We strolled through fields all wet with rain/ And back along the lane again …

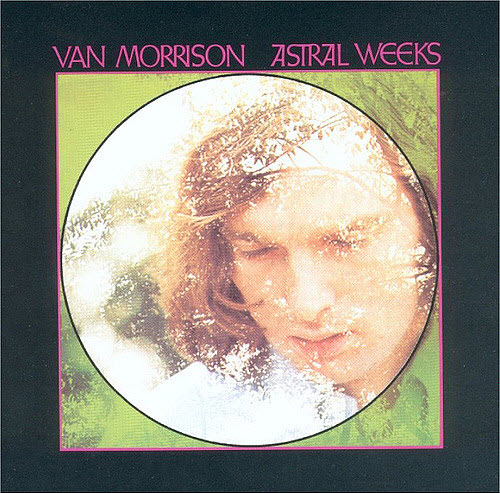

The album starts, the first track explodes from the speakers, and the first line explodes from the first track: “The Way Young Lovers Do.” Nineteen sixty-eight has a lot of anniversaries to it, but one of the most beguiling is the 50th of Astral Weeks, Van Morrison’s second studio album, and absolutely the strangest and most singular album in the rock canon. Driving, rocking, drifting, folk, rock, jazz, what the hell is it? It jumps track by track from acoustic pop, to near-psalm, to rock jazz impro punk, to runaway train. Record of a strange time in its creator’s career, it applies the full force of his life and young memory into 47 minutes.

By the time he came to record Astral Weeks in New York in 1968, Morrison was 23, and had already written pub-pop classic “Here Comes The Night” and then “Brown Eyed Girl”, enough to achieve a minor immortality. Trapped in the US, out of money, in a contractual dispute over recordings, a half-century ago this month, he’d started jamming and putting songs together with folk/cool jazz musos in Boston, flautists and expressive bassists. He’d married for a visa. He was writing furiously, a man driven by his life, a Belfast protestant rejected by protestants — his parents were Jehovah’s Witnesses — who had become passionately attached to the Irish poetic tradition, Patrick Kavanaugh in particular; poetry of hardness and disappointment, and the sun breaking over the mud of the fields. So it glistens, but who could care?

If I ventured in the slipstream/ between the viaducts of your dream …

Astral Weeks is a Belfast boy hitting the ’60s full-force. It is extraordinary writing, sure-footed, as only someone coming out of a tradition can be. With his thick book of songs, Morrison came to Century Sound studios, for three days of sessions, with a hired crew that happened to include some of the best jazz-men in New York at the time. Morrison’s Boston crew were cruelly excluded from the sessions, but it was the making of the thing. The (double-)bassist was Richard Davis, who was the bassist; Connie Kay from the Modern Jazz Quartet was the drummer; Charles Mingus’ standby Jay Berliner was the guitarist. The result is what rock sounds like when real musicians play it, the seemingly effortless confidence of half-a-dozen able to wander away from each other and come back again, and never drop an eighth-beat.

Each of the key songs has one big thing, one strategy they’re trying: a slow layering build in Astral Weeks, guitar and flute – yes, the flute works – working independently within the beat; in “Madame George”, it’s sprawl, the song following Van’s voice and a single violin, wherever it goes, sheer force in “Young Lovers” – near jazz-punk, the sole survivor of the middle session, that didn’t otherwise come together – and, most extraordinarily of all, “Ballerina”, which builds a vast arch of impro, every instrument its own lead. You think it will never close, but it does. It is music speaking, pure. Extraordinarily pure: to to this day, no one knows who the flautist was on three tracks. He was just a session muso who turned up and was never needed again.

John Cale, who was recording in the studio next door — it was 1968! — said that Van couldn’t work with anyone, and that he recorded solo, with everything added later. This, it turns out, was untrue; horns and strings were added later, which is a lot of it, while the basics were laid down in single takes. That accounts for some gaps and weird spits in the tracks, desperate catch-ups. “Young Lovers” — derided at the time, as a piece of lounge-jazz, now bearing the spirit of its era, stylish as a Skidmore Owings Merrill skyscraper, slick as Pan Am — sounds like a race of order against chaos, a song purely driven.

Do I overrate it? It was No. 4 in an early ’80s list of the greatest rock albums ever, and I, wonkish even in this, was working my way through them — and stopped at No. 4. It was on the turntable all summer ’83 into ’84, when school was over and I knew I got into Arts and that was all anyone could want. It was a soundtrack to wandering the Georgian layout of Brighton, the hills, crescents and parks, fringed with Victorian ironwork terraces and Italianate towers, with my Brighton honey, a fifteen-and-a half-year-old who favoured brandy-and-dry and matte lipstick, looking for park benches on which to french kiss, and get hot and heavy beneath layers of Country Road calico. But that was the spirit of the thing. Life lives up to the art. And I only realised after writing the top bit that I had misremembered the role of “Young Lovers” in the album, which is actually the fifth track, start of the second side, not the first.

Van would go on to produce some great music; he never again produced anything like Astral Weeks. But who did? It was a one-off, sui generis, unclassifiable. It pays endless re-listening. It is 1968, or it’s one 1968, the year whose anniversaries can barely be contained within a year. I cued the thing up on YouTube to check something just now, and resumed writing 47.10 minutes later, born again, to be born again, on the bright side of the ocean …

The 2009 Live at the Hollywood Bowl version goes alright too.

Guy,

You nailed it. A unique recording of time & place. One of the most important & enjoyable albums of all time. I never tire of listening to this masterpiece.

S

yes indeed and still on my playlists. Madame George one his most evocative pieces ever…. “Throwing pennies at the bridges down below”

lovely guy, thanks, van is the man

Thanks Guy for reminding me of the strange brilliance of Astral Weeks. Truly one of the greatest albums ever recorded.