On Sunday, more than 10,000 Sydneysiders marched to protest against liquor licensing laws. That’s a pretty big turnout for a protest. Led by the “Keep Sydney Open” campaign, the protest was one of the largest in Sydney in recent years. On some counts it was the biggest in Australia’s largest city since 2014’s March in March.

But the reaction to the march from many was dismissive. The Last Drinks coalition held a media conference on Sunday to declare that the lockout’s benefits had been “immeasurable”.

“These laws have saved lives,” the Last Drinks campaign’s Tony Sara told Fairfax Media. “This isn’t about stopping people from having a good time; this is about making sure that people get home safely at the end of the night.”

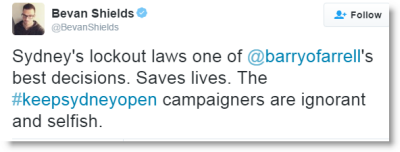

Other commentators went further. Fairfax political editor Bevan Shields took to Twitter to praise the lockout, calling the Keep Sydney Open protesters “ignorant and selfish”.

Some pro-lockout campaigners have been even blunter. Last week, before the rally, anti-alcohol campaigner Rob McEwen wrote in an opinion piece for The Sydney Morning Herald that the “silent majority” were supportive of the lockout, and that “most of us don’t give a stuff if another strip club in the Cross closes!”

The lockout debate has polarised attitudes to a surprising degree. In some respects, it’s a clash of cultures, perhaps even a clash of worldviews. This makes it a fascinating case study of the difficulties of making public policy.

On the side of tougher alcohol restrictions are the people forced to deal with the effects of alcohol-fuelled violence: police, doctors, paramedics and public health professionals. They have a high standing in the community. They also have the evidence on their side.

There’s no doubt that winding back opening hours has a measurable impact on violence. The data is very clear, and has been demonstrated in a number of jurisdictions around Australia, including Newcastle and now in inner Sydney. Where closing times have been moved earlier and where lockouts have been implemented, there has been a fall in alcohol-related assaults, and in associated ambulance call-outs and hospitalisations.

The Keep Sydney Open campaigners understand this, but the debate has not been helped by high-profile contributions like that of entrepreneur Matt Barrie, whose passionate but partly inaccurate post on LinkedIn has been viewed nearly a million times.

Many of Barrie’s claims don’t stack up, particularly his claim that “the statistics have been rigged so that the police are policing to reduce sin, not safety”. In fact, despite a minor error in the statistics used by Premier Mike Baird in his pro-lockout Facebook post of February 9, the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) data does back up the government’s claims: assaults have indeed fallen in the lockout area.

But one of the reasons Barrie’s post caught fire is that he identifies a genuine complaint for many Sydneysiders: that entirely innocent consumers, workers and businesspeople are being punished for the actions of a violent few.

In response, pro-lockout advocates have basically told nightlife campaigners that they’ve got nothing to whinge about. Public health advocates may be right that lockouts reduce violence, but that position has often shaded into outright contempt for the very idea that people would like to spend their time enjoying themselves, at a licensed establishment, late at night.

As Mike Baird wrote in his Facebook post:

“The main complaints seem to be that you can’t drink till dawn any more and you can’t impulse-buy a bottle of white after 10pm.”

“Now, some have suggested these laws are really about moralising. They are right. These laws are about the moral obligation we have to protect innocent people from drunken violence.”

It’s this heavy scent of wowserism, and its implied superior virtue, that strikes many in Sydney’s music and hospitality scenes as hypocritical. Baird might be squeaky clean, but our political class as a whole has a serious problem with alcohol.

Going back decades, there have been politicians with significant alcohol problems who have occupied high office across the land. Jamie Briggs lost his ministership over the summer after sexually harassing a diplomatic staffer. Alcohol was involved. The New South Wales Parliament has itself been the venue for alcohol-fuelled binges, as well as sexual assaults. In 2008, Labor’s then-police minister Matt Brown resigned after stripping down to his underpants and sexually harassing fellow MP Noreen Hay during a late-night office party in his parliamentary suite. In 2003, Democrats senator Andrew Bartlett drunkenly assaulted Liberal senator Jeannie Ferris, and in 2009 Tony Abbott notoriously slept through the vital stimulus package vote after “a couple of bottles of wine” at the parliamentary Members’ Dining Room.

