Jac Nasser’s lash at the government today stands as one of the more petulant pieces of rhetorical excess from the mining industry.

As Crikey explained a fortnight ago, business claims about the rising cost of operating in Australia have no foundation when it comes to the costs governments have most control over — wage pressures, via the industrial relations system, and tax levels.

Nasser insists there is something unbalanced about the industrial relations system that leaves “management being unable to operate its business in a fair and consistent way.” This is a furphy — the current Fair Work system mimics Peter Reith’s Workplace Relations Act on the extent to which unions can raise “management prerogative” as legitimate basis for industrial dispute.

Nasser does have a point about rising costs for the mining industry — but the issue is, whose responsibility is it? The industry is undergoing an unprecedented boom in an economy with minimal spare capacity. RBA deputy governor Phil Lowe provided some context for the industry’s expansion earlier this week. Mining and related activity grew by 12% last year and is expected to grow by a similar level over the next two years. That sort of growth invariably leads to cost pressures as the industry competes internally and with other sectors for resources, driving up the cost of labour (and the willingness of workers to engage in industrial action for better wages and conditions), the cost of business inputs and the cost of energy.

That’s one of the ironies of Nasser’s lament about high costs — his business benefits from high commodity prices for products such as iron ore, but concomitant with that is high energy prices, which increase the cost of his business inputs. Nasser, in fact, is fortunate that the strong Australian dollar has shielded BHP from the full impacts of higher oil prices over the past two years. And BHP, like all miners, has benefited from the way the high dollar, and the RBA’s willingness in 2011 to lift interest rates, has clobbered the non-mining sector of the economy.

In short, when Nasser complains about the high cost of mining in Australia, the guilty party isn’t in Canberra — or in Perth and Brisbane, where governments lifted royalty levels — but in his own boardroom and those of BHP’s competitors in the mining industry, who are driving the biggest ever resources boom in this country.

That’s particularly the case when you look at BHP’s own record when it comes to wasting money. There’s the losses of about $4.8 billion on the Ravensthorpe lateritic nickel project in Western Australia (and the associated refinery in north Queensland near Townsville, which BHP later sold to Clive Palmer, who has made good profits from it). Apart from mea culpas at annual meetings and investment conferences, BHP and its cheer squads in the media and business haven’t highlighted this botched investment. But it there has been a huge capital and opportunity cost for BHP.

And then there’s the $US26 billion the company has invested in the US tight shale gas businesses (gas and liquids). BHP has caught the top of this still expanding business that is changing the US economy. It has seen gas prices plunge as production has expanded (and the fourth warmest winter on record cut domestic gas use, which outweighed a rise in consumption by US power companies). BHP has changed tack and will boost production of liquids (which are light oil), but every other company in shale gas is doing the same and a glut has developed in the US oil market, which has seen prices there fall to less than $US92 a barrel (helped by the worries about Greece) while the price of Brent crude in London (is the major global marker price these days), has remained about $US109 a barrel.

Investors now widely expect BHP to take an impairment charge of several billion dollars on its US gas play (which could be reversed if prices improve in 2013, as forecasts suggest). But no one other than the management and board of BHP forced the company to invest so much money in the US gas business, just as no one other than the board and management has forced the company to invest so much in WA iron ore, and at such a rapid pace.

Rio Tinto, another moaner about costs, unions and taxes in Australia, is in the same position as BHP in iron ore: investing tens of billions of dollars to boost iron ore production and, with BHP, protect its market leading position in China and Asia as a huge, low-cost producer, before rival projects in Australia and elsewhere come on stream and threaten that dominance.

And like BHP with Ravensthorpe, Rio has a poor investment decision (a major blunder that almost ruined the company) in the $A44 billion buy of Alcan at the height of the first minerals boom in 2007, just as the GFC was starting. That excessive price is still holding back Rio’s productivity and profitability. It wrote $US8.4 billion off 2011’s record profit because of the fall in the value of its aluminium businesses (and some of its own assets owned before the Alcan buy).

No one is forcing BHP or Rio, or other companies to invest heavily in Australia. If there is a concern with costs and projects become uneconomic then they should be cancelled, deferred or restructured to protect shareholders (who, after all, own the company, not the board or the management).

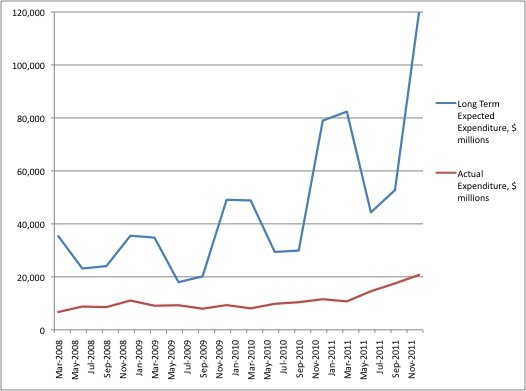

And there’s the rub — if a Labor government and aggressive trade unions are driving investors away from Australia as Nasser claims, where’s the evidence? Both actual expenditure and estimated long-term expenditure in mining have shown no signs of flagging since recovery from the financial crisis — not because of the mining tax, and not because of the introduction of the Fair Work Act, and not because of the carbon tax. The boom continues — to the chagrin of other, trade-exposed sectors of the economy.

If there’s some type of capital strike in the offing, as Nasser claims, there’s no evidence of it. Indeed, there might be more than a few large manufacturing companies who’d love nothing more than to see the back of some big miners, in the hope it might put some additional down pressure on the dollar.

It is clear from yesterday’s speech from Nasser, and a similar one in the US by CEO Marius Kloppers that BHP’s grandiose $US80 billion expansion plan is dead. No one forced the company to plan such a heady expansion, at such a huge, hard to grasp cost. It was a mark of the hubris that gripped the BHP boardroom and management suites, just as the rapid pace of expansion in iron ore in particular has been driven by desire to protect its market position. Rio’s act of hubris was the Alcan deal. Neither company and its management and board has yet owned up to admitting that many of the financial pressures on it are of their own making.

This is being compounded by a fall in global commodity prices for the third year in a row as Greece and the wobbly euro rear their ugly heads. You would have thought that last year’s re-run and the attempts by China to slow its economy would have forced the boards of both companies to pull their heads in. That is now happening, but just as Europe reaches a dramatic crisis and China’s bull run has slowed to a walk and could fall further.

Even though BHP and Rio are financially strong, their expansion plans have exposed them to significant financial pressures beyond their control. Blaming costs in Australia, or the state of the labour market here, or governments of either persuasion at the state and federal level, are strawmen. The problems are to be found at the top of both companies and the ambitious expansion plans of the two groups.

The whine industry – does anything whinge louder money?

Rinehart, Forrester, Palmer – Murdoch (vs the Left too), with his naggerphone?

sorry … the “whining industry”.

As a BHP shareholder, I wish Mr Nasser was more concerned at the hundreds of millions of dollars wasted on merchant bankers and the like on the abortive takeover escapades they’ve been involved in over the last number of years..

Nasser’s board is going to decide on capital investments of $30 billion this year alone. When people like him stand up and say that Australia is becoming a less attractive place to invest, it is smart to listen to what they say.

You can join Wayne Swan and write him off as a greedy billionaire miner if you like but it is likely that what he is saying is really happening and as the frenzy that is coal and iron ore prices eases, it is Australia that will flatten first while mining projects in Africa and South America continue to prosper.

Swan is utterly about the short term, as are you. Nasser is not.

That’s right David, Why would Jack tell us anything but the absolute truth?