Benefits of the CBD and Eastern Suburbs Light Rail extension (source: TFNSW, CSELR Business Plan Summary)

There’s a common view that a key warrant for major public transport investments is the positive impact they’ll have on the rate of climate change.

In most cases though, the environment isn’t the main winner from big transport projects; even ones aimed at public transport users.

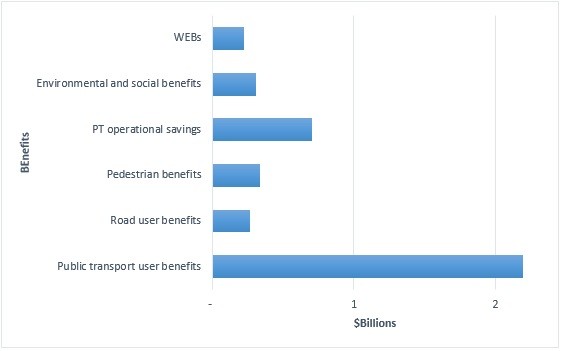

Consider the New South Wales government’s $2.1 billion CBD and South East Light Rail extension that will run from Circular Quay to Randwick and Kingsford. The business plan summary estimates the benefits from this investment will total $4 billion, giving a cost-benefit ratio of 1.9. The business plan cites a much higher ratio of 2.5, but that’s based on the original cost estimate of $1.6 billion. The cost was recently revised to $2.1 billion, bringing the BCA down to 1.9.

As the exhibit shows, it’s estimated more than half of all benefits from the project will accrue to existing and future public transport users in the form of faster, more comfortable and more reliable travel than provided by the buses they would otherwise use.

There are a number of other winners too. The new line is expected to generate operational savings and additional revenue for the public transport operator (i.e. the NSW government), as well as benefiting motorists through “decongestion” of roads.

Pedestrians will benefit from improved amenity, principally in George Street; and it’s assumed there’ll be wider economic benefits (WEBs) from more urban renewal opportunities.

However, the environmental and social benefits — which comprise reductions in emissions and air and noise pollution, as well as improvements in health — total $0.31 billion combined. That’s just 8% of the expected $4 billion in benefits.

Unfortunately, the summary business plan doesn’t separate environmental benefits from health benefits. However, it estimates the light rail service will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an average 23,300 tonnes per year over 30 years by replacing bus and (some) car trips. But even at a price of $100 per tonne, that’s only worth around 2 million dollars a year.

The decidedly modest payoff in terms of reduced emissions shouldn’t be a surprise. The light rail system will move many more travellers out of buses — another form of public transport — than out of cars.

It’s consistent with what other studies have found. For example, the feasibility study for the proposed Doncaster rail line in Melbourne concluded that 98% of forecast patronage would be diverted from existing public transport services.

Similarly, the feasibility study for the proposed 12km rail line to Rowville concluded it would increase the share of all trips carried by public transport in the metropolitan area in 2046 from 12.6% to just 12.7%.

The proposed Rowville line is forecast to reduce the number of car trips on a typical weekday in 2046 by just 15,000; that’s not especially impressive in the context of the circa 12,000,000 trips Melburnians currently make by car each day and the likely $4 billion or more cost of the line.

None of this means the CBD and South East Light Rail extension is a poor project. As I’ve noted before, the key rationale for it isn’t to reduce emissions.

Rather, the warrant for the line — which commenced construction last week — is based on traditional transport and planning objectives, particularly increasing public transport capacity and improving the amenity of the CBD. The reduction in emissions is of course welcome, but it’s a long way from being an important justification for this, or most, urban public transport projects.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.