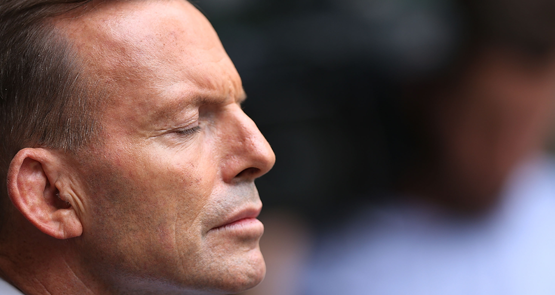

A few more days of good government like yesterday and Tony Abbott will be history. And, again, the problems are entirely self-generated. Let’s recap:

- Abbott called a report showing, among many other horror stories, that there had been 33 separate incidents of sexual assault of children in Australian care “blatantly partisan” and said the body that produced the report should be “ashamed of itself” — the sort of response that used to characterise Catholic objections to criticism of its handling of paedophiles, when it would claim sectarian victimisation;

- Revealed information about the case of two Sydney men charged with planning a terrorist attack that police had previously refused to release, potentially endangering the chances of a conviction of the men;

- Completely overturned his previous approach of seeking bipartisanship and a “Team Australia” approach to the national security with a deliberate strategy to try to link Labor and its asylum seeker policies with one of the suspects;

- Again failed to explain what process the government would now use to determine the construction of the new Royal Australian Navy submarine fleet, insisting the whole thing was Labor’s fault anyway;

- Boasted about breaking his commitment to not cut funding to the ABC, saying “frankly, it is just as well we did”;

- Failed to articulate what the government’s economic strategy was on the day unemployment surged to a 12-year high; and

- As a kind of rhetorical grace note, accused Labor of being responsible for a “Holocaust” of jobs.

It’s clear that Abbott’s path to turning around his leadership lies in aggression — not merely at Labor, but at anyone perceived as not on the government’s side, like the Human Rights Commission or the ABC. This was the path he flagged after he survived last Monday’s spill motion when he boasted of his capacity to fight Labor and asked to be allowed to get on with doing that.

But in style, it represents a doubling-down, not a change of direction. It was Abbott’s aggression that exacerbated the government’s problems last year: his refusal to accept criticism of the unfairness of the budget and his insistence it was an example of the “fair go”; his refusal to accept that he had broken election promises; his attack on critics of Peta Credlin as sexist; his attacks on the ABC; and most of all his stubborn refusal to accept any need for change until he came within a handful of votes of having his leadership spilled.

Out of all the criticisms of Abbott made by his enemies, his opponents, commentators, his ministers and his backbenchers over the last 17 months, the lament that he is not being sufficiently aggressive has rarely featured among them. Aggression is, famously, Abbott’s native state. As a media adviser he literally shaped up to journalists; as an MP he would challenge dinner-table interlocutors to step outside; as a junior minister he gleefully played the role of John Howard’s attack dog; as opposition leader he brilliantly tore down two prime ministers — one of them twice.

As prime minister, though, aggression isn’t enough; if anything, it can be counterproductive. The best leadership teams have a leader above the fray and a ferocious deputy who does the attacking. Aggression contains within it possibility of going too far; overstepping is an occupational hazard of the attack dog, and when the prime minister is the chief attack dog it means he ends up having to apologise, as Abbott did yesterday.

Keating, of course, was his own attack dog, but voters also knew it was in the service of a political and economic vision. To the extent that voters think they know what Abbott’s political and economic vision is, they don’t like it. And it’s not clear more aggression is going to change that. but who knows, perhaps “good government” will start next week.

“To the extent that voters think they know what Abbott’s political and economic vision is, they don’t like it.”

The corollary of “born to rule” is “born to serve”.

And the latest breaking story about the AG asking for Gillian Trigg’s “resignation” is yet another ticking bomb.

Much as I realize what a gift DumDum is to Labor I really wish they would all go out in a DD ASAP.

And Labor might think long and hard about Shorten.

We’re perhaps fortune Abbott doesn’t read Crikey regulars’ posts. If he did, imagine how much senseless “agro’ he might have absorbed from them.

I think you’ve nailed it, BK.

You forgot about the implication that the two recently arrested terror suspects being allowed into the country was ‘Labor’s fault’ (courtesy of Dutton).

It it true that this is Abbott’s preferred state of play but it’s pretty risky given his own reliable talent for going too far or saying something ludicrous and the fact that the other’s in the government who are not as ‘practiced’ at the art will likely stuff up regularly too.

And the man who can execute the tactic with real wit and class is Malcolm Turnbull, but I guess he wants to be careful not to be seen to be too close to Abbott.

This is clearly a guy with no ‘plan B’. He’s like the drongo Australian tourist when confronted by another language: speak slowly and clearly (and patronizingly). When that doesn’t work just ratchet up the volume.

On balance perhaps it would be better if the pre-Good Government Starts Today version of Abbott made a return.