It turns out that the RBA has indeed (at least superficially) “misread” the economy, as so many commentators are keen to claim. Awkwardly, however, it seems to have materially underestimated the strength of our labour market, which its research suggests is the single most powerful predictor of future inflation.

Despite the RBA and Treasury forecasting that Australia’s jobless rate would rise to 5.5%, and using this as a key justification for lower rates (alongside a temporary decline in the prices of internationally traded goods and services), it appears, as I had previously argued, the peak in the unemployment rate is behind us.

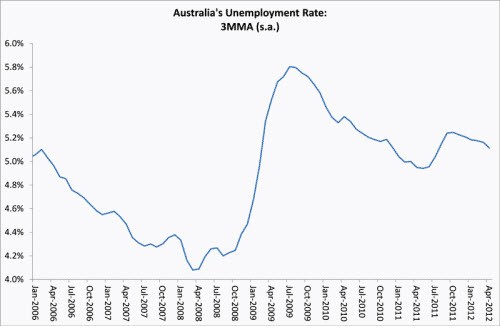

According to the official statistician, Australia’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate fell to 4.9% in April from a downwardly revised 5.1% in March. But let’s avoid the temptation of looking at a single month of data. As the chart below clearly shows, the three-month “moving average” jobless rate has been falling steadily since September 2011, ironically just before the RBA started slashing rates. It is now nearly a full percentage point below its 5.8% peak during the GFC.

The monotonic decline in the unemployment rate since the second half of 2011 tells us a few things. First, the economy is not about to head into a protracted recession. Nor is the economy likely expanding at a rate that is significantly below trend (or capacity). In fact, the jobless rate implies that the labour market is near-fully employed. This in turn tells us that the economy is not in dire need of further interest rate relief.

Having said that, the volatile and prone-to-revision GDP data could very well confuse the issue. As the RBA has noted, the National Accounts are difficult to interpret when the country is undergoing a very lumpy and capital intensive private investment boom.

The second thing the unemployment rate tells us is that the high circa 3.5% per annum domestic (or “non-tradable”) inflation consistently recorded by the ABS is likely to be a permanent presence. In contrast, the “tradables” deflation induced by the striking appreciation in Australia’s exchange rate is a temporary event. Indeed, with the Aussie dollar now down about 8% from its 2011 highs, the deflation in internationally traded products that helped pull down Australia’s core inflation rate will likely have the opposite effect going forward.

You are unlikely to hear or read many of these arguments from other commentators. Most analysts are forecasting an increase in unemployment combined with a lower cash rate.

Anyone with a commercial interest in the Australian equities and/or housing markets, including, importantly, almost all retail bankers, has been clamouring for rate cuts ever since the RBA appropriately tightened policy in November 2010. The Gillard government, its lobbyists and public proxies, are pinning their fragile political prospects on below-average lending rates. And the hysterical complaints of the trade-exposed industries almost always overwhelm the silent savers and retirees.

It is interesting to contemplate what the RBA might have done at its May board meeting had it had the benefit of this information and the Commonwealth budget. At face value, the super-sized 50-basis-point cut would have been off the table. And a single 25-basis-point reduction might have been a less than certain proposition.

*Christopher Joye is a leading financial economist and a director of Yellow Brick Road Funds Management and Rismark. The author may have an economic interest in any of the items discussed in this article, originally published at Property Observer. These are the author’s personal views. This material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment advice or recommendations.

What a joke!

Part time jobs grew and full time job fell, not exactly fantastic. Retails might have been up but services sector contracted as well as some others.

The AUD dropped to as low as USD$1.002 since the RBA cut rate giving not only consumers but many businesses the relief and confidence needed, and Westpac gave the full 50 points cut to business.

Rates are pretty much at the right level now. What is needed is the government, the banks & the RBA co-ordinate together, the banks can or should hold all rates and cut rate for business only and the RBA give that 25 basis point cut to keep more pressure on the dollar.

Yearly inflation fell to 1.6% out of target and core inflation at 2.15. The cut to lower the dollar and reduce the impact of the Dutch disease was well justified.