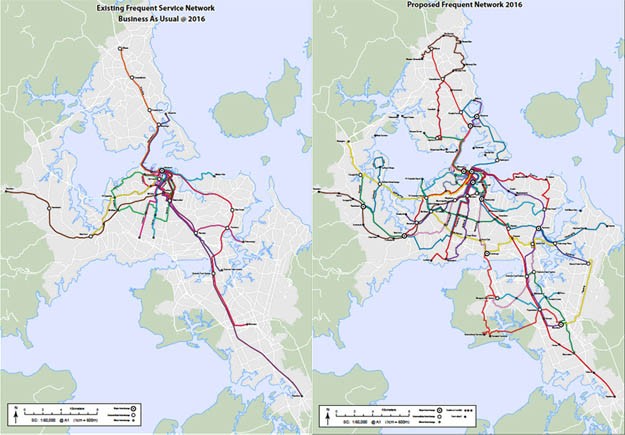

The first exhibit shows two alternative visions for Auckland’s frequent public transport service network (a service every 15 minutes from 7am to 7pm seven days a week). They’re from the Draft Auckland regional public transport plan via Jarrett Walker’s blog, Human Transit.

The one on the left is business as usual – that’s what it will look like in 2016 on current trend. The second is what Auckland Transport proposes it should look like in 2016.

The business as usual map is great for getting to the city centre if your origin is reasonably close to one of the transit routes. But it’s not much chop for going anywhere else.

The proposed alternative is an attempt to establish a genuine network. It conceives the entire public transport system as an integrated system rather than as a series of isolated ‘lines’.

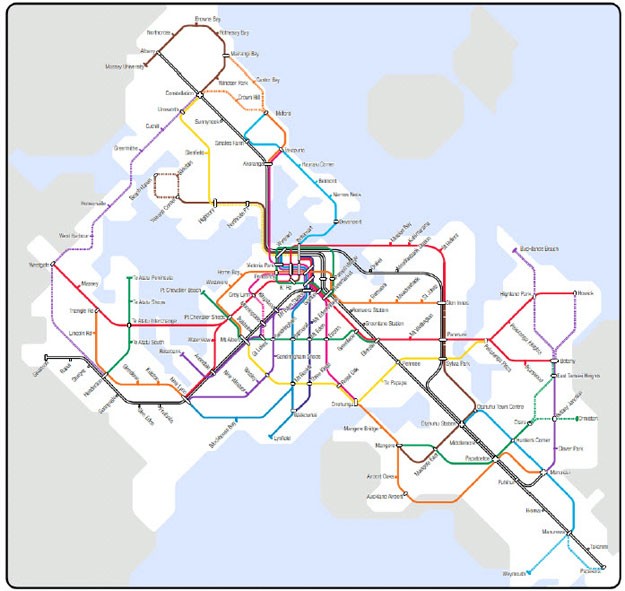

It offers greatly improved access to all of Auckland because it provides opportunities to connect to other routes at interchanges. It seeks to create a ‘synergistic’ public transport system – the ‘network effect’. The second exhibit (scroll down) shows the proposed network as a metro-style map.

The wonder is it could be up and running in four years and is claimed to cost no more to operate than the business as usual case. It replaces a complex historical accumulation of circuitous, low frequency bus services with a sparser grid that’s much more frequent and provides more opportunities for interconnection.

Transit consultant Jarrett Walker is involved in the project. He says:

The (proposed) network still includes coverage to all corners of the city that are covered now, and ensures plenty of capacity for peak commuters into the city. But meanwhile, it defines an extensive network of high frequency services around which future urban growth can organize to ensure that over time, more and more of the city finds public transport convenient.

Now compare this with the approach to improving public transport in Melbourne advocated by a transport expert, as reported in The Age. He says the Baillieu government should prioritise its “short list of really good rail projects.”

The projects he cites are the Melbourne Metro, an airport rail line and suburban extensions to Rowville and Doncaster. “What we need is a sense now of what is the formula that is going to deliver that suite of projects in a 10 to 12-year horizon”, he says.

This is not a lone voice. Much of the public debate about public transport in our cities has revolved around proposed new light/heavy rail lines.

Each of these projects has its virtues. Melbourne Metro is needed to address city centre capacity problems, although it’s arguable if it needs to be as big and costly as currently proposed. The others would all be ‘nice to haves’, but they take the majority of their patronage from existing public transport services.

The key concern, though, is they’d cost many billions of dollars and take many years – probably decades – to complete. Indeed, it’s unlikely the Victorian Government would commence more than one of these projects before 2016.

Moreover, they’d also add many fewer kilometres to the network than the kind of approach envisaged for Auckland. In fact it’s by no means clear that either Rowville or Doncaster, in particular, have been prioritised against alternative projects in terms of their potential to multiply the network effect.

What Auckland has in mind saves on capital costs by using low cost buses and, importantly, existing road infrastructure, to tie new and existing modes together via interchanges. Of course it’s not without its drawbacks.

Travellers aren’t used to connections. But as Jarrett Walker says, in the absence of connections the system will still have difficulty providing high frequencies.

As Aucklanders begin discussing the plan, I hope they stay focused on the core question: Are you willing to get off one vehicle and onto another, with a short wait at a civilised facility, if this is the key to vastly expanding your public transport network without raising its subsidy?

Another issue is buses aren’t as attractive to travellers as either light or heavy rail. Also, they often compete with other traffic and can get held up at traffic lights.

But they’re generally much cheaper and faster to establish than rail. A key requirement is they be given priority in terms of road use.

Over time, as patronage rises to a level that exceeds the capacity and/or cost-effectiveness of buses, it will make sense to consider higher capacity ‘mass transit’ options, like light rail or heavy rail.

What’s proposed for Auckland in 2016 is only the beginning. Longer operating hours, higher frequencies and a denser network would be better. There’s a map in Auckland Transport’s draft report that envisages a denser network in 2022.

Australian cities should have a good look at what Auckland’s trying to do. Their focus should be on a public transport network that increasingly gives users the option of travelling ‘anywhere, anytime’.

Buses and roads will have to be an important part of the mix because of cost and time constraints. Some rail will be in there but it needs to be prioritised on its systemic contribution.

Some of our cities have looming capacity problems, especially in the centre, that can only be addressed with rail-based solutions. But it’s questionable that projects like Rowville rail, which would extend the reach of the rail system further into the suburbs and draw patronage mostly from other public transport routes, should be among the leading priorities.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.