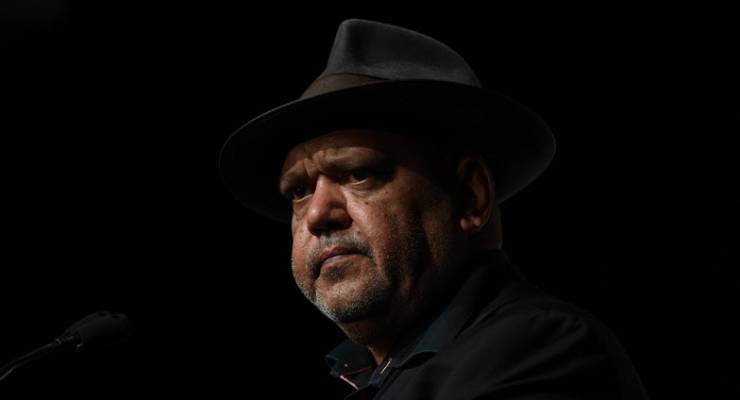

Noel Pearson

Last week, your correspondent asked a few questions about the “Uluru statement from the heart”, now a year old, and the proposed referendum question arising from it: one in which all Australians will be asked to authorise a particular quasi-parliamentary body, the Voice to Parliament, which, once embedded in the constitution, will have Indigenous representatives elected to it, and then negotiate a series of treaties between first peoples and settlers, to create a new Australian settlement. Your correspondent noted — as a potential voter on such — a number of questions about this: the tactical/strategic one of how such a baroquely complex political object would get past the fiendishly difficult process of a referendum, and what would happen if they achieved this wildly unlikely result?

My assessment was that the Voice to Parliament would almost certainly lose, and that if by some miracle it won, it would be an open target for the Coalition, who would paint it as a pointless talking-shop, and Labor, who would, judging by its record, condescend it relentlessly. These are questions that occurred not merely to me, as a seasoned political activist, but to many other “settlers” well disposed to a full treaty agreement: what was this Voice to Parliament? Where had it come from? For decades we had been lobbied to, and were willing to, support a treaty. One has just been agreed in Victoria, without an intermediary body being established. Now we were being asked to throw our weight behind a political Heath-Robinson machine, created in three days of discussion at Uluru, and presented as a fait accompli.

The article gained a boilerplate response from the national council, to which I replied. Business as usual, but little did your correspondent know that the very evening on which the article was published, Noel Pearson was speaking on this topic in Melbourne, to Melbourne white liberals, his last real fanbase, and explaining the plan in great detail. The Q and A, conducted with Megan Davis, included a five-minute personal rant about your correspondent, inaccurate in every detail, and bewildering to the audience, since Pearson failed to mention the article in question he was raving about.

That animus is largely irrelevant. What was significant was remarks about the post-Uluru process. “After Uluru, we got both our ducks in a row, and progressives should have got behind those ducks,” said Pearson, the Pericles of our time. He then grouched about the failure of major organisations to endorse the Uluru formula, moaning that groups like the Australian Medical Association had just come on board, and that the ACTU was yet to. The most likely reason was that organisations with large memberships felt it necessary to try and work out what the hell this thing was, before committing their scarce political capital to it.

What is striking about the response so far — to one article, which simply expressed one supporter’s basic bewilderment at the proposal — is the sheer arrogance with which such questions are greeted. This strikes me as bizarre. This writer will vote for pretty much whatever proposal is put on the ballot paper. But there are millions of others, well-disposed to notions of recognition, and (a lesser number) to a treaty, who will find the Voice to Parliament as bewildering as I have, in its arbitrariness, complexity, its direction away from the simple reciprocity of a treaty proposal, etc etc.

Surely, surely, answering the very basic questions I have about this proposal would be a useful exercise for the immense slog ahead, of selling the proposal to people like me? Is there some suspicion that even raising these questions is impertinent or bloody-minded? Is the proposition that a majority of votes and a majority of states will be won by a demand for unquestioning support for a proposal without much of a history or background? That is a big ask, even for a hardcore of non-Indigenous supporters. As a strategy for a double majority, it seems one of the most reckless gambles of all time.

There is much more to say about this, but for the moment one thing alone is worth mentioning. This is not offered, per se, as advice to Indigenous people, from that side of the debate. It is offered as raw response from the settler side, from which the vast majority of votes will have to come. It is offered within the basic framework that a treaty process creates: that it is not a historical award for effort by the conquerers to the conquered, as a way of writing off past sins. Nothing indicates a failure of the necessary reciprocity of treaty more than presenting a proposal that, to many, makes no damn sense. If Indigenous leaders want to spend the next few years shaking their heads in condescension at such, well then history to the defeated may say alas, but.

Well put Guy. Like you, I’d like to understand more and support getting something going to try for a good outcome. Pericles was responsible for locking the citizens of Athens up behind a defensive wall which probably helped most of them die from a plague of some kind; don’t know if that was worse than the predations of the Spartans and Persians.

