At a time of bitter division over Australia’s economic direction, when business is being assailed by deep-seated community anger about how it conducts itself, you’d think the government would be eager to showcase the capacity of the business sector and workers’ representatives to work together very effectively for the good of both — and the good of the country.

Employer groups run the industry superannuation sector, along with unions, and it’s a hugely successful model that contributes more than a third of Australia’s vast $2 trillion-plus savings pool and earns strong returns for low fees. It’s a credit to both corporations and unions that they’re able to oversee such a successful sector.

Not, however, in the eyes of the Liberal Party and its handpicked journalists. The Liberals have always been at war with the industry superannuation sector because of the involvement of unions, and always will be. The interesting thing is always the pretext invented by the Liberals to justify criticising the sector.

[The next stoush on superannuation is coming]

Faced with the frustration that the industry super sector continues to massively outperform the retail super sector controlled by the big banks and in fact is widening the performance gap, what to do? Financial Services Minister Kelly O’Dwyer has been peddling a line that industry super funds are somehow channelling money into a vast trade union war chest, as part of a broader government attempt to demonise all unions as corrupt and suggests there’s something faintly criminal about Labor politicians with links to them, like Bill Shorten. It’s a reversioning of Tony Abbott’s dismissal of industry super as run by “venal union officials”; “rivers of gold” is a phrase devised by the government that has recurred across different media outlets — O’Dwyer has used loyal News Corp stenographer Simon Benson to prosecute the “rivers of gold” angle, while Tony Boyd and Jennifer Hewett at the Financial Review have been pressed into service on a related issue, the suggestion that industry super governance is somehow corrupt. O’Dwyer is renewing the government’s efforts to force industry super funds to adopt the same sort of board governance structure as retail super funds and the banks. You’d think that after the AUSTRAC allegations against the Commonwealth Bank that the government wouldn’t think bank-style governance was the kind of model it should be pushing, but O’Dwyer has been trying this since the moment she became a minister and was literally laughed at.

Benson of course is the reigning Drops King but not exactly a policy hot shot (he once argued people should be allowed to use their super for housing instead of being “ripped off by union-run super funds”, despite there being no “union-run” super funds in the country). Yesterday, he offered a peculiar piece on how the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority would “crack down on “dark payments” from industry funds to their associated unions — now estimated at more than $8 million a year” which “would further tighten the noose on what the government has described as ‘rivers of gold’ flowing from super funds and workers’ entitlement funds particularly to the union movement.”

[Is our super pool a dead weight on the economy?]

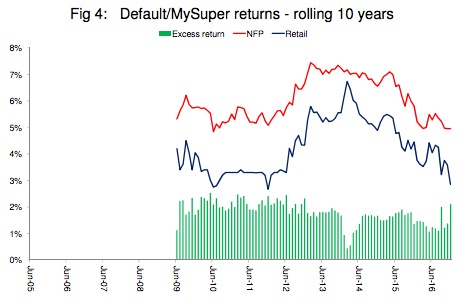

Prompted by this Walkley-standard expose, we wondered what “rivers of gold” might flow from other parts of the superannuation sector — such as from retail super funds to the big four banks and AMP by way of fees. Fortunately, Rainmaker Consulting produced a report in May this year that gave us a sense of how wide and how golden the river is that flows from the retail sector. In 2016, $8.7 billion in fees flowed from retail super customers to the big banks. The report also found that industry and corporate super funds account for 42% of funds under management in the sector, had 45% of super members, and received 42% of all fees, while retail super funds had only 29% of funds under management from 45% of members, but received 50% of all fees. Despite this disproportionate allocation of fees, retail funds continue to underperform the non-profit sector.

For some reason, O’Dwyer and his media cheerleaders want industry super to abandon the highly successful governance model that has driven its out-performance, in favour of a higher-fee, lower-return big bank model.

Luckily, however, fees have fallen even for retail funds in recent years. Rainmaker notes:

“Since 2013 when MySuper and FOFA [Future of Financial Advice reforms] were introduced, while fees for already low-cost NFP funds have stayed at about their average rate, fees for retail default funds have fallen sharply… in 2012 the average member in a workplace retail fund was paying 1.96% (assuming no corporate volume discounts) but that same person if they swapped into the average retail MySuper product would one year later have paid fees only half that level being 1.01% – this is as a direct result of retail workplace funds unbundling previously embedded advice commissions.”

Of course, the Liberals fought tooth-and-claw against FOFA, and were only narrowly defeated in their effort to repeal it at the behest of the big banks, while they tried to use MySuper as a Trojan Horse to create open slather in the default fund market, to help the retail sector. Even so, $8.7 billion in fees is a tidy sum for the big banks.

And that’s the problem for O’Dwyer and her stenographers: no matter what niche issue she picks to try to demonise industry super, retail super is always, always, worse. Maybe the Liberals should just start thinking of industry super not as “union-run” but as “employer-controlled”, and suddenly the sector’s strong performance will be something they can celebrate.

“Always ALWAYS worse” ?

I used to believe firmly that low fees was the end game until I started researching changing my super fund, annoyed that my employer didn’t have an ethical fund. Long story short, lots of research later, Australian Ethical Super had some of the highest performance returns … it’s hard to compare over time as the market has strong and weak periods, but here’s the summary — https://www.australianethical.com.au/super/performance-and-returns/

Bottom line is I’m aiming for 10%-15% annual compound growth, but averaged over a decade as the market fluctuates. What leaves me annoyed though is that I need to get up at $200,000 or $250,000 to consider SMSFs Self Managed Super Funds where the there are several funds I can get in the range 15%-20% and a handful at 20%-25%.

Chris, I think most of the bigger industry funds offer an ethical fund. I know of a few that do and they are big and cover a huge number of workers. Perhaps just looking around would have done the trick.

“Financial Services Minister Kelly O’Dwyer has been peddling a line that industry super funds are somehow channelling money into a vast trade union war chest,”

So, Ms Kelly, have them charged. There are pretty strict rules around what superannuation bodies can invest in, and channelling money into unions isn’t one of them, and would I am almost certain be an offence. Set the AFP on them if you have evidence.

How much is retail super pouring into this, their Limited News Party Puppet Show Revue, to get the keys to this nest egg hen-house?

Meanwhile they have this ‘Nudge Nudge Wink Wink Punch and Judy Show’ with the banks a couple of times a year – to avoid a royal commission.

Talk about proctologists – going through the motions.

Hands off our (industry) super…you stupid woman!

There should be a law against politicians making ‘fake news’ statements, and misleading the public. Where is O’Dwyer’s evidence that the union movement rips off the super earnings of its members?

Labor party…PLEASE ask her this question in parliament, since it appears all media (Crikey excepted) are too damn lazy/idealogically challenged to do so!

Some unkind people are opening that Kelly O’Dwyer is probably being paid by the banks / retail funds to push the line that she does. The question: is she on the take?

Opening = opining

Damned figures, making government ministers/spokesbots out to be mendacious morons.

They ortabe banned.