This morning they were nibbling on the little sandwiches at the new ASIO headquarters in Canberra and listening to the polite speeches this morning at the launch of The Protest Years, a history of ASIO form 1963 to 1975. Exciting years, because they cover the period when the world rose up against Western imperialism, in South America, Africa and especially Asia, which is what concerned us most. In the post-World War II years, Australia had had a mildly favourable attitude to decolonisation, as long as it concerned empires other than the British. But that rapidly turned when the new third-world order turned to state socialism, seen as the obvious mode for decolonised countries to adopt. While communism was constructed as the official challenge, state socialism (with varying degrees of democracy) was almost as much a threat, because Western economies were relying on cheap raw materials, and also expanding markets in those areas. We were dutiful partners to US enforcement in all this, actively aiding the 1965 coup in Indonesia, which resulted in the “politicide” of between 500,000 and 1 million people (at least), we trooped off to Vietnam, and we supported apartheid South Africa with only the mildest of criticisms.

ASIO was dutifully obedient in all this, dutifully anti-democratic in its surveillance of domestic dissidents — people like Keith Windschuttle, Paddy McGuinness and Christopher Pearson. I wonder what happened to them. As well as those bogus misfits, it also kept book on genuine activists. Gary Foley was one of the first people to request his ASIO file on the 30-year rule, thus getting a new instalment on his past life every January. Volume-wise, the file is — well, it has its own room at Victoria University of Technology. ASIO was also studiously resistant to monitoring right-wing violence in Australia — especially groups opposed to the socialist government of Yugoslavia, which had kept peace in the Balkans for 30 years. Their willful ignorance of Croatian right-wing Ustasha plots would ultimately result in the only major terror attack on Australian soil — actual bombs –in Canberra in 1972.

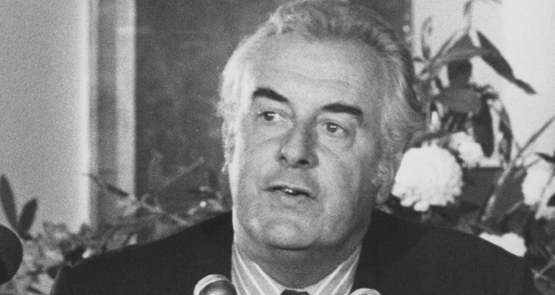

By that point, we have always presumed, ASIO was acting as a small version of a “deep state”, doing the bidding of the US at a time when the Whitlam government had started to refuse and resist US intelligence co-operation. Whitlam was far from a political radical — he was pretty slow to condemn the Vietnam War, especially compared to then-ALP leader Arthur Calwell, who condemned it as a “racist, imperialist war” — but he was still part of a global post-war left, in the way that future Labor leaders would not be. When the Nixon administration and the CIA backed a coup against the democratically elected Marxist Allende government in Chile on September 11, 1973 (after years of fomenting it), the Whitlam government began to withdraw active intelligence co-operation. But we have always suspected that ASIO didn’t — and now apparently, in the new official history, that is made clear: intelligence-sharing continued against government instruction, a situation that would ultimately lead to attorney-general Lionel Murphy raiding ASIO HQ in 1974 (thems were the days) — and ultimately to the executive coup of November 11, 1975.

Author of the official volume John Blaxland now says there is “circumstantial” evidence that the CIA and Ford administration was involved in the ’75 coup. Well, we’ll see what he means by circumstantial when we get the book, but there has been a wealth of evidence lying around before, most comprehensively covered in John Pilger’s A Secret Country. Given what we do know — from CIA leaker Christopher Boyce and other sources — the idea that US assistance in knocking a Labor government over was “circumstantial” is pretty risible. The US-backed Allende coup was not without personal interest for a Whitlam Labor government. After all, Allende had appointed Pinochet, his ultimate executioner, as a way of putting a “centrist” figure in power, as a mediation with forces that be. Whitlam had done the same thing with John Kerr, a one-time Trotskyist (in the late 1940s), who had made a rapid transition rightwards, becoming a stalwart of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA front-group whose tentacles spread throughout the Western world. With the Nixon-Kissinger administration on the war path against “enemies”, Whitlam realised that he was in a far less secure position than he might have believed. He was right.

