Australian voters love manufacturing protectionism. Forget what the econocrats, the commentariat, the Canberra elites, say on the issue. Nearly three decades on from the Hawke government commencing the winding back of automotive protection, voters are still all for governments propping up “real” industries like car-making.

But unfortunately for Labor, it’s not the sort of issue that shifts large numbers of votes. It’s not a 10th-order issue, but it’s not the sort of key issue, like economic management or health, that changes the way voters cast their ballots.

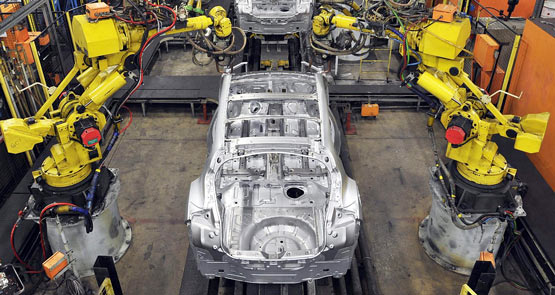

Nonetheless, Labor will press ahead today and commit yet more taxpayer dollars (bear in mind this is still the government; the caretaker period doesn’t commence until tomorrow afternoon) to the biggest, laziest parasites in the country, the transnational car manufacturers, one of which, General Motors, is currently demanding its workers take a pay cut to keep their jobs.

Worse, the funding is intended to leverage more state government assistance to Detroit and Tokyo, redoubling the impact on the public purse.

This will kick off Labor’s re-election pitch, as part of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s attempt to frame the election as the “new politics” of economic transition versus the Coalition’s “old politics” of negativity and personal attack. It might also offset the lingering impacts of the complaints of the salary packaging sector, which has been lamenting the government’s ending of the fringe benefits tax rort for novated leases by demanding the occasional bit of paperwork. The salary packaging industry had promised a mining industry-style campaign but has struggled to get any traction, despite calls for the workers of Australian to unite as they had nothing to lose but their late-model, fully imported SUVs.

But Labor was always headed for such a deal, regardless of any arguments about tax rorts, and despite the Australian dollar falling over 10% against the US dollar in recent months; Rudd, after all, has famously said he doesn’t want to be Prime Minister of a country that doesn’t make things, and propping up a small but visible part of the manufacturing sector fits with his campaign theme of a difficult post-boom transition.

Look a little closer, however, and the handout becomes problematic for reasons that probably won’t get a look-in from too many commentators, and not even from the usual critics of industry assistance.

Labor’s framing of the election as being about economic transition is more than just a campaign narrative. The forecasts in Friday’s economic statement back it up: the transition from mining investment boom to more traditional housing-led growth (and, eventually, a mining production boom, whichever side of politics is lucky enough to inherit that, given it will be a boon for the budget) is not going as smoothly as expected. Economic growth is softer than forecast in May, and unemployment will be higher. There’s a very real economic management question now about how much support fiscal policy should provide to the economy given interest rates can’t fall much further.

Labor’s trying to make the case that it is prepared to support a softer economy, by not offsetting declining revenue, delaying the return to surplus and weighting spending cuts and tax rises to the back end of Forward Estimates, while the opposition would slash and burn. It’s hard to believe shadow treasurer Joe Hockey would kick a struggling economy while it’s down, even if some commission of audit (businessman David Murray and The Australian commentators Judith Sloan and Henry Ergas, have you cleared your calendars for the end of the year?) thinks it’s a good idea — especially if Hockey knows that eventually a mining production boom should start pumping more money into government coffers. Nonetheless, in the absence of detail about Hockey’s fiscal plans, we can’t judge. But the sort of “support” that Labor is offering makes a mockery of its commitment to a stronger, more innovative economy: it wants to channel funding to a dying industry on which Australian consumers have turned their backs.

The Gillard government — hardly unbiased toward the automotive transnationals itself — had a more innovation-friendly approach earlier in the year, redirecting assistance away from big business and toward start-ups and small, innovative businesses.

The other component of Labor’s assistance is a commitment to make all Commonwealth-owned vehicles made in Australia. Normally government procurement decisions are made on the most cost-effective basis, but seemingly the Commonwealth will buy Australian no matter how much it costs. Strangely, you probably won’t hear too much complaining about this piece of voluntary protectionism in the media, even from those normally quick to berate Labor for a single taxpayer dollar wasted.

The implementation of both the USA/Australia and USA/China Free Trade Agreements resulted in an increase in the number of imported motor vehicle brands being sold in Australia. That surely was neither justified nor warranted by our relatively small population, and it has naturally affected sales of other long-established brands, including those locally made.

Another direct result of the US/Australia FTA is the amount of USA imported food being sold in Australia. That was also not justified or warranted as our farmers are more than capable of growing enough food to feed the population!

It is very weird – kill the car industry with fbt changes on one side then prop it up with handouts? Seriously if government wants to do something good for the country they should be subsidising electric vehicles – this country does have a competitive advantage in electricity production – instead it is just lining the pockets of Japanese and American shareholders.

The US/Australia FTA was always bad for us in all areas, good old John Howard again! Abbott is still going on about the FBT today, but I thought I read in Saturday’s Age that GM’s car sales are going up not down, so if so Abbott’s telling porkies again. Bernard, you seem to be so against supporting the car industry, but as Kim Carr corrected an ABC reporter this morning, there are heaps of other industries that receive just as much seemingly unnecessary support, mining for instance. It is hard to see how Hockey could ever gain as much revenue as he should with a mining production boom if he scraps the mining tax, another interesting one where the govt appears to be taking on the one hand and giving back with the other, courtesy of accommodating tax rules.

Bailing out Detroit is irony squared. The US home of auto making is bankrupt to the tune of US$20B. Just sayin’.

Rudd has turned on the desperate money fan back on, trying to buy votes, just like 2007