Australia’s Reserve Bank is feted around the world. It’s a global leader and innovator. But there’s one thing it does in an old-fashioned — possibly even dangerous — way: it moves official interest rates in multiples of 0.25% and only in multiples of 0.25%.

Right now, with the Australian economy in an extremely unusual position, it is time to ditch that old practice.

‘The world is continuous but the mind is discrete’

Raising and lowering official rates by 0.25% at a time is a global central banking trend. The US Federal Reserve hiked rates by that amount last week. But the practice lacks a rationale.

Rate hikes have changed in size before. Up until 1716, the UK changed official interest rates by a percentage point or more at a time. Then, in August 1716, it innovated radically, tweaking rates down from 4.5% to 4.0% .

British interest rates moved in multiples of 0.5 for a quiet couple of centuries until 1974, when the Bank of England first cut rates by 0.25 percentage points (or as the pinstriped traders in the city like to call it, 25 basis points).

As measurement of the economy has become more precise and understanding of monetary policy has improved, finer adjustments of policy rates have come to seem important. So why not move official rates a few basis points at a time? Commercial banks have no qualms about moving rates by less than 25 basis points. They fiddle with their interest rates down to the second decimal place.

Take a hike, Australia

Most market watchers expect Australia’s interest rates to rise in 2018. Because interest rates are at a record low of 1.5%, a hike of 0.25% will be — in proportional terms — the largest in Australian history. That proportional impact matters because households will feel it in their interest payments.

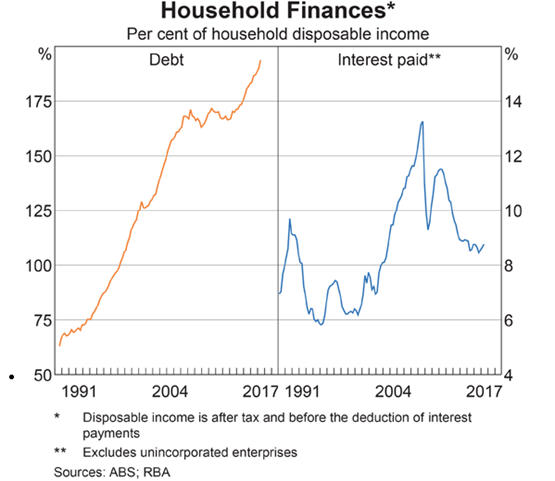

At the moment, low rates permit Australia to maintain an extremely high household debt with a relatively benign interest rate burden, as the next graph shows. A big interest rate hike could change that peaceful coexistence.

Higher interest rates are supposed to act as a brake on borrowing, and to cool the economy.

The next rate hike is fiercely anticipated, with voices already being raised in a cacophony of anger. On one side are those who think rates have been low too long and want to clunk a lid on Australia’s massive household debt. On the other side are those who watch our pathetic wages growth and inflation with a deep fear in their hearts of what might happen if higher rates cool the economy further.

According to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), both concerns are probably justified. In a report released in December, it spent a lot of time on Australia’s unusually high levels of household debt. What really caught their eye was how Australia’s debt levels are both unusually high and still rising.

“In Australia … heightened competition among lenders seems to have resulted in a relaxation of lending standards,” said the BIS.

But — mindful of Australia’s unusually high share of variable rate mortgages – the BIS did not suggest a headlong rush to lift interest rates.

“Interest rate hikes cause aggregate expenditure to contract more than cuts would cause it to expand,” the report argued.“Credit-constrained borrowers cut consumption a lot in response to interest rate hikes, as their debt service burdens increase.”

The argument implies interest rate hikes should not be the same size as cuts. This makes a kind of intuitive sense – while economic crashes are short and sharp, recoveries tend to be slow and tentative. If the economy’s patterns of growth are asymmetrical, why should interest rate hikes be the same size as interest rate cuts?

We can see the Reserve Bank applying that logic already, in fact. During the global financial crisis they cut rates in big chunks of 1% and 0.75% at a time. But we have never before seen them raise rates by less than 0.25%.

Friction over fraction

At eleven meetings during 2018 the Reserve Bank board will face a tricky binary decision – hike by 0.25%, or don’t hike at all. Beyond the boardroom windows Sydney’s housing market may already be turning cold and lifeless. A hike of 0.25% may be more than they can stomach.

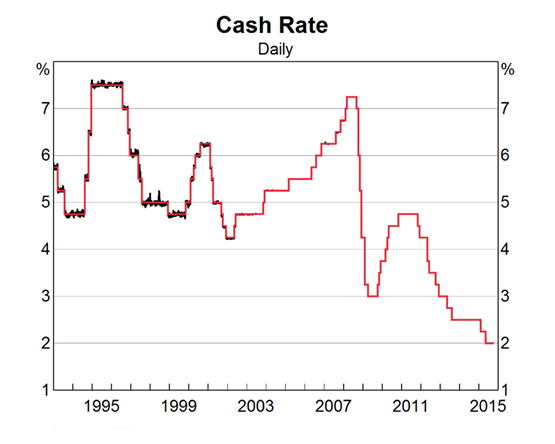

There is no technical reason not to raise rates less than a quarter of a percent. Our central bank is very good at getting the interest rate to sit at the official cash rate via its open market operations. That skill is shown in the next graph which depicts the target (red line) and actual (black line) rates in the overnight cash market. Since 2003 they line up completely.

For the health of our economy, the Reserve Bank should free itself from the way things have always been done and move interest rates by as much or as little as needed.

If there is one certain point to come from this, and a thousand similar articles, it is that economists aren’t worth feeding.

one certain point about this reply is that this guy is no economist.

Is he writing from a building in a desert? Is his head in the sand? Or is he getting an inside view of a camel?

The thrust of the article is that there is room for flexibility in the scale and direction of RBA moves on interest and that any move will be more po.tent at present due to the small base

I think the one certain point to come from this, and a thousand similar comments, is that people who write comments without substance like your comment aren’t worth feeding.

Hmm. I would like to see all of the useless clods and that includes most economists have to work in the world they claim to understand. Out of the office, everyday issues where you might not have next weeks rent. Try that on.