When Gino and Mark Stocco evaded Victorian and News South Wales police, hopping from one hiding place to another in the vicinity of the two states’ border, it was only a matter of time before comparisons were drawn between them and bushranger Ned Kelly.

The similarities between the two manhunts are rather striking.

The Stoccos brazenly outwitted a seemingly ill-equipped police squad, seeking shelter in the same stretch of bushland the Kelly gang called home.

It’s also alleged the men opened fire on law enforcement a fortnight ago, recalling the now legendary scenes at the Glenrowan Hotel where Ned was finally apprehended and his brother, Dan, was killed.

And when photographs emerged of the Stocco pair sporting beards that would embarrass even the most devoted hipster, comparisons with the 19th-century outlaws were cemented.

The Kellys’ last stand was also good business for the papers in June 1880.

“Arrangements have been made to issue a second edition of The Age this morning, if required, in order to meet the demands of our readers,” wrote the Melbourne paper on June 29 that year. Bulletins about their final stand reportedly drew great crowds throughout the day, while in Beechworth, a locale close to where many of the men’s crimes took place, the Ovens and Murray Advertiser noted that almost all business in the area shut down while the police closed in on the Kellys. “Persons [assembled] in crowds in the vicinity of the telegraph offices eagerly awaiting for the latest tidings, which when received was excitedly discussed,” the Advertiser wrote.

Contemporary editors were also hoping the Stoccos’ capture on Wednesday afternoon would also prove to be a commercial boon, with several papers running images of the men’s swollen, bruised faces on their front pages the next morning.

But how does the content of these reports compare to coverage of Kelly’s capture in the 1800s?

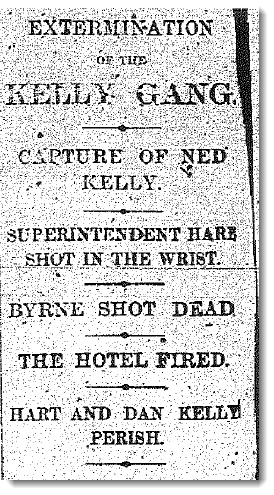

While Ned has been mythologised since his execution, it certainly wasn’t the doing of 19th-century Australian media. They were damning in their assessment of Kelly and his men. The Age and The Weekly Times both referred to the “extermination” of the group, like they were vermin, with The Age adding that the only reasonable feeling about their demise would be gratification.

The Argus agreed, writing on June 29 that year, “Sympathy would have been maudlin … They leave behind them a melancholy array of widows and orphans; the bodies of some of their hapless victims still lie uncovered, appealing to Heaven as did the body of Abel.”

On July 3, The Weekly Times described the men as “beleaguered brigands”, “desperadoes” and even “bloodstained ruffians”.

We can expect more careful reportage today. Crikey notes a portion of yesterday’s Herald Sun is not online for legal reasons. Meanwhile, the most colourful noun bestowed upon the men is “outlaws”, and the closest the media has come to admiration is in the form of praise for their formidable father-son bond.

“At 35, obviously not tied down, Mark’s love of spending time with his dad really is something to behold,” said a somewhat sarcastic but still impressed Greig Johnston in The New Daily. “So, well done Stoccos,” he adds. “Now it’s time to serve your penance (if it’s deemed you need to) and share with us your gifts on building more meaningful father-son relationships. We need you.”

The Kelly-era newspapers also identified ways the manhunt could be instructive for the future.

“The lesson of the Kelly scare is that we should maintain a picked body of men so trained and equipped as to be able to run desperadoes of this class quickly to the earth, even among trackless ranges or waste regions of marsh and scrub,” said The Age.

That paper then continues to chastise the colonial-era police:

“Our police force were reflected upon, not unnaturally, for their incapacity to cope with the difficulty; even their courage was impeached, and their organisation was certainly discovered to be dangerously defective. It seemed as if the arm of the law had been paralysed by the audacity of ruffians whose exploits threatened to reduce our citizens to the necessity of establishing vigilance committees for the punishment of offenders with whom officialdom was incompetent to wage war. Now that the gang have been at last rooted out we cannot feel but renewed surprise that the feat has not been accomplished before. Opportunities must have frequently presented themselves, and have been allowed to pass by from one cause or another.”

Modern-day pundits have also jumped on board that bandwagon. The police copped criticism on social media and in the comments left below online articles, some of which were re-printed in yesterday’s Herald Sun.

“Bit disappointing that ‘the full resources of the police’ were not deployed before they allegedly shot at police,” writes Simon. “They were alleged violent criminals who had been on the run for eight years, but crimes against the public didn’t warrant full resources?”

Reader Greg accuses Victoria’s “keystone cops” of letting the men “do a magical mystery tour up and down the state”.

And another contributor, Guido, simply said, “They probably surrendered out of pity for the police.”

The concern about the expense of such extensive operations also attracted attention in both 1880 and 2015.

The Kelly gang each had a 10,000-pound price tag on their heads, and while The Age did not begrudge its payment to the captors, it certainly pondered whether the money could’ve been spent on better police administration that would’ve extinguished the Kellys’ pluck sooner.

The Daily Advertiser raised the matter of cost with NSW Police assistant commissioner Rick Nugent, who said it was something that would have to be addressed at the end of the Stocco operation. The Herald Sun reader “Biff” was less diplomatic in his assessment: “Great work, probably only cost $2million,” he said.

But perhaps the biggest similarity of all between the media’s coverage of these two groups is its sheer awe at how they manage to evade authorities for so long. The Age got it right on June 29, 1880: “The extraordinary occurrence in a civilised and settled country, of a battle between police and a gang of desperadoes, seems to stagger the community.”

It was the father/son aspect that once would not have been remarked upon.

I’d agree with your comment that The Age got it right on June 29, 1880 when it said, “The extraordinary occurrence in a civilised and settled country, of a battle between police and a gang of desperadoes, seems to stagger the community.”

Sadly in Australia nowadays events similar to that are so commonplace they’re rarely reported fully or adequately.