The Keep Sydney Open protesters were of course complaining about more than just hypocrisy. They were pointing out that the industries they represent are major employers and have been seriously affected by the licensing crackdown. Food, drink and the live arts are major components of any global city, and indeed successive governments at state and local levels have been only too happy to champion the “night-time economy”, boost the tourism and hospitality sector, and set up taskforces to spruik the “creative industries“.

A significant number of Australians, particularly younger Australians, work in these industries. PwC figures from 2009 figures suggest perhaps 190,000 Australians work in the pubs and hotels sector. There is a small army of freelance creatives who earn real livelihoods as DJs, performers, music promoters, graphic designers, sound and lighting producers, sommeliers, baristas, and all the other night-time trades that have sprung up or regenerated over the past 20 years. Many combine casual employment with study. Many care deeply about the scenes in which they work.

For these people, night-time activity of the type that the New South Wales government has directly restricted is not just a way to pay the rent, but a legitimate career and even an artistic calling. These activities may well rely on alcohol sales for an important source of their industry’s revenue. But this doesn’t make their commitment to that industry any less heartfelt or genuine.

There’s no doubt that many in the night-time industries would prefer to gloss over — or even deny — the increased violence and harm that accompanies their activities. As I argued back in 2012, many in the arts remain in denial about the alcohol-saturated nature of many of their artforms and workplaces, and the damage done to young lives.

But there’s plenty of denial from the pro-lockout crowd too — for instance, about the negative impact of the lockout on Sydney’s cultural industries. Statistics released last week by the National Live Music Office shows that live performance revenue is down by 40% since the lockout was introduced. The Live Music Office is calling for exemptions to the lockout for live music venues, galleries and theatres.

Late-night workers in the cultural industries are hardly alone in the pursuit of a harmful occupation. Construction workers, miners, truck drivers and farmers also do dangerous jobs that result in horrific injuries or death. Transport and storage, for instance, is by far Australia’s most dangerous occupation, with 65 killed on the roads and in warehouses in 2014. Public debate about this industry has been relatively muted, and there is little impetus to impose new regulations aimed at safety in trucking. Debates about public health in those industries have not been loaded with overt disdain for the very occupations themselves.

Drill down far enough into the lockout debate, and some disconcerting questions arise. Why are the casinos exempted? No sound reason has ever been advanced. And what about other recreational drugs?

A public health approach to the consumption of recreational drugs would also have to admit that our drug policies are wildly inconsistent, and that prohibition as the default position for all non-alcoholic drugs is a century-long failure. A live music industry based around the legal consumption of safe, government-licensed ecstasy would almost certainly be safer and less violent than the current alcohol-based structure. Of course, we only need to put write the sentence to realise the political impossibility of such a regime.

It is possible to imagine a different type of nightlife, one that supports cultural activity and that is not marred by violence or fear.

On Saturday night, Melbourne held its fourth White Night festival, throwing open the city’s streets to all-night arts, music and, yes, eating and drinking. According to Victoria Police, crowd numbers were estimated at an astonishing 580,000. Many were out until dawn. There were no reported assaults or injuries.

Protesters never did need a rational reason for disrupting and endangering the lives and safety of others; but it is of course worse now than in the past.

This assessment is spot on. There must be a way to reduce harm while still allowing a vibrant nightlife to function for the vast majority who have no part in drunken assaults.

Encouraging activities that go beyond simply getting drunk – live music in particular – while discouraging venues with a poor record of alcohol service and violence is the nuanced way to go. Ease restrictions on the former, ratchet up fees and fines on the latter.

I might be a bit thick but does the so called “lock out” laws mean that people already in the pubs/clubs can stay there and drink to their hearts content. It just stops others from entering the said premises say after 1:30 am. So if you organised yourself you could plan to be inside said venue before the cut off time and be locked in..is that correct and if so dont you think its all a bit of a beat up..just go out a tiny bit earlier and alls sweet..happy to be told ive got it all wrong.

Remember, Anthony Hall, that although it’s not a total panacea it does help improve safety on the streets, and dealing with the trash which causes much of the problem becomes more manageable.

What time does the ‘safe’ injecting room at the Cross close?