At the last election, according to Treasury and the Department of Finance, the financial year that begins on Friday was going to see a budget surplus. Not a big one, just $4 billion — but a surplus nonetheless, the first since 2007-08. But by the time Joe Hockey presented the first Coalition budget in 2014, that surplus forecast had changed to a deficit forecast, of more than $10 billion. The following year the forecast deficit had more than doubled to $25.8 billion. This year, when Scott Morrison presented his first budget, the deficit for 2016-17 had surged to $37.1 billion.

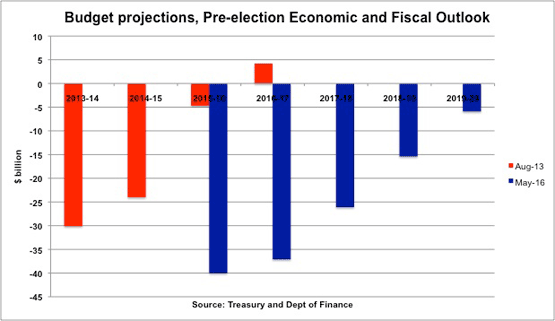

The main offender was that old culprit tax receipts, which we were assured by the Coalition would no longer come in short of forecasts because they had “surpluses in their DNA”. Tax receipts were forecast to be $411 billion back in 2014 but are now forecast to be just $382 billion. Overall, it’s a budget blowout of over $40 billion in one year since the last election. And it’s not the only one — compare the forecasts of the 2013 and 2016 PEFOs, and the problem becomes clear:

If, despite the earnest promise of fiscal rectitude and “surpluses in our DNA”, a government could lose $40 billion in just three years, you’ll see why both Labor and the Coalition’s promise to return to surplus in 2020-21 (a line that received decidedly tepid applause from the audience at yesterday’s Liberal “campaign rally”) should be viewed very sceptically. The Coalition says it will rack up $84.5 billion in deficits before returning to surplus ($3.9 billion) in 2020-21; Labor in its costings release yesterday says it will rack up $101 billion in deficits before returning to surplus ($1 billion) in 2020-21. Of course, the Coalition has yet to show us it’s final election costings; with any luck we’ll see them before Saturday. Friday night, maybe.

But based on what’s happened since 2013, we might still be looking at a $50 billion-plus deficit in 2020-21, instead of a negligible surplus. Sounds implausible? Well, it would’ve sounded implausible if I’d said back in 2013 that the Coalition would be presiding over a $37 billion deficit when they went to the next election.

Labor maintains that its 10-year trajectory is better than the Coalition’s, because its long-term measures like negative gearing and capital gains tax reform will bear more revenue over time. Well, maybe that’s true, particularly given the exorbitant and wholly unjustified cost of the Coalition’s corporate tax handout grows year in and year out. But as each year goes by on that table, the numbers become ever sillier, ever less plausible, ever more likely to suffer the kind of fate the 2013 PEFO suffered of being mugged by reality. Labor estimates a surplus under its policies of $19.851 billion in 2026-27, compared to $6.2 billion in PEFO. But the decimal places create an illusory sense of accuracy wholly unjustified by recent fiscal history, an attempt at budget verisimilitude in what is a fantasy. Much of the media accepts such accuracy without question, just as they accept the budget night numbers without question, when governments of recent years haven’t even been able to get close to their forecasts from 12 months before.

Admittedly, Labor has given voters and the media a week to assess and analyse the numbers, which is far more than the Coalition provided when it was in opposition. But the main story of the numbers is that Labor intends to run a fiscal policy even more stimulatory than the Coalition over the next four years — about 20% more stimulatory, to be exact. Given the performance of the economy since September, there’s no justification for either the Coalition’s level of stimulus or Labor’s. But given falling investment, Brexit, global “headwinds” and the fact that the Reserve Bank will likely cut rates again before too long, maybe more stimulus might be the right short-term call. In three years, we might enter an election reflecting that, even though the return to surplus is further away than ever, Treasurer Morrison and his replacement Treasurer Porter, or Treasurer Bowen, made the right call to keep up the deficit spending to counter the Brexit global recession of 2017.

But after Labor’s numbers, ratings agencies will stick even more strongly to the view that neither side in Australia has the political courage to start bringing the budget back to surplus rather than push it back to the nebulous, eternal fifth year of a four-year budget cycle.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.