Is inequality in Australia getting worse? Is the Gini coefficient going up or down? Who’s right, Bill Shorten or Scott Morrison and the conservative newspapers beating the bushes for academics who’ll back them up?

It doesn’t matter, and the longer the government and its media allies debate it, the more they’ll play into Shorten’s hands on what will become a key issue for the next election.

Inequality is a central outcome of the kind of market-based economic reforms we’ve pursued since the 1980s. That’s how neoliberalism works. It has made us all wealthier — even the poorest Australians are wealthier than they were 30 years ago, in real terms. But the wealthiest have benefited more than the rest of us. This is indisputable. A Productivity Commission paper in 2013 explained it:

“Between 1988-89 and 2009-10, the incomes of individuals and households in Australia have risen substantially in real terms and in comparison to trends in other OECD countries, with particularly strong growth between 2003-04 and 2009-10. The increase has mainly been driven by growth in labour force earnings, arising from employment growth, more hours worked (by part-time workers) and increased hourly wages. While real individual and household incomes have both risen across their distributions, increases have been uneven. The rate of growth has been higher at the ‘top end’ of the distributions than the ‘bottom end’.”

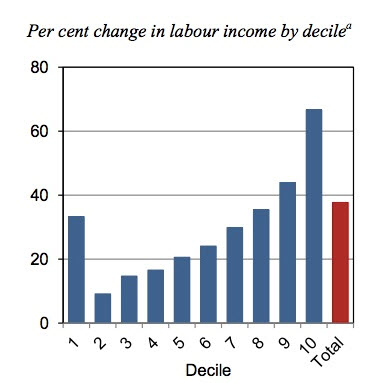

One graph from the paper sums it up well:

It also makes intuitive sense — unusually, for economics. Everyone has done well from a more open economy coupled with Australia’s very effective welfare system, but it has allowed high-income earners both to make more money in a more globalised economy, and to keep more of their income because we’ve reduced the redistributive nature of our tax system.

[The surprisingly quick death of neoliberalism in Australia is underway]

Arguing the toss about this doesn’t help neoliberal advocates, because two things have happened in recent years that have changed the political debate.

One is we’ve realised that increasing inequality comes with a price. We might in the past have grumbled about high corporate remuneration, for example, but it was mainly envy talking. Now we’ve worked out greater inequality is economically harmful. Who says? Such raving lefty institutions as the International Monetary Fund and the OECD. A 2016 IMF paper concluded that while “there is much to cheer in the neoliberal agenda”, “the costs in terms of increased inequality are prominent … Increased inequality in turn hurts the level and sustainability of growth. Even if growth is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal agenda, advocates of that agenda still need to pay attention to the distributional effects.”

A 2014 OECD paper found that “income inequality has a negative and statistically significant impact on medium-term growth. Rising inequality by 3 Gini points, that is the average increase recorded in the OECD over the past two decades, would drag down economic growth by 0.35 percentage point per year for 25 years: a cumulated loss in GDP at the end of the period of 8.5 per cent.” How? The OECD argues via education. “The evidence is strongly in favour of one particular theory for how inequality affects growth: by hindering human capital accumulation income inequality undermines education opportunities for disadvantaged individuals, lowering social mobility and hampering skills development.”

Inequality isn’t a harmless, if annoying, by-product of neoliberalism, but actively harmful to economic growth.

[Even Keating now admits that neoliberalism should be dragged out the back and shot]

What’s also happened is that the electorate has started to react to not merely inequality in outcomes, which debates over Gini coefficients etc deal with, but the perception the entire system is unequal. At one end are corporations, which pay little tax, gouge consumers, cut wages and get “consulted” on any changes that might affect them, and high-income earners who, as Bill Shorten cannily argues, get first-class treatment in the tax system, and then there’s everyone else, who have to endure stagnant wages, soaring prices from privatised and corporatised utilities, and who have little choice about how much tax they pay.

Arcane debates about Gini coefficients — 98% of voters wouldn’t have a clue that that is — are no match for the lived experience of households who think the economic system is delivering for elites but not for them. Shorten is working on that level. Morrison and the government’s cheerleaders in the media are operating at the level of a common room argument in an economics faculty. Some, like Tony Abbott and One Nation, are operating at an even more visceral level, telling voters it’s all the fault of various designated, recently arrived Others.

And that’s just in Australia where, thanks to Medicare, a good welfare system and public education, overall inequality has only risen a little. In other countries, where wages have been stagnant for longer and inequality has grown a lot more, the issue is far more live. In the United States, Donald Trump rode exactly these sort of concerns into the White House, only to preside over attempts to implement an even greater pro-inequality agenda than previously.

