Stable stability? The Reserve Bank’s second report for the year on financial stability is out on Friday, and everyone will be reading it for what the central bank says about the impact of the housing booms in Sydney and Melbourne on the stability of the financial system generally. Last Tuesday’s post-board meeting statement from governor Glenn Stevens didn’t refer directly to the report, but it was extensively discussed at the meeting.

But you can get an idea of what the bank currently thinks of the dangers from the some comments in Stevens’ October statement: “Regulatory measures are helping to contain risks that may arise from the housing market.” That was a change from what he said in the September statement: “The Bank is working with other regulators to assess and contain risks that may arise from the housing market.” That was also the comment in Stevens’ March statement, which discussed the first financial stability report of the year. The change in wording this month is a clear sign the bank and the other key regulator, APRA, believe the measures to tighten controls on investor lending are starting to work and will reduce risks over time.

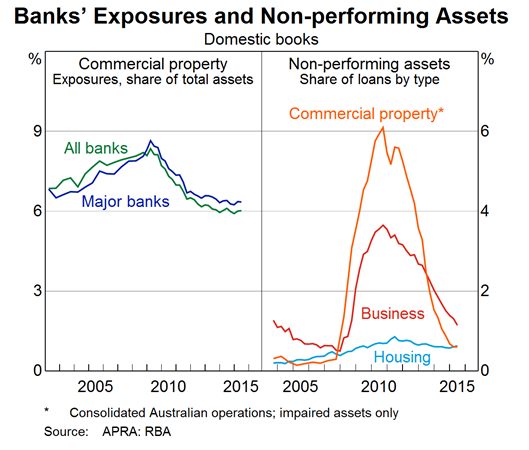

But we should understand that even though household debt is high at a worrying 180% of GDP (because of the surge in housing loans to buy or build, in Sydney and Melbourne especially), home lending is not the area of property where danger to the financial system and the wider economy comes from. That is commercial property lending. — Glenn Dyer

It’s uncommercial commercial. That was a point made in a speech early last month from Luci Ellis, the head of the Reserve Bank’s Financial Stability Department. She is one of the bank’s experts on property prices, property demand and their impact on the financial system and financial stability. That is why she was headhunted from the Bank of International Settlements, where she had built a reputation in the areas especially on the subprime mortgage crisis and aftermath in the US. She is not a worrywart about our house price boomlets in Sydney and Melbourne, but she does recognise (historically) the dangers to the economy, banking and stability from commercial property lending. Ellis said in her speech on September 10:

“Another thing we risk forgetting is that property markets are not just about households’ mortgages. Property development, including for residential property, and commercial lending related to property more generally, should also receive sufficient attention from risk managers, policymakers and academic researchers. It is these segments of lending that tend to grow in importance in the late stages of a boom, and to account for a disproportionate share of loan losses in a bust.”

“And if we are looking for surges in credit growth as precursors to painful downturns, we should bear in mind that, historically, these surges have been evident in business credit far more than in housing credit. That is certainly what we see in the Australian data … If you look at the right hand box you see that in the most violent credit event in Australia since the recession (and probably since the credit squeezes of 1974 and 1960, commercial property and business loans went belly up at a much larger rate than did housing mortgages.”

“That’s not to say that this time housing mortgages would create a problem — if the credit event is violent, there will be a jump in souring loans and losses for lenders. But you have to differentiate between the commercial lending to residential developers (housing and especially home units) and the mortgage lending to the buyers of their apartments and home units. And lending on city office blocks or business parks in the suburbs, or on shops and shopping centres is different to lending to home owners.”

— Glenn Dyer

Budgets can hit mortgagees. But Ellis had an additional warning — the unintended impact of public policy changes on mortgage lending of all types:

“We don’t only risk forgetting that property is not just about home mortgages. We also risk forgetting that these different market segments are not all the same as each other, or across countries. Institutional settings and public policies affect credit risk greatly, sometimes in ways that are not obvious. There are clear connections between financial stability outcomes and the mandate, powers and culture of the prudential supervisor, or the form and coverage of consumer protection regulation around credit. But it is perhaps less obvious that labour market institutions, for example, or the way health care is paid for, can affect the idiosyncratic risks households face, and thus the credit risk they pose to lenders.”

A health policy change, a rise in the Medibank levy, a paid rise in road tolls and a surge in petrol prices can impact the incomes of mortgagees and therefore risks to lenders of all types. It is estimated that nearly half all mortgages are being repaid faster than they should be (mortgagees are repaying at interest rates far above their standard rates). That’s an added comfort for lenders and regulators and ignored by the Hennies Penny among the commentariat. No company does that because it would reduce profits and bonuses to executives and boards of the borrowing companies. — Glenn Dyer

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.