tradition of cycling being used as a mode of transport (as distinct from recreation).

They attribute the difference primarily to government policy. They say that Melbourne has more cycling infrastructure and what it has is better quality. Further, it is strategically focussed on commuting routes to the CBD. By comparison:

Many of Sydney’s facilities have been ad hoc, uncoordinated, and often located along motorways in the suburbs with limited usefulness for daily commuting.

Melbourne has a denser network of bike routes, lanes and paths, primarily focussed on the area within 10 km of the CBD. They are better connected, better signed and better supported with maps. It has more bike boxes at intersections, more special turning lanes and more advance green traffic signals for cyclists.

Melbourne also has a much stronger institutional environment advocating for cycling. Bicycle Victoria has 40,000 members, 50 staff and can mobilise 500 volunteers for big events, compared to Bicycle New South Wales’ 10,000 members, 10 staff and 100 volunteers.

Ride-to-Work Day has been run in Victoria since 1993, but only began in NSW three years ago. The TravelSmart program and school-related cycling activities are more extensive in Victoria. The authors say:

Many of the experts we interviewed felt that Bicycle Victoria has been a major force behind pro-bicycles policies in Victoria, more effective than Bicycle New South Wales at raising public awareness of cycling and lobbying for improved cycling infrastructure.

Many of the variables that explain the higher rate of cycling for transport in Melbourne are of course inter-related and self-supporting. Once cyclist numbers reach a critical mass, it invites more cyclists and more support from governments, in a “virtuous cycle”. Sydney’s key problem seems to be it lacks a strong cycling culture – understandable to some extent given the more unsympathetic street network.

The authors stress that overseas cities with apparently equally unpromising prospects have developed high levels of cycling by investing in infrastructure and creating a supportive institutional and regulatory environment. They are also keen to emphasise that Melbourne nevertheless has a low level of cycling compared to many European cities.

It’s worth adding that the importance Pucher et al attribute to Melbourne’s focus on the inner city is at odds with a review released last year of the former Government’s cycling policy by the Victorian Auditor-General. He criticised the policy for precisely this reason!

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.