Scott Morrison better hope that eagerly predicted wages surge arrives sooner rather than later.

There are two types of inequality that matter, one measured by wealth, and one by inter-generational change in wealth. In a genuinely merit based society, the sort of society I believe in, we could tolerate a great deal of inequality of income or wealth provided that we were confident the differences in income and wealth were a consequence of individual talent and effort, and not who your parents were or whose back you rubbed. Lots of people say they believe in equality of opportunity and merit based advancement, but only an exceptional few really do. Australia does not fare as well in the inter-generational equity stakes as Andrew Leigh thought we did – based on Mendolia and Siminski’s work we are in the bottom third for inter-generational mobility, whereas Andrew had us about middle of the pack. Inequality matters, but what matters more is when your lived experience is that you cannot get ahead when you work hard and long and well, and people you know are freeloaders and wealthy by inheritance rather than work wiz by you in their new leased sports car to a mortgage free home in the eastern suburbs.

Your last sentence reminds me of correspondence I had with an American who had the misfortune of sharing a room with Dubya in his first year at Yale. He couldn’t believe how dumb GWB was, or how lacking in interest he was in academic pursuits. Said guy was furious because he got there on merit, not family background.

The great nonsense of the neoliberal era: “Everyone has done well from a more open economy”. Sorry, neoliberalism has *never* matched post-war social democracy.

1950s-60s averages: GDP growth 5%+, inflation 3.3%, unemployment 1.3%. Stephen Bell documented it 20 years ago, but facts never get in the way of the mantra. The major problems of the 1970s were oil embargoes and US printing money – transient problems that would have been managed.

If you also counted reduced services, increased corruption of democracy, house prices and job insecurity you’d get closer to why people are pissed off about inequality.

Well said, everyone.

One of the problems with economics is its utterly self-referential nature. For more rigorous reasons of why inequality hurts economic growth one must venture into psychology, where much research shows that co-operation and productivity are sorely affected by a sense of unfairness. It doesn’t even have to be real, but in this case it is.

Gini co-efficients are academic exercises, not scientific ones, and should only be looked at as a curiosity. Wealth in Australia is overwhelmingly an issue of being born in the right family, not one of merit. Hard work gets you callouses, more likely than riches.

Then there is the welfare issues, where the most vulnerable – unemployed and the unwell/disadvantaged, are being hounded off and paid little, and having to pee in a jar for the privilege.

As a group, we are not quick to pick up how utterly we are being screwed, by the wealthy, for the wealthy. The light is coming on, but ever so slowly.

Increased crime is also a result of increasing inequality. It’s not poverty that is a necessary determinant of high crime, it’s relative poverty. Several studies in the united states have demonstrated a significant correlation between the two.

Well said Bernard. Neoliberalism should indeed be take out the back and shot, as Paul Keating has, perhaps belatedly, realised. The problems you identify are real but the growth in inequality brought about by neoliberalism is not entirely due to the important factor noted by the IMF. It is also brought about by the fantasy belief, integral to Neoliberalism, that “it is as if” the economy works like the economy modelled in neo-classical economic theory.

A sad belief that everything that can possibly be turned over to private capitalists should be turned over to them and governments should maintain only a minimal state with low taxes s also part of neoliberalism and is responsible for the dreadful cost of toll roads, especially in NSW. It is responsible for the weird belief that free trade in gas will be wonderful because it is free trade. It overlooks the reality that gas is a scarce resource and that it is absurd to allow unbridled developed of LNG exports, which draw heavily on electricity for refrigeration of natural gas and thereby not only increase demand for power but soak up a key resource like natural gas, whose price can be used under the NEM rule as the base on which wholesale electricity prices are built. Markets do not work in the real world “as if” they were perfectly competitive complete markets of neo-classical economic theory. Neo-liberalism is thus responsible also for the surge in electricity prices, driven by the fantasy rules of the faux NEM.

Real incomes measured by averages of cost over the country fail to recognise the significant local costs that workers and traders suffer from road tolls and rising electricity prices.

As Bernard says, enough of the electorate will no longer believe that a government’s only concern is with “growing the pie” rather than with how the “pie” is divided. It will no longer believe that economic growth, like a rising tide, will lift all boats. It will to demand that the NBN be second rate and that a significantly commercial rate be charged so that it can later be privatised, with all the benefits that the privatisation of Telstra has brought poorer Australians.