In Japan, they pay a lot less for Australian gas than we do in Australia.

Last month, the spot price in Japan was US$4.27 per gigajoule whereas the average spot price paid in Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide in June was US$6.87/GJ. Australian consumers paid, on average, 60% more for gas produced in Australia than did our customers in Japan.

This is even more bizarre when you consider that, before the gas is shipped, 6365 kilometres to Japan at a cost of US$0.75/GJ, it first has to be liquefied at an LNG plant at a cost of US$1.50/GJ.

We are being skewered; every consumer and every business that uses gas is being gouged. Spiraling energy prices — electricity costs have doubled in recent years too — are all part of the train wreck that is Australia’s energy policy.

Not only is our east coast gas market controlled by a cartel of three producers — Santos, Origin Energy and the Exxon/BHP marketing nexus in the Bass Strait — but gas distribution is also controlled by a fabulously profitable pipeline troika.

Australian Energy Regulator (AER) data shows the return on the equity of one pipeline asset is a dazzling 159%. It’s the sort of return that would have been acceptable to Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico.

As pensioners shiver this winter — “energy poverty” is on the rise — the gas cartel could also send more manufacturing businesses in Australia to the wall, or drive them offshore, as was the case with leading fertiliser group Incitec.

The spot gas market run by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) is illiquid, lacks depth and is tightly controlled by the three dominant players. Although they call it a “market”, it is not really a market. A real market requires transparency and price discovery. This is a cartel and cartel prices recently spiked to $14.40/GJ on July 5.

To lend global perspective, the average spot price on that day, July 5, of US$10.80/GJ, was more than three times the spot price of US$2.69/GJ on the same day in the US, where there is a true market.

Yet it is not merely against the efficient US market where Australian gas prices seem grossly inflated. Our largest export market is Japan. On that same day in Japan the contract price was US$7.23/GJ.

Besides the stranglehold of the producers’ cartel, gas prices have shot up because the transmission system in Australia, that is the pipelines, is extremely expensive.

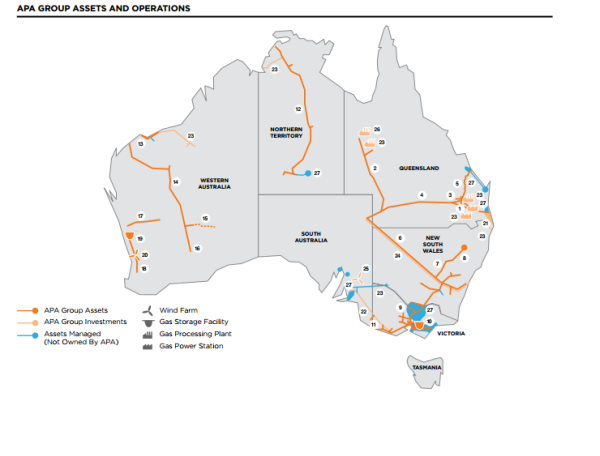

Gas transmission is dominated by the pipeline-owner APA Group.

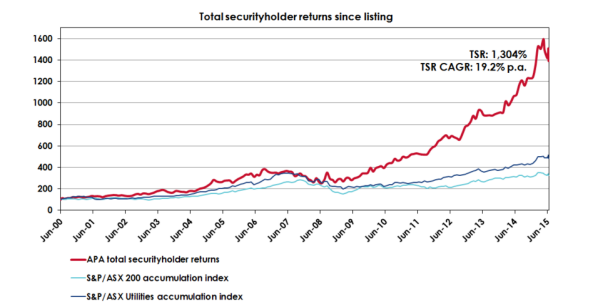

APA is one of the very best performers on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). Since floating in 2000, its shares have delivered its investors a return of 1304%. In share market vernacular, this is a “13-bagger”, increasing in value 13 times its original investment in 15 years. A truly phenomenal run, and a credit to management.

Unfortunately, their shareholders’ gains have been their consumers’ losses.

How does an essentially dull business make such scintillating profits though? It runs unregulated monopolies charging its customers monopoly prices.

The recent Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) Inquiry into the East Coast Gas Market produced a number of examples of price-gouging by the monopoly gas transmission providers. The other two are Jemena and QIC. While the ACCC did not name the offenders, its dominance suggested to most observers, including APA itself, that APA must have been one of them. It denies predatory pricing, instead putting its success down to lifting pipeline capacity, getting more gas through each pipe.

Chief executive Mick McCormack told the audience at an industry dinner in Sydney last week transmission charges made up only 5% to 10% of retail gas prices:

“So the pipeline industry hasn’t been the party putting very steep price increases to the market — we’ve just charged what we’ve always charged and tried to grow the gas market.”

Ominously, he also flagged a research report from investment bank JP Morgan estimating prices would rise a further 40% over the next decade.

Responding to questions for this story, an APA spokesperson said the group was making the same rate of return as it did when it listed, saying the 66% rise in prices was mostly due to the effect of trebling of demand from the three LNG projects at Gladstone in Queensland (offshore demand had sucked away domestic supply).