The 1975 coup was a soft version of the 1973 coup — made softer by Whitlam’s decision not to take any number of actions (such as refusing the dismissal and sacking Kerr) that might have led to open conflict. Both were at the end of an era that was beginning to close up. The more significant was the Chile coup, because it not only closed down a dissident government, it brought in a dictatorship willing to impose the Friedrich Hayek-Milton Friedman vision of what was not yet known as “neoliberalism”. Such a reversion to the power of capital could only be imposed by dictatorship, for all that it appealed to notions of freedom.

Interesting it was done at a time when Chile was experimenting with more freedom, not less, as a socialist economic strategy. Supervised by UK management guru Stafford Beer, Chile’s “cybersyn” network used mainframe computers to model the economy using real-time feedback from factories and departments (using telex machines!). The aim was to create a flexible socialist system that responded to information from scattered economic points faster and more efficiently than the market could — thus refuting classical liberalism’s most serious charge against socialism, that it could not respond to real-time economic shifts. We don’t know — and may never — to what degree a coup was staged in favour of capital, not because socialism was failing, but because it was evolving and meeting new challenges.

And we will await our copy of The Protest Years with interest. We have a lot more to go on than official histories these days — the 2.4 million-document library of the WikiLeaks “PlusD” library, which might give an alternative account of the events of the time. Although we have no doubt that Blaxland, despite being the official historian, will have been rigorously critical of an organisation that appears to have spent less of its time defending Australian democracy than it did nibbling away at it. Nibble, nibble.

Ah, memories…

What I wouldn’t give to see all those heads exploding,

if we could magically replace George Brandis with Lionel Murphy.

Yes indeed Paddy – if you think we live in interesting times now….think again.

Only the terminally naive believe that the operations of the ‘deep state’ have in any way diminished. Peter Dale Scott among others have documented its fundamentally undemocratic operations, including but not limited to Gladio in Europe using right wing groups to oppose any dangerous left wing governments; and Gladio B, its latest incarnation using Islamic terror groups as its proxies.

Nick Turse has recently written about Obama’s ‘special forces’ operating in 135 countries, where their tasks include sabotage, assassinations and terrorism.

All in a good cause General Molan would have us believe. Making the world safe for democracy don’t you know. He even on ABC this morning) compared the occupation of Afghanistan with that of Germany post 1945! No wonder our foreign policy is a shambles.

Just in case anyone doubts that the spooks hear and adhere to a different drum, recall when Don Dunstan bearded the spooks on why they were still spying on him – the Premier.

I may be paraphrasing, as it is too arcane for google, but my recollection is that the spooks replied that they were sworn & loyal to the Crown not, necessarily to the government of the day.

Anyone who thinks that this allegiance “elsewhere” has diminished might be interested in a bridge I have for sale.

As someone who was on both the NSW Special Branch Files and ASIO Files I suspect I’m in a somewhat better position than most Crikey subscribers to understand the realities of that period and see through the mythologies of Pilger et al.

There were misguided Marxist plots aimed at bringing about the People’s Revolution in Australia. Listening as a youngster to those discussing how, for example, the 1949 Coal Strike would lead inevitably to the desired proletarian uprising there’s no doubt they were deluded, but equally there’s no doubt they believed in their delusions.

Murphy’s raid on the ASIO Office was a farcical, poorly carried out shambles, but that was Murphy. My ASIO File contains humorous reports, including ones in which an ASIO operative kept pointing out unsuccessfully that there was no basis for believing I was a Communist, and the academic job in P.N.G. they were preventing me getting had no security implications anyway.

But Crikey Land has never bothered about details such as this, because they have a line they genuinely believe is a sacred trust.