The proposal for an indigenous parliamentary voice in the Statement from the Heart is not as hard to grasp as you, in such high but oh-so-nobly-contained dudgeon, may contend. The clue is in the word ‘voice’. It’s a matter of record that our elder Australians have never been listened to by the bewildering culture that so swiftly overwhelmed them, and from 1788 onwards have always been ridden over roughshod in the patriarchal imposition of Indigenous policy, which by definition exists under the tunnel-visioned imperative of economic expansion. Time and again we’ve heard and will go on hearing the lament of a once free, autonomous and culturally successful people who remain forbidden any effective say in their destiny. The NT Intervention was merely the most blatant form so far of an attitude of powerholders who have no understanding, empathy or sensitivity to a culture that abides in such diametric spiritual opposition to their material own that to countenance its principles borders on socio-economic sacrilege. Irrespective of a treaty, it’s this attitude that must change if this stolen land is to have any conscientious moral future, which must entail an enlightenment that seems unlikely on history’s record: the requirement that its more recent inhabitants should respect, adapt to, and actually feel the values of those who were its custodians since before mankind could even write. Moreover, there’s a tone of goodwill, sincerity and hope in the Statement from the Heart that’s strikingly different to your own, which exemplifies a petty, and, dare I say it, a pretty white narkiness. There’s a lesson for all of us in understanding that such a tone is one from which Statement’s writers, whose people have suffered a little more than being slighted in one man’s speech, very admirably abstained.

“Time and again we’ve heard and will go on hearing the lament of a once free, autonomous and culturally successful people who remain forbidden any effective say in their destiny.”

Nigel, what level of cultural success do you attribute to infanticide; cannibalism; endemic tribal warfare; and the kidnap of women as spoils of war?

You want to read some historical first hand accounts of Indigenous life in places like the Mary River in Queensland.

Jim, yes I’ve read them all and acknowledge there were unpalatable aspects of the culture in some (but not all) quarters, but which culture doesn’t possess its own brand of savagery? We could litanise crimes on both sides till doomsday, which (now that it’s cropped up in this correspondence) will certainly come sooner than later on western civilisation’s current trajectory. What the Statement from the Heart hopes to address is how to frame an honourable future together as descendants of both the perpetrators and victims of invasion and attempted genocide. First cultures the world over had a way of living that was not only harmonious with the environment rather than destructive of it, but was also not based on competitive materialism. For them poverty was an unknown state. How to live together, in fact how to survive as a species, is what we can learn from our Elder Australians, though it seems that this is an ideological challenge too great for many brains to contemplate. Yet the problem, which was once one of conscience alone, now concerns our own imminent and self-induced extinction: it’s become a universally existential issue that must be faced.

You’ll find Bruce Pascoe’s more recent research contradict’s most of that.

Perhaps the problem is that the first Australians are seen by this government as being “unauthorised maritime arrival(s)”, (see previous article) What’s sixty to seventy thousand years to the Turnbull tribe?

How likely is it that all, or even a large proportion, of those identifying as Aboriginal agree on any given topic, let alone one so pointless?

I cannot see why we would base suffrage on DNA – that is sooo 19thC.

Guy, you implicitly criticise Pearson for waffling but your piece could be criticised similarly. Indeed just what are the details of what Pearson is suggesting? Is Pearson advocating a system of Aboriginal Seats in Federal Parliament that is akin to the system in NZ?. At the time of creation (1867) the Maori Seats were intended as temporary. As an aside to satisfy The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 (UK) over 21 who were British citizens and met the individual property qualification could vote. Maori men could vote if they converted their (communal) land into individual titles. Thus electoral franchise made no distinction between settler and Maori.

For 50 years any Maori may contest or enroll in a non-Maori electorate, and similarly for any non-Maori to contest or enroll in a Maori electorate; thus making a monkey’s butt of the original purpose. Notwithstanding, with the advent of MMP the four Maori have a formula for representation. Having made that point the Deputy PM, Winston Peters, – among other prominent Maori – is seeking their abolishment just when Pearson seems to be advocating such a system! I wonder if Pearson ought to catch up with Peters in the relatively near future for a chat on the matter.

There is also the assumption that Pearson speaks for all indigenous people is contradicted by other indigenous people although he is credited with the misnomer “First Nations” that is vogue(ie) in North America. Then, as Windshuttle points out (Quadrant July 2017) “And while it is true the

Commonwealth could not make laws for Aborigines until the 1967 referendum was passed, that provision had no role in rendering Aborigines stateless or denying them citizenship. Responsibility for Aboriginal education, housing, welfare and labour conditions remained with the Queensland government which, at the time, was accused by most activists not of neglect or desertion but of paternalism and over-protection.”

In summary, I am rather hard put to determine the nature of the fuss; unless, of course, that if the clam by native title holders to 60 per cent of the country comes to be recognised then such a “council” of parliamentary representation will become the de-facto government – for anything is to be done at all.

(1) ought to read “males over 21 years of age who were British citizens ..”

(2) the Maori Seats were for those Maori males who had title and also had land in common.