The streets of inner Melbourne are suddenly crowded with a whole new breed of bicycle messenger. Two new companies have sprung up delivering food from fancy restaurants to fancy people in the inner suburbs.

There’s Foodora, the global fancy food delivery behemoth, with delivery people in hot pink uniforms. And there is Deliveroo, the smaller competitor taking them on. Their riders wear teal.

It all looked quite fun a few months ago when the early evenings were bright and warm. These days you see the Deliveroo people pedalling along in the freezing rain, their tiny blinking lights barely distinguishable in the mayhem of reflected head and tail lights, and really hoping whoever ordered the meal is going to tip.

The phenomenon has become possible partly because of the increased acceptability of employing people as contractors.

Both companies use contracts, paying people on a piece-work basis and avoiding employment arrangements.

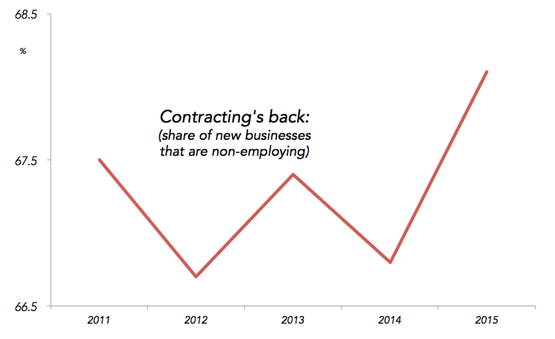

Contracting is huge these days. New business registration numbers show a surge of people registering businesses that have no employees other than the owner. Many of these are likely to be contractors.

Uber, for example, claims it expects to create 20,000 jobs in Australia, without being a major employer. Its drivers show up on an ad hoc basis and shoulder much of the risk themselves. If rules change — for example about the acceptable age of cars — the driver might suddenly be ineligible to work for Uber. And there’s no compensation.

I know a bit about the sector. As a freelance writer I have a non-employing business, and this article is provided to Crikey under an informal contracting arrangement. I am lucky enough to be busy and very happy at the moment. But data suggest not everyone is.

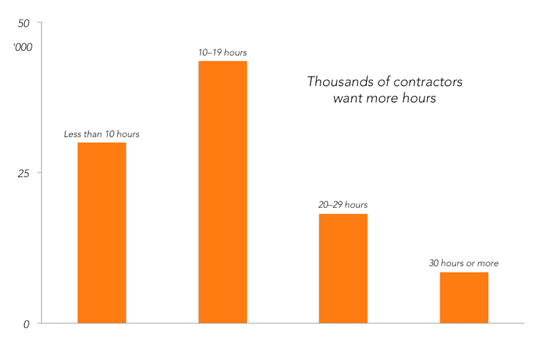

This next graph shows how many contractors want more hours: nearly 50,000 want an extra couple of days’ work each week.

It is clear the underemployment problem in Australia is not limited to part-time employees. The so-called gig economy comes with some nice flexibility advantages for both sides, but the big downside might be in work sufficiency.

And the rise of contracting — in everything from Uber to IT services — has consequences for all of us. It could make the economy more vulnerable to a downturn.

Employment contracts are hard to get out of and so give a certain amount of momentum to an economy. Companies find it hard to lay off staff due to obligations to negotiate and provide redundancy payments. Instead they are likely to try to manage, cutting costs elsewhere and muddling through. That means people are still in work and have money in their pockets, arresting a slide into economic disaster.

The rise of contractual employee relationships means this brake on a sliding economy is now a little less effective than before. This is extra concerning given the fact that monetary policy is, these days, proving somewhat less effective at spurring economic growth. Not to mention that we have a federal government with an apparent philosophical opposition to spending its way out of a slump.

Equally, however, the rise of these relationships could be a tentative step that businesses are able to take during times of putative recovery and a possible sign of brighter days to come. Like the riders pedalling fine food through Melbourne rain, we’re all hoping for a break in the grim weather.

That’s a nice summary of the perils and pitfalls of the so-called “gig economy.

It’s a real dog-eat-dog world for most contractors – badly paid, insecure, terrible hours (yes you get to “choose” just how terrible), no insurance, holidays, weekends or sick days and the constant fear of suddenly having no work at all.

What’s really surprised me about the rise and rise of such arrangements has been the enthusiasm one political party has shown for them.

Not the party of the employers (Libs), but the Greens. In NSW they sent out a press release welcoming the arrival of Uber. Have they just seen the word “sharing” and imagined this descent into Dickensian pre-union working conditions has something to with Nimbin, or the communal Fitzroy house they lived in during the 70s?

Hard to join the world of mortgages and such, even if you are lucky enough to be earning a reasonable amount. Employers are able to take a step back from responsibilities such as accidents, because they don’t have ’employees’ as such. Unions need to get on to it.

Contracts are good for coal mines worrying about black lung. Turn over the contractors every few years and no sufferer can ever prove what happened.

Wait until the iniquitous zero hour contract becomes the norm, as in Britain.

Then the faeces will really interface with the air movement device.