If the Treasurer, Joe Hockey, raises the excise tax on motor fuel in his first budget tomorrow night as the strategic leaks indicate he might, there are two basic actions open to him.

He could index the excise in line with cost of living increases and get a delayed but continuing increase in revenue over the longer term. That would make amends for John Howard’s foolhardy decision to abolish indexation in 2001.

Or he could hike the current $0.38 per litre tax (possibly by three cents to $0.41 according to this report) and get an immediate increase in revenue.

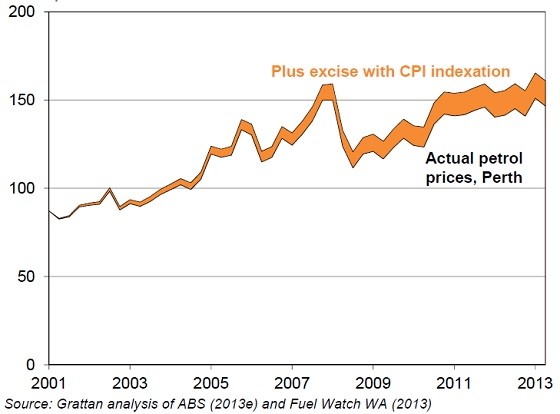

The Grattan Institute estimates the pump price of petrol would be 10% higher today (by about 15 cents per litre) if the excise had been maintained in real terms over the last 13 years. That would’ve had two positive outcomes: consumption would be a little lower and the Government would have circa $3 billion p.a. (net) more in revenue.

I hope the Treasurer announces at least one of these actions, preferably both, because increasing the fuel excise would be good policy. If so, I also hope the Opposition and the Greens temper their understandable temptation to reap political capital; and instead endorse the change.

It’s good policy because the public sector needs more revenue to finance expenditure. Further, while motorists arguably pay taxes and charges equivalent to what the Commonwealth and States spend on roads, they don’t pay the full social costs they impose in terms of pollution, noise and congestion. (1)

A higher rate of tax would give drivers greater incentive to make shorter trips and/or forego low value trips. It would encourage them to shift to more fuel-efficient vehicles and make alternative modes of travel like public transport relatively more attractive.

Although not as effective as congestion charging (which varies by time of day), the fuel excise is effectively a de facto road pricing policy. Those motorists who consume more, pay more. Economist Harry Clarke says it also “has moderate inefficiency costs because the demand for fuel is relatively price inelastic”.

As I noted when discussing the fuel excise a few years ago (What did abolition of petrol excise indexation cost?), the Productivity Commission observed in its 2011 report, Carbon emission policies in key economies, that the fuel excise effectively operates like a carbon tax, deterring people from driving.

Although it wasn’t put in place with the purpose of abating emissions, the excise already has a much more significant effect on driving than any level of carbon price that’s been seriously touted in political debate. The Commission calculated that in 2009-10:

fuel taxes reduced emissions from road transport by 8 to 23 percent in Australia at an average cost of $57-$59 per tonne of CO2-e.

Even though a modest increase in petrol prices looms large in the eyes of motorists, an increase of (say) five cents per litre wouldn’t impact significantly on the cost of driving. That’s because standing costs like depreciation, insurance, servicing, and charges – which owners tend to ignore when estimating the costs and benefits of a particular trip – dominate the actual costs of car use.

A driver who continues to travel the average 15,000 km p.a. in a vehicle consuming petrol at the average rate of 11 litres per 100 km, would pay an extra $82.50 per year if the pump price increased by five cents. That’s not a lot in the context of the $7,208 it costs annually – taking into account both fixed and variable costs – to run a popular ‘light’ car like a vanilla Toyota Yaris YR. (2)

As Professor Harry Clarke points out, any increase in the excise will inevitably be opposed by some on the grounds it’s regressive i.e. hits lower income motorists harder. But, he says,

What matters is the overall incidence of the tax-transfer system, not the equity character of a small part of the tax base. Of course the level of excise in Australia is low relative to excises in most European countries.

In any event, the Grattan Institute estimates the poorest 20% of households could be compensated for a rise in fuel excise if just 8% of the additional revenue raised was returned to them through the tax-transfer system.

If the Treasurer does increase the fuel excise, he’ll presumably sell it as financing new road infrastructure. Although the revenue isn’t hypothecated, higher expenditure on roads would make the need to find additional sources of finance more pressing so as to limit cuts in other areas.

Restoring indexation should be the easier policy choice because it only seeks to maintain the value of an existing tax in real terms. It thus side-steps much of the likely criticism on vertical equity grounds.

There’s a very strong argument though for supplementing restoration of indexation with a large one-off increase in the tax rate to claw back at least some of the ground lost over the last thirteen years.

______________________

- A 2009 study by Dr Garry Glazebrook estimated the social cost of driving at around $0.45 per km (at current prices)

- Or $8,315 p.a. for the ‘small’ Toyota Corolla Ascent; $11,157 p.a. for the ‘medium’ Toyota Camry Atara S; $12,423 p.a. for the ‘large’ Toyota Aurion AT-X; or $20,156 p.a. for the ‘SUV All Terrain’ Toyota Landcruiser GXL.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.