It’s always exciting to be quoted, as a critic, even if it’s just in the publicity material for an artwork you’ve reviewed. Although most critics will fiercely defend their position as being outside the marketing “ecosystem”, we’re usually more than happy for publicity departments to use our words and names if it will help to sell tickets for a show we believe is worthwhile. That is perhaps the greatest joy of arts criticism — that you’re able to make recommendations to a wide audience and support the work you love.

But surprisingly frequently you find that you’ve been quoted in advertisements or other publicity materials for a work you reviewed negatively. It first happened to me in 2013, following a generally negative review of Sydney Theatre Company’s Fury (don’t let the star rating mislead you), in which I had positive things to say about Andrew Upton’s direction and the acting, but not much for Joanna Murray-Smith’s writing. If you look at the STC 2013 annual report, you’ll see that my one positive paragraph has been expertly excised and published under “what the critics said” on page 26. It struck me as a pretty odd choice, considering there were many more effusive reviews of Fury than mine and it’s the only instance I was quoted on that page, despite reviewing many other plays more positively over the course of 2013.

But it’s a fair representation of what I had to say about Upton’s direction — just an example of selective quoting.

Where things start to get misleading, and where critics start to get cranky (and I assure you, “cranky” isn’t the status quo for most of us), is when words have been twisted in some way, beyond their meaning, and taken completely out of context.

Adelaide-based critic Jane Howard reviewed The Darkside at Adelaide Film Festival in 2013 and from the sentence “and yet the series of monologues fail to come together as a compelling feature film”, the word “compelling” was cherry-picked and used in advertisements. Single words are highlighted out of context all the time — when Vicky Frost reviewed Melbourne’s King Kong musical for The Guardian, she wrote: “Kong himself is magnificent, and there is exciting and innovative theatrical imagination on show. But uneven storytelling and a patchy score means this musical punches well below its considerable weight.” The pull quote? “Magnificent”. I can’t recall if the publicity department applied an exclamation mark to make it “Magnificent!” in this instance, but the magically appearing exclamation mark is a pretty standard tool of the trade. Professional critics don’t use that many exclamation marks, if you hadn’t noticed. (Despite the one in this headline!)

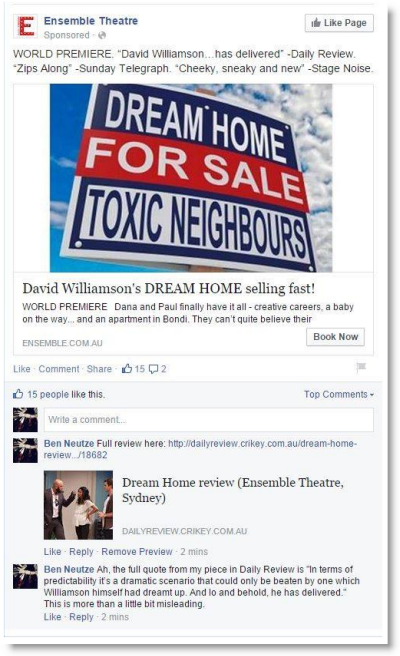

But then a week ago, this happened, following my review of David Williamson’s particularly underwhelming new play Dream Home at Ensemble:

I didn’t point out how misleading it was because I’m particularly worried about being misrepresented — I’m more concerned that audiences may be misled by the practice.

To Ensemble’s credit, its PR team quickly changed the quote on their Facebook post and picture so as to attribute it to ArtsHub’s Gina Fairley, but the new version is potentially even more misleading. The full quote from her review is: “Williamson has assembled and delivered this lazy string of characters with comic zeal.” The “sell” at the top of Fairley’s review reads “David Williamson’s new play hits the popularist button but fails to deliver.” That’s rather at odds with “Williamson … has delivered”. And you do have to wonder exactly how far they would have gone. If I’d written “David Williamson has not delivered”, would the pull-quote have been “David Williamson has … delivered”?

There are some pretty extraordinary examples of such behaviour overseas. Guardian critic Michael Hahn found his words on a big sign outside the West End theatre housing Rock of Ages in 2012. From his one-star review, which read: “It’s a very peculiar show indeed, with an unvarying and unpleasant tone of careless sexualisation. Rock’n’roll debauchery is presented as the pure and innocent way of dreamers”, the words “Rock’n’roll debauchery” had been extracted and splashed across the side of the theatre.

Just a few years earlier, in 2009, another London theatre became the first to be investigated by Westminster Trading Standards for misleading quoting. A sign for the theatrical version of The Shawshank Redemption playing at Wyndham Theatre read: “a superbly gripping, genuinely uplifting drama”. Unfortunately that quote, from Charles Spencer in The Telegraph, was referring to the 1994 film. Of the stage version, he wrote: “I would suggest that your cash might be better spent elsewhere. The DVD is being sold for just 2.98 pounds on Amazon, and yesterday a Sunday newspaper was giving it away. In the West End, by contrast, you will have to pay 49.50 pounds for a top-price ticket — though there are seats in the gods going for a tenner. In almost every respect, however, the stage version is inferior to the movie.” The maximum penalty for trading standards offences in the UK is two years in prison, which the producers managed to avoid.

The practice happens just as frequently for movies. Gelf Magazine published a list of The Best Worst Blurbs of 2007 from the film industry, which featured Jack Mathews of the New York Daily News, whose review of Live Free or Die Hard featured the sentence: ”The action in this fast-paced, hysterically overproduced and surprisingly entertaining film is as realistic as a Road Runner cartoon.” The pull quote? “Hysterically … entertaining.”

Should theatre companies and other arts organisations stop selective and misleading quoting? Should they be locked up if they do work to mislead an audience? Or do audiences now just assume when they read “Extraordinary!” in an advertisement, the critic might have just been referring to the lighting design?

*This article was originally published at Daily Review

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.