Crikey readers who live in the outer suburbs should sit up and take notice – according to this Fairfax editorial, urban sprawl is making you sick. Moreover, it is “imposing a massive cost on taxpayers, in the form of chronic health and social problems in the new suburbs”.

The main villain is car dependency, which the editorialist claims has led to “an epidemic of ailments caused by obesity, such as diabetes and heart disease, and of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression”. That’s yet another stain on the already blackened name of outer suburban development.

But is it true? Does the greater car orientation of outer suburban communities mean they’re significantly unhealthier than residents in the rest of the metropolitan area? Or do the real causes of health issues like diabetes and depression tend to be glossed over because they’re far deeper and more intractable than resort to an easy and convenient label like ‘sprawl’?

This is a big topic so I’ll have to leave the mental health aspect for another time. Instead, I invite readers to consider this list of “the world’s fattest countries” compiled by the World Health Organisation. Australia is near the top of the pile, but there are twenty countries with a higher proportion of overweight people in their population than Australia. Eighteen of these are countries that aren’t usually described as exemplars of sprawl e.g. Nauru, Kuwait, Barbados, Argentina, Egypt, Malta and Greece.

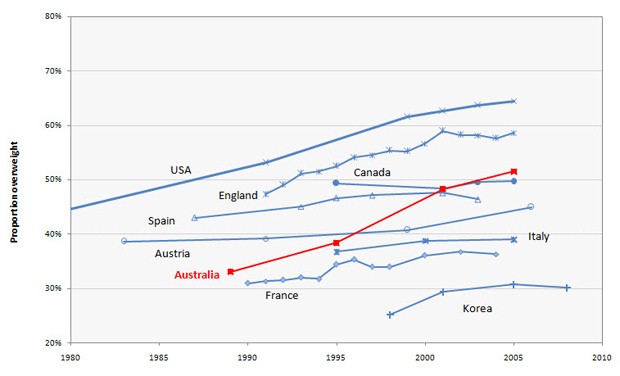

That doesn’t disprove the ‘sprawl makes you sick’ hypothesis of course, but it indicates there are very probably other factors at play beside residential density and car use. Here’s another study that should give further pause for thought. Obesity and the economics of prevention: fit not fat is an analysis by the OECD of the historical change in body weight of selected member countries (see first exhibit).

It’s immediately clear that England has a much higher proportion of its adult population classified as overweight than Australia. This was the case for the entire period studied by the OECD. Yet England has a higher average residential density than Australia. It’s also notable that even in 2005, Australia’s score was only marginally higher than Spain’s.

Australia has been an overwhelmingly suburban country for many decades. Despite that, we had a lower proportion of overweight people in 1989 than either Austria or Spain (or England, of course). Moreover, Australia ranked only marginally higher than Italy at that time.

While it might not destroy it, none of this sits comfortably with the “sprawl causes obesity” hypothesis. But there’s another aspect to consider, too. The OECD data tells us the proportion of Australians who were overweight in 1989 was 33%. By 1995 that had jumped sharply to 38% and by 2005 it had skyrocketed to 52%.

Those are phenomenal increases over a very short time frame. Yet they weren’t accompanied by an increase in car use on anything even approaching a comparable scale. Indeed, per capita travel by car in Australia over the period from 1995 to 2005 didn’t increase at all. Nor did residential densities fall massively over the period – multi-unit housing actually increased its share of dwelling stock. And note the OECD figures are for adults, so the rapid jump in fatness isn’t explained by the historical fall in the proportion of children who walk or cycle to school.

All of this suggests, at the very least, that caution should be exercised before asserting there’s a significant causal relationship between sprawl and body weight. The OECD study suggests non-physical variables might be far more important.

For example, Australian women with poor education are 40% more likely to be overweight than well educated women. In the US, African-American women are considerably more likely to be overweight than Non-Hispanic White women.

The 2011 Gallup-Healthways Wellbeing Index suggests the key factors that predict obesity in the US are race, income, age, region and sex. The best candidate for obesity is a low income, middle aged black man living in the South.

On the other hand, a twenty something, high income white woman living in the East or West of the continent is least likely to be obese. There’s a good chance she lives somewhere dense like Manhattan, Brooklyn or San Francisco, but that’s not why her body weight is healthy. She’d be slim even if she lived in the extensive suburbs of New York.

I think dietary changes provide a more plausible explanation than sprawl for the remarkable growth over 1989-05 in the proportion of overweight Australians. Like Chinese manufactures, fat and sugar got markedly cheaper in real terms in recent decades, both in the home and at fast food outlets. The dramatic fall over the same period in the proportion of households with a homemaker to prepare meals has also made cheap fast food an attractive option.

Sales of pre-prepared foods in supermarkets doubled from 1982 to 1992 and serving sizes increased spectacularly. Muffins ballooned to three times their traditional size; the most popular size of chip packets doubled; and soft drink bottles went from 200 ml in the 1960s to 375 ml, and, later, 600 ml.

That’s not to say that decline in physical effort wasn’t also a factor in the population’s weight gain, but I doubt we slacked off anywhere near enough to explain more than a small part of the extraordinary acceleration in body weight. Eating badly is simply a much more efficient way of gaining weight than abandoning light exercise like walking. For example, it takes a nine kilometre walk to burn off the calories in one KFC meal.

And to the extent less effort was a factor, it was much more generalised than just a result of sprawl. Driving is just one part of a continuum of “labour saving” activities that touch all aspects of our lives and have gotten dramatically cheaper with globalisation.

For example, more of us than ever live in apartments where we’re relieved of tasks like mowing the lawn, hanging the washing or cleaning gutters. Virtually anything in the workplace or home that involves effort can now be bought in a powered version at low cost. Remote controls are ubiquitous and we don’t have to turn keys to get in cars anymore! We don’t need to get up from our desks – much less leave the house or office – to do our banking, buy books or pay bills. And much more.

To many observers, though, it seems intuitively obvious that people who live in car-oriented places get less exercise than those who live in more walkable environments. Indeed, there’s evidence that residents of low density areas are heavier than those in denser areas, but as I’ve discussed before, that’s primarily a selection effect. Obesity levels in the inner cities of Australia’s major capitals aren’t lower than those in the outer suburbs because of higher density and lower car use, but because inner city residents are more likely to be younger, better educated, have higher incomes and not had babies.

It seems the difference in average weight between demographically similar populations at different densities is quite small. The reasons for that aren’t clear, but it might simply be that outer suburban residents spend more time on activities around the house, like gardening and home maintenance, than their demographic equals living at higher densities. Or perhaps the time they save by driving is applied to more effortful activities. It could even be that some inner city groups walk shorter distances than is commonly assumed.

I’m not persuaded sprawl is anything other than a minor player in the dramatic growth in body weight seen over the last 20 years in Australia. Now that doesn’t mean sprawl is a good thing. But if you hang the same villain for every crime you’ll end up letting the real perpetrator keep on offending. It matters for public policy that both the real causes of obesity and the real negatives of sprawl are properly understood.

Nor does it deny the possibility that if outer suburbs were positively designed to discourage car use that might help to reduce obesity. However that’s not a straightforward issue either but I’ll have to leave that discussion for another time, hopefully quite soon.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.