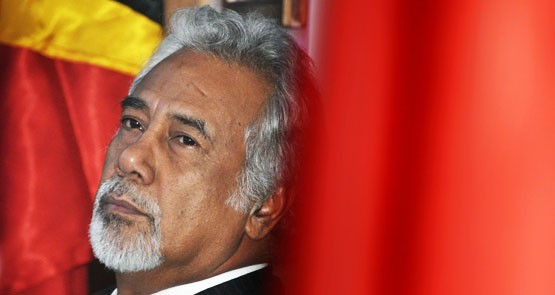

It was no surprise when East Timor’s former resistance leader, president and prime minister Xanana Gusmao announced he would support the Fretilin Party’s candidate for the presidency, Francisco Lu-Olo Guterres. Gusmao had said as much more than a week ago, and the move had been expected since last year.

Gusmao’s party, CNRT, is now also expected to formally endorse Lu-Olo’s candidature in the March presidential elections. This means that the country’s two largest parties, which have recently operated in a “government of national unity”, are likely to have a lock on the presidential race outcome.

What had been referred to as the serial presidential candidate’s “turn” to become president is widely viewed as cementing arrangements for a further term of a “government of national unity” coalition between CNRT and Fretilin following parliamentary elections in the middle of this year. The “government of national unity” was initially hailed as a step towards stability for East Timor, with former rivals CNRT and Fretilin agreeing to form government, along with the Democratic Party, which was removed from the governing group last year.

CNRT and Fretilin previously had a fractious relationship following the country’s descent into chaos in 2006, leading to Australian-led military intervention, and the bitterly contested 2007 elections. Gusmao stepped down as prime minister in 2015 to allow the “young generation” Fretilin member Rui Araujo to become prime minister at the head of a coalition government, which was seen as a healing move between the two parties.

However, observers noted at that time that the coalition left East Timor without a viable opposition. At the time it was thought this move towards “stability” would be productive so long as it did not become permanent, which could create a “dominant party state”.

Dominant Party States, such as Singapore, Malaysia and Cambodia, have elections in which the dominant party (or coalition in Malaysia’s case) is all but guaranteed success. In such cases, elections do not equate to democracy.

East Timor came out of its brutal Indonesian occupation with a strong commitment to democratic principles, and its elections since then have marked the country as the most democratic in south-east Asia. However, the possibility that East Timor would create its own “dominant party” structure has taken a further step closer with Gusmao’s endorsement of Lu-Olo as president, and the subsequent likely return of a ‘government of national unity’.

While outgoing President Taur Matan Ruak has started his own party, the Popular Liberation Party (PLP), to contest the parliamentary elections, it is unlikely to gather enough votes to form an alternative coalition, much less win government in its own right. The PLP will campaign on an anti-corruption ticket.

The creation of the PLP follows public concern about a significant rise in alleged corruption by government members, their families and close associates. What have been dubbed East Timor’s “50 families” control most lucrative government contracts, which have mostly been let without open tender.

These government contracts are paid for from East Timor’s government drawing down on its Petroleum (sovereign wealth) Fund, at around a billion dollars a year beyond sustainable estimates. East Timor’s Petroleum Fund has about $16 billion in it, but this is expected to start declining as revenues from the Timor Sea oil and gas field start to dry up over the next few years.

It has been suggested that oppositional parliamentary politics, which privileges contest over harmony, is not a suitable model for developing countries with no prior experience of competitive politics. There is some evidence to support this claim.

However, closed political processes, including those dominated by a single party of coalition of parties, are also deeply problematic. Such closed systems are all but universally prone to high levels of official corruption and for acting in both an authoritarian manner and to arranging political processes to ensure their continuation in office.

East Timor’s “government of national unity” has put forward new legislation on the country’s otherwise independent National Election Commission (CNE), ahead of the elections. A key electoral official involved in establishing East Timor’s electoral system has noted that the legislation effectively compromises the independence of the CNE.

Despite having elections for both the presidency and the parliament this year, it may be that East Timor’s experiment with open democracy is, at best, being compromised.

*Damien Kingsbury is a Deakin University professor of international politics, co-ordinator of the Australian ballot observer missions to East Timor in 1999, 2007 and 2012, and proposed for 2017. He has written and edited a number of books on East Timor’s politics.

Couldn’t the same question be directed at Australia? Federal certainly but even more particularly the states.