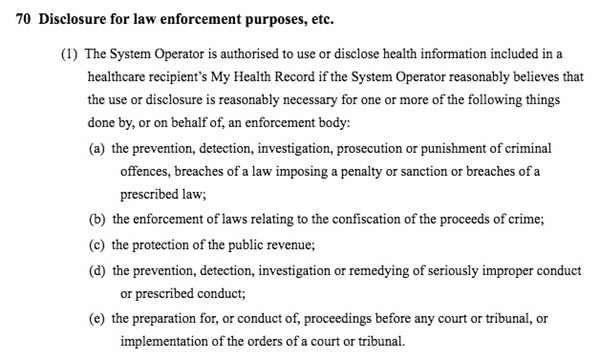

The latest front in the My Health Record controversy is that health records, if you’re foolish enough to allow one to be created for you, can be seized by authorities, including police, without a warrant. That can happen for “protection of the public revenue” or for “the prevention, detection, investigation, prosecution or punishment of criminal offences, breaches of a law imposing a penalty or sanction or breaches of a prescribed law”.

News Corp’s Sue Dunlevy summarised the problem perfectly yesterday, sparking scrambling by the Australian Digital Health Agency’s Tim “Long Live The Database State” Kelsey to insist that what was written in legislation wasn’t what the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) would, in fact, do. The ADHA, Kelsey claimed, would only release information in response to a “court or similar order”. Maybe agencies have that freedom in England, Tim, but here you don’t get to restrict what police and the ATO can access when legislation explicitly says they can get it. “A court or similar order” is basically a warrant, and there’s no requirement for warrant.

The warrant issue is a reminder that similar provisions are in the 2015 data retention legislation, allowing a range of agencies to access your telephone and internet data for “enforcement of the criminal law; administering a law imposing a pecuniary penalty; or administering a law relating to the protection of the public revenue”. Metadata is no less private than personal health records; a phone call to a medical specialist, or a reproductive health clinic, is highly revealing, except that the data from your phone extends far beyond your health. Health records have only very limited “network effects”, but combined your metadata with those of other people who may have a connection with you and far more information results than your most recent blood test. And all accessible without a warrant.

This might have the beneficial consequence of concentrating Australians’ minds about the ease with which governments can access their most private records — something that failed to happen around data retention. And that needs to happen because it may soon — within a matter of a few years — be impossible to have any meaningful life in an urban environment without leaving a dense trail of information that both governments and corporations will access. Your phone and — unless you opt out — your health records are just the start. Your internet search history is merely the beginning. Ubiquitous facial recognition technology is just around the corner, meaning both governments and, unless they are prevented, corporations will be able to see where you are in public (the first apps will be marketed to consumers as personal safety aids — e.g. see if there are any convicted sexual offenders around you). Even Microsoft is worried about the damaging potential of widespread facial recognition.

Then there is the growing autonomy of vehicles. Most new vehicles already have tracking technology, even if you leave your phone at home, never mind number plate recognition and toll roads. The growth of Internet of Things (AKA Internet of Shit, for its terrible security) devices in family homes not merely provides tempting targets for hackers but a potentially rich source of information both for manufacturers to on-sell and for governments to use from a location traditionally off-limits — the family home.

Within a decade, it’s possible that there will be no escape from corporate and government surveillance, from your home to the streets to transport to your workplace. Any information collected by corporations will likely be available without a warrant to authorities. You’ll be tracked everywhere, to be advertised to, to be monitored, to have your productivity and health maximised, to be told the best route/opportunity for consumption, to be manipulated, all without warrants or regulation. We’ll be reduced to data generators of no greater value than how we can be controlled to maximise our status as consumers and workers.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Government and corporations want us to think that’s inevitable, but it needn’t be, if we push back and demand dramatically more stringent, punitive regulation of corporate data-gathering and a blanket rule that governments need warrants if they want our personal information. In the meantime, opt out as quick as you can.

“if we push back and demand dramatically more stringent, punitive regulation of corporate data-gathering and a blanket rule that governments need warrants if they want our personal information”

One simple question: How? How do I, who already has a left leaning federal representative, cause any MORE of a push-back?

So we are not patients any more. Now we are healthcare recipients? I suppose George Orwell did try to warn us.

Australian Bill of Rights anyone? Legislation with such an alarming invasion of our alleged right to privacy would be impossible in most other liberal democracies such as the USA and the U.K. Their human rights are protected either constitutionally or by legislation, giving their Courts the right to protect civil society from the legislative excesses of their Governments. We have no such protection in Australia.

Good article BK but your call for ‘pushback’, while worthy, appears doomed. ” Metadata is no less private than personal health records; …. except that the data from your phone extends far beyond your health.”

We partied on or were too darned busy while our Government enacted the power to retain for 2 years, and investigate, our personal data records – mobile phone calls, internet browsing / usage and fax/ telephone calls. We didn’t push back as increasing numbers of government agencies obtained approval to access these records.

We gave Snowden’s statement no attention – ““Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.”

We have some of the worst intrusion of privacy legislation enacted in the world. Asking the OZ public to “push back” is a BIG ask. So sad, but we are now a docile lot.

As noted above, most people can’t be arsed because they literallyL have nothing of interest (even to themselves) to say or think about beyond the quotidian grind to feed the family and water the lawn.

Could be worse and, be assured, that it will be. Soon.

The only question is when will it be noticed?

My bet is Quoth the Raven’s – “Too late!”