“What is certain is that the pipeline transmission charges have not contributed to increases in the domestic gas price. APA has not increased pipeline tariffs on its east coast pipelines in real terms for at least a decade, so any increase in delivered gas prices hasn’t come from APA so called ‘gouging’ its customers,” said the statement.

In its inquiry, the ACCC noted many examples of price-gouging in the transmission industry and it found that price rises would not have been nearly so rampant if the monopolies were regulated.

“So too does the internal analysis carried out by one pipeline operator, which indicated that it is earning 70 per cent more revenue than it would if it was subject to full regulation.”

Lest we be accused of selective quotation, the ACCC goes on to detail a selection of pipeline augmentation projects carried out in the last two to three years in the following graph. The Australian Energy Regulator has a benchmark return on equity for 2013-15 on such regulated projects of 7.1% to 8%. For the weary consumer though, these projects were not regulated.

Only one of the projects came in under the AER’s benchmark. The expected returns on these projects being 1.4 to 20 times higher than the benchmark return – with the most extreme example producing a staggering return on equity of 159%.

The lack of regulation of APA’s monopoly assets is detailed by APA itself in its annual report.

The lack of regulation of many of APA’s gas transmission pipes is in stark contrast to the situation in Europe, New Zealand and the bastion of capitalism, the US.

It appears that overseas, even in the US, it is recognised that monopolies need to be regulated.

In the US, all major interstate transmission pipelines are regulated unless the pipeline operator can demonstrate that it lacks significant market power. No pipelines have been able to demonstrate this to date.

The US market also demands high levels of disclosure by pipeline operators. They must report on a quarterly and annual basis:

- the pipelines balance sheet, cash flow statement and profit and loss;

- detailed information on the value of the pipeline’s assets and accumulated depreciation;

- detailed information on the revenue received for transportation, storage and other services and volumes transported; and

- detailed information on the costs incurred in the provision of services, including the cost of any capital works under construction.

In contrast, customers wanting to use a transmission pipeline in Australia must head into negotiations essentially blind to any of these negotiating tools. The market in Australia is completely opaque with all the information withheld by the transmission companies.

Our governments and regulatory bodies allow this price-gouging, even defend it, despite the encroaching scourge of energy poverty and the deleterious effect of high gas prices on the economy overall.

Globally, the price of gas, along with tumbling crude oil prices, has been crashing but in Australia prices have been marching steadily higher. On the spot market on June 30, the price even touched A$29/GJ.

*Bruce Robertson is an analyst with IEEFA.org

*This article was originally published at michaelwest.com.au

Once again; the irrefutable fact Australian governments are enablers of energy ‘carpetbaggers’ whilst forestalling the Australian community commitment to affordable renewable energy development.

According to the Limited News Party, the carbon tax was supposed to drive up the price of energy and that was a bad thing : but this sort of cartel driving up the price of energy is all right?

Yet again our hero government shows us how they are looking after all Australians…

Big Energy are big donors to the Liberal Party. Of course, that has nothing to do with anything….

Note that the rampaging price of gas, and thus electricity, is irrelevant with renewable sources. No fuel costs to gouge, unless the sun and wind decide to cartel up!

Good that the Liberal Party has been so strenuous in slowing renewable energy, and continue to be so to sandbag the interests of fossil fuel producers and generators, and the rabid right and National Party. Forget Turnbull and Hunt’s rhetoric – that is what they are doing. We are paying *more* as a result.

Can’t agree more with Graybul. TheNEM is an artificial “market” erected for no good reason than to serve the neo-liberal ideology that prevails in Canberra and elsewhere. The public service is drilled inner-liberal nonsense. So, when you ring and complain about the no reasonable return on investment in installing solar energy, we are informed that a price of 5c per kilowatt is OK because electricity providers pay from 5c to 11c, except when they are being gouged by the nonsensical price peaks that are increasingly plaguing the market. This charge is imposed on solar users so that they “contribute to the net-work costs.” Apparently no-one is to contribute to solar installation costs these days. The claims are nonsense. If you want domestic solar panel operators to contribute to network costs, then you charge a network connection fee rather than limit the minimum charge for electricity returned to the network to 5c. As it is, the cartel charging for gas and electricity is forcing pensioners to shiver in the cold. Something needs to be done. Protests need to be heard so that star and federal governments respond to price gouging.

If the Federal government is so busy trying to Americanise our medical system, why doesn’t it Americanise our energy delivery system, instead of allowing practices that artificially disadvantage Australian business in the global market.

The obvious response is for one of the PM’s admired innovators to start importing LNG to Australia sourced from one of Australia’s big 3. The ships wouldn’t even need to leave the dock, just load up & discharge on the same day. Indeed a notional or virtual transfer would be sufficient, thus allowing multiple loading & discharges from the same ship on the same day. How’s that for productivity!?

Where can I buy shares?

Brilliant!