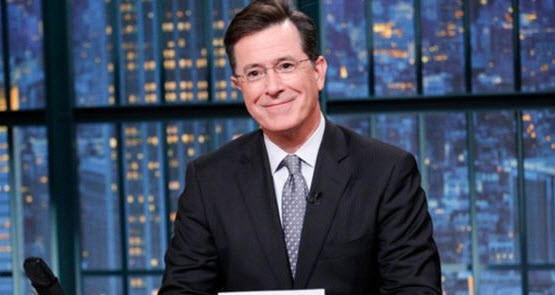

Well, it’s happened. Tuesday night in the United States, Stephen Colbert, minus the slicked down, side-parted conservative-do, strode out in front of the audience at the Ed Sullivan Theatre to the music of post-jazz supremo Jon Batiste and started a new and brave era of late-night TV. Really? No, of course not. But he certainly shut the door on an old one.

Colbert has taken over the slot vacated by David Letterman, who retired after more than 30 years on The Late Show, thus ending his own Comedy Central 11.30 show The Colbert Report at the same time as Jon Stewart left The Daily Show. Red-eye for those who don’t want to admit that the day has ended — and for a while there was a third one, Last Call, with Carson Daly, which went out at 1.30am to god knows who. Jay Leno had already set the process in motion by departing from The Tonight Show — for the second time — after leaving to start up a prime time talk show, and leaving the hosting duties to Conan O’Brien, the former Simpsons writer, who proved too much of a cold fish for the lot and moved to TBS, a basic cable station, the sort of Motel 6 of basic cable.

Should the reader wonder why I am reciting these details like a chronicle of Sumerian kings, it is, well, it is out of pure pain. With the Leno-Letterman-Stewart-Colbert quadrella, late-night TV had got about as good as it was going to get. You started on Stewart or Leno at 11 or 11.30, switched back and forth, went to Letterman for the monologue at half-eleven then to Colbert and back for the last part of Letterman. Or you watched Leno and Letterman through, and then watched the 1am repeat of Stewart/Colbert. The ad breaks were two minutes, so there was plenty of time for sex in between, for both Americans and Australians, am I right ladies?

It was an urbane and civilised rounding out of the day, the talk show one of the great American cultural creations, along with jazz and Hollywood, one way among many to do TV that came to seem the only way. The urbanity, in a culture that was fast losing the right to be called by that name, was due to the timeslot — for all the fuss around these shows, their viewing numbers were small even in the great days of network TV, and smaller still after the basic cable explosion of the early ’90s, when Americans suddenly got access to 50 or 60 channels at a time.

A matter of a few million people in a land of 320 million were watching. Most watched Leno, the successor to Johnny Carson, his monologues dumbed down and obvious, his interviews fawning free publicity for a sushi-train of stars major and minor.

Letterman is often supposed to have started the alternative late night show, suited to a college-educated crowd, emerging into the workforce in the ’80s and eager for something to watch. That’s true, up to a point: in fact the pop-culture polymath Steve Allen had “deconstructed” the talk show as early as the ’50s, jumping into giant vats of custard, and featuring the Hollywood eccentric “Gypsy” Bootz (the man about whom the song Nature Boy was written), who would swing into the studio on jungle vines. Letterman routinised it, to the degree that by the 2000s it was deadened irony, watched in that spirit by a generation now in on the gag (college-debt-mortgage-job-mall). Most Americans went from one year to the next without tuning in, or being up late enough to have the option.

That gave the talk shows a freedom they would have lacked in prime time. When Leno tried to move to a pre-1opm slot, the show failed. In the days when people were still watching scheduled TV en masse, they wanted something else, and Leno slunk back to late-night, pushing out Conan O’Brien. His TBS show sometimes goes out to a few hundred thousand people, making one wonder why on earth he bothers, the answer to that question being, because it’s a TV show. Once you’ve done that, why would you want to do anything else? How could you? But now the question is, how can anyone?

The truth is that the talk show per se was in trouble as soon as Letterman put the ironic and self-parodic element front and centre. To base a whole show around a recurring segment of throwing watermelons out of an eighth-floor window is funny because you’re watching it because it’s on TV.

Those sorts of meta-moments bled through in Carson, or earlier and now forgotten shows like Jack Paar, but their impact was maximised by the show being played straight. The humour wasn’t about the absurdity of being on TV; it was about what Orson Welles said to Barbara Bel Geddes, before a stand-up routine by Joan Rivers. Today, it’s possible to exaggerate just how urbane Carson’s show was — most of the guests were actors — but it was a place where, some nights, Gore Vidal would appear sitting next to John Gielgud. With a song from Charo. The show had a command you couldn’t fake today. Judged by old episodes it was also frequently more than a little tedious. You couldn’t say that about Letterman.

What you could say is there isn’t much elsewhere to go after him. Seth Meyers, replacing Jimmy Fallon on NBC’s late night show, after Fallon replaced Leno, has made his show the most arch and catty of all the offerings — and hence the best of them.

Colbert’s opening show had to go meta-meta, featuring the network head in the audience, with a big switch ready to turn over to a re-run of The Mentalist if things were slow, and Colbert and George Clooney doing a non-interview because the latter had no movie to plug. The house band is Stay Human, a sort of deconstructed jazz outfit, playing with the whole idea of the super-tight show band — inch-perfect musicians playing sprawling overflowing tunes, in a mix of costume bottom-of-the-laundry basket gear. The hipsters have taken the heights of culture.

Good enough for a first show — as Colbert said, he had nine months to make it — but where to from here? Jimmy Fallon has taken on the challenge of succeeding Leno by all but doing away with the talk altogether, in favour of sketches, stunts and moments. That leaves Colbert as the more traditional offering. But it also leaves one with a sense that the talk show, whatever it was, however good it was, was a product of a genuine mass culture, where 40 million people a night could be watching the one show.

The talk show presumes that an amphitheatre spreads before it endless, filled, and to the horizon. When that has been broken up and a thousand small scenes contend, who is doing the talking? And who the listening? And what will I do with my late nights now?

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.