Six months into his job as federal parliamentary leader of the Greens, Richard Di Natale appeared to up the ante on his party’s ambitions last week when he told a journalist he would “relish” an opportunity to lead it into a coalition government with Labor.

Di Natale went so far as to nominate health as his own preferred portfolio, and suggested his party’s Senator for Queensland, Larissa Waters, might care to join him at the cabinet table as environment minister.

While Di Natale’s bullishness proved good for a few headlines, it was by no means the first time a Greens leader had offered an expansive view on the party’s prospects for executive office.

In 2008, Bob Brown gently admonished his colleagues in the Australian Capital Territory Parliament for knocking back the Liberals’ offer of ministerial posts, instead favouring the safer option of allowing Labor to remain in power as a minority government. Brown’s motivations may well have included a desire to signal to Labor that Greens support could not be taken for granted in future hung parliament negotiations in other, more important jurisdictions.

As it stands, Di Natale’s hopes for cabinet glory could well founder if Labor refused to play ball, secure in the likelihood that the Greens would ultimately baulk from the alternative of allowing the Coalition into government.

A pointer to this was provided after the indecisive result of the 2010 federal election, when Brown resiled from pressing Labor on cabinet posts out of fear that the still-wavering independents might be driven into the arms of Tony Abbott — a clearly unthinkable outcome.

The Greens’ other opportunities to play kingmaker have mainly come from Tasmania, thanks to the state’s accommodating electoral system and the party’s deep historical roots there.

This experience has been progressively transferred into the federal Parliament by Bob Brown, Christine Milne and now Nick McKim, each of whom led the party at state level before moving on to the Senate. All three led the Tasmanian party in balance-of-power situations at some point, but only McKim was able to secure positions in cabinet.

This resulted from Labor’s determination that its own meagre retinue of 13 MPs after the 2010 election did not allow for a cabinet with a sufficient depth of talent and breadth of electoral support, rather than any particular adroitness on McKim’s part in post-election horse trading.

Labor might also have calculated that the responsibilities of government might serve to tame the Greens, rendering them more manageable than they had been under Bob Brown’s leadership during Labor’s period of minority government from 1989 to 1992.

So difficult was this experience that when the Greens again held the balance of power after the 1996 election, Labor actually stood by its usual pre-election talk that it would only govern if able to do so with a majority.

Regardless of whether the Greens have been within the cabinet tent or without, the evidence suggests that the experience of Greens-backed Labor government is usually doomed to end unhappily for both parties.

Whether they like to admit it or not, successful minor parties like the Greens owe much of their appeal to being above the compromises and policy failures that are an inevitable part of governing. Whenever this cover has been removed, the Greens have suffered a sharp drop in electoral support as those seeking to make a generalised protest against the major party establishment have taken their business elsewhere.

For its part, Labor has floundered when its political adversaries and media critics have had the opportunity to paint it as beholden to the Greens.

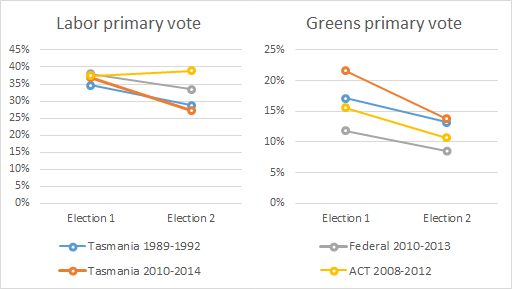

Both points come through clearly in the charts below, which show what happened to Labor and Greens vote shares from one election to the next when the former found itself governing by the grace of the latter.

On three of the four observed occasions, including the period of the Gillard-Rudd government from 2010 to 2013, the Greens vote sagged by between 3.2% to 4.9%.

Labor’s vote was down by around 5% after the aforementioned period of minority government in Tasmania from 1989 to 1992, and by a similar amount at the federal election in 2013. Only in the unusual context of the Australian Capital Territory has its vote held firm.

However, the standout case is the Tasmanian election that followed nearly four years of Labor-Greens government in March 2014, when the Labor vote fell by 9.6% to 27.3%, the Greens vote fell by 7.8% to 13.8%, and the Liberals swept to a clear majority in their own right — a very difficult feat under the Hare-Clark electoral system.

Despite all that, the Greens may well conclude that any chances to advance their agenda through ministerial office, for however limited a period, are in all circumstances too valuable to pass up.

But as the party contemplates a future in which its expanding share of youth support remains faithful to it as it progresses into early middle age, it must remain mindful that the challenges ahead are at least as great as the opportunities.

And I think we only need to wait for the verdict of the ACT on the current Greens Minister to negate most of the speculation above, as I think the political culture in Australia is changing. The more multi-party governments we see, the more we will come to accept them, and the more reluctant Labor will become to poison the Green chalice in the eyes of the electorate. Depending on multi-party agreements to govern is a structural pressure which will lead to more consensus politics, particularly from Labor.

Di Natale’s comments seem to be directed also at Greens supporters, as he tries to move people away from that hard-line mentality of bitter resistance at all costs against the corrupt machine. That kind of abrasive attitude doesn’t help anyone, and could be a real burden for the party as the Green vote expands.

I think his statements are not about raising the Greens profile or scooping up votes in the here and now, it’s about fortifying the base and beginning to prepare the public consciousness for the reality of perpetual multi-party government.

I don’t spend much time any more, William, wondering when/if you’ll ever run the available material on Bob Brown’s Propensity to make whatever pragmatic decisions assist his career.

If ever it does happen it will be an exciting but staggeringly unexpected event.

And this nonsense is why politicial reporters and poll spinners should listen more carefully.

It was an hypothetical, not a wish. Di Natale said clearly he wants the Greens to be the government.

Bill, do you have a large Greens dartboard?

We get it that you don’t understand their basic principle but have you ever written a fair and/or balanced piece about your bete vert?

Now that he has dudded old age pensioners, Di Natalie should think again.