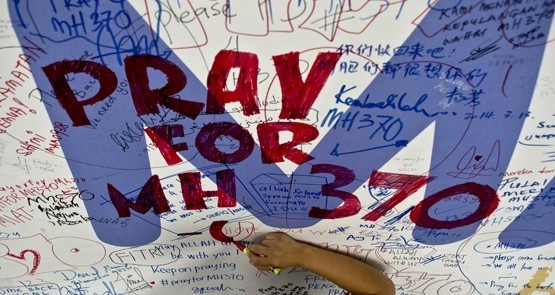

As the second phase of the search for missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 enters its final days, the issue that seems to tower above all is that the Malaysian government hit the ground lying on March 8 last year, even before the flight had exhausted the fuel it was carrying for its early morning run from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing.

The Malaysian government has not had the fortitude or decency to explain its duplicity, and our government has not had the guts to publicly query this either. Do we have to wait a few decades for the release of the cabinet papers?

The US knew within a week of the flight disappearing that it had crashed into the Indian Ocean west to south-west of Perth. It said so through its White House spokesperson, possibly through frustration with the narrative being inconsistently peddled by Kuala Lumpur.

But did the US know this from its own observations from satellites or shipping, or did it know from the Inmarsat “pings”, which indicated the flight had turned south sometime after recrossing Malaysia and flown into oblivion in the Indian Ocean?

These and many other questions dog the search for the jet. The search team is supposed to complete its deep-sea scanning of a priority zone of 60,000 square kilometers by the end of this month, and then, barring a last-minute discovery, move into a similarly sized second-best priority zone surrounding the current area of prime interest.

To understand why there are concerns that a massive cover-up is being perpetrated over the loss of MH370, consider the sequence of events.

The initial search, in Australia’s designated oceanic search and rescue zone, was aerial, and involved aircraft from many countries, soon supported by shipping, particularly from China, Malaysia, the US and Australia, as well as a cameo appearance by a British nuclear submarine, which for some reason or other was in the vicinity and then vanished from the news within days.

The sea-surface search was largely targeted by estimates as to how far floating wreckage would have moved from likely impact points and strongly guided by satellite imagery indicating what might have been debris from the jet.

No sooner had radar satellite imagery recorded solid, floating objects than the search was pulled in what seemed like undue haste to the north-east of that area, even though aircraft had also made some unresolved sightings of objects.

Malaysia was then, as it is now, the party calling the shots as to search priorities.

That first phase of the search looks quite odd with the passing of time, although as more shipping became available, the focus was naturally on picking up any acoustic pings that should have been emitted by the 777’s black boxes from the sea floor for at least a month.

Acting on the world-leading skills of the Royal Australian Navy’s acoustic analysis laboratory in Jervis Bay, search leader Angus Houston and Prime Minister Tony Abbott made what with hindsight proved to be recklessly optimistic assertions that Australia had found the plane.

Those acoustic signals were not from MH370. Nor were those detected some distance from the Australian discovery by a vessel from China.

This led to the current second stage of the oceanic search for MH370. This includes a 200,000-square-kilometre bathymetric survey of the otherwise mostly uncharted sea floor, which is more than 6000 metres deep in some places.

Once its obstacles and depths were known with precision, the 60,000 square kilometres that were thought most likely to contain the heavy part of the wreckage were then imaged with towed sonar scanning platforms.

These were backed up by a large autonomous underwater vessel that could resolve in fine detail anything the looked suspiciously like parts of MH370 to the scanners. Concerns that MH370 may have been scanned but not recognised were allayed by the recent discovery of a what looks like a 19th-century shipwreck in the search zone at a depth of almost 4000 metres.

But the southern Indian Ocean is a massive place, and the calculations and assertions used to predict just what path MH370 flew before it ran out of fuel have not yet produced the goods.

It is possible that parts of the floating wreckage might also remain undiscovered along the southern Australian coastline, or over in Chile, or western Africa, or one day Cornwall.

The lies about what the Malaysia Air Force saw, or didn’t see — and the excuses made by the airline to the Vietnam air-traffic-control system about the path that MH370 flew — reflects exceedingly poorly on these parties.

The behavior of the airline and its government and its relevant aviation and defence authorities are reason to believe that answers as to what happened to MH370 might be more readily found in Kuala Lumpur than in the pitch-black depths of the southern Indian Ocean.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.