Whenever a city lucks onto something special – something that makes the rest of the world sit up and take notice – it’s natural to want to protect and sustain it and make it even better.

That’s reasonably straightforward when it’s something physical. Sydney’s blessed with a harbour, a bridge and an opera house and in recent decades has worked hard to ensure these priceless assets are looked after. It’s harder when it’s an event, but Melbourne easily found ways to fight off threats to its grand slam status.

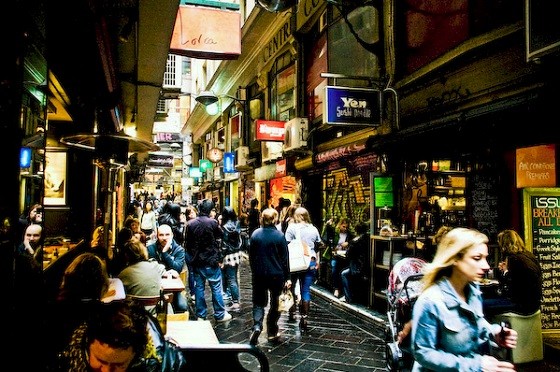

Where it gets really hard though is if the asset is something complex and vague like the sudden and dramatic rise in the international fame of Melbourne’s vibrant CBD and, in particular, its celebrated laneway culture.

Having gone from dead as a doornail a few decades ago to Frommer’s 2012 top-10 list of the world’s most walkable cities (not to mention numerous other hip accolades), it’s not surprising the citizens of Melbourne want to safeguard their fabulous city centre.

Writing in The Age last weekend, Guy Rundle argued that the character of lively urban areas like the north end of Elizabeth Street (he likened it to ‘scumble’) should be protected:

They can’t be preserved in aspic, but textural and social variety should play a role in how they’re developed, ensuring that rich urban life isn’t killed by concrete pours.

He says the richness of the centre should be tended with care because it supports the growing knowledge economy. Some reckon it has enormous value for tourism. Many just want it because it enhances their quality of life; it’s a key reason why they live in the city.

Protecting and sustaining the centre’s “buzz” against change is much harder though than preserving a Guggenheim or a harbour.

One reason is no one really knows for sure why Melbourne’s CBD flourished. If we don’t understand the underlying forces than it’s very hard to manage and maintain what might well be a very delicate flower.

Some put the blossoming down to the physical variety inherent in the Hoddle Grid of streets and laneways set down in the original 1836 plan for the city centre; others to the urban revitalisation initiatives of the Cain Government in the 1980s. Another explanation is the spirited work of the Melbourne City Council’s urban designers over the last 20 years.

It’s not one cause though. I think the Nieuwenhuysen liquor reforms are an important part of the explanation. So are other factors like the decline of manufacturing and finance; changes in tertiary education; the influx of foreign students; and more.

And it’s not just a matter of identifying causes. We don’t know what their relative importance is or how they relate to each other. We don’t know what the second and third order effects of each one is or what synergies, good and bad, they generate in combination.

Understanding the historical causes is hard enough; but grasping how the “buzz” might develop in the future is harder by an order of magnitude. It’s infinitely easier to pick out the threads in hindsight than it is to forecast accurately what will happen in the future.

Yet without an understanding of what drives the “buzz” it’s hard to know what might damage it and what might sustain and possibly even strengthen it. Public policy is replete with examples of well-intentioned initiatives that didn’t have the intended effect and in some cases had unforseen and undesirable side effects.

One of the key ideas in the Victorian Government’s new metropolitan strategy, Plan Melbourne, is to focus development on the city centre. That makes sense because relative to competitor cities like Sydney, Melbourne’s centre is more ‘elastic’ – there’s more scope for growth.

But how will more development impact on the city centre’s “buzz”? Some take it as given that new builds will be negative and others that the added activity will be positive. But we really just don’t know. There’s the risk of losing a prized asset; but there’s also the risk of foregoing a valuable benefit.

Given that they don’t really have much idea about the underlying engine, one argument is policy-makers should be extremely wary of setting down hard and fast planning rules concerning what kind of development is or isn’t allowed. They should proceed with a light hand lest their best intentions have a deleterious effect.

Yet on the other hand, unless a city is blessed from inception, it seems madness not to capitalise on a godsend when it materialises and move heaven and earth to keep it going. The sheer buzz of Melbourne’s centre is an amazing asset and it’s arguably now the city’s most distinctive characteristic.

The State Government needs a better appreciation of the value of the city centre as a cultural and entertainment centre, as well as a business centre. Both State and Local government need to put much more effort into understanding what drives and sustains the centre’s “buzz”; in particular they need to stop thinking of it as solely a design issue and start recognising the critical importance of non-physical factors.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.