There’s a great wooden canopy that overhangs in court two of the Supreme Court of Victoria — a vast high curve of polished dark wood with two enormous wooden sculptures of overflowing vases atop. Without it, the high-ceiling courtroom would dwarf proceedings. Instead, the dark wood, looming, cresting, gives off an ominous air, in keeping with the rulings of the law.

But for the past three days it has played host to a more pitiful spectacle, as one by one, dozens of people have come forward to a stand in the middle of the room, to give their account of the day, just on two years ago, when their life changed forever.

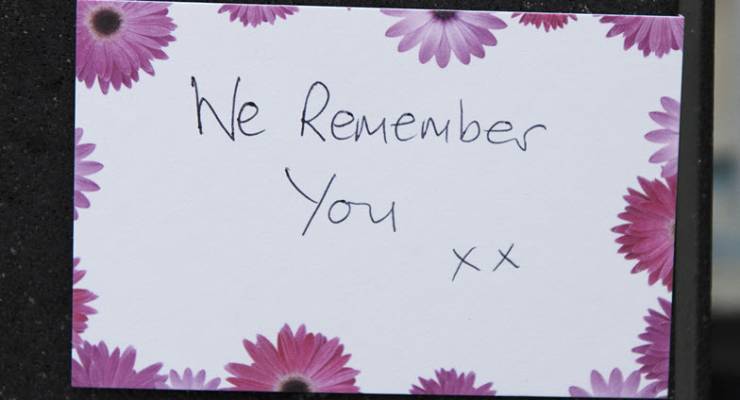

“I can’t walk along Bourke Street”… “I avoid that part of the city”… “I used to think that Melbourne was safe”… “I have to get used to catching up to my friends”… “I used to look forward to the weekend for his call, now the weekend is empty”… “without him my life is extinct!”… “I feel so guilty that I survived”… “I feel so guilty. I feel so guilty”…

This is the three-day pre-sentencing hearing for James Gargasoulas, who two years ago drove his maroon sedan (“I cannot see a maroon car without getting nervous”) up several blocks of Bourke Street between the mall and William Street, killing six people, injuring dozens and traumatizing hundreds more. Gargasoulas was convicted last year. Before the sentence are the victim impact statements. Three rows of people sit to one side of the court, relatives and survivors. They clutch the word-processed documents they are to read in their hands, tightly spaced Times New Roman.

“We went to the museum, and then we took the 96 tram back to the city,” said a parent of the three-month old baby boy who was killed when Gargasoulas’ car hit his pram full force. Some begin matter-of-fact and stay that way, some have essayistic reflections. “Since the 20th January I’ve lost myself and I’m trying to find myself again,” began Michelle Klobas, who was standing beside Jess Mudie when she was killed. On and on they come, those hit, those living on after the dead, the witnesses who can’t get it out of their head — “I saw bodies flying in the air, I couldn’t understand what was going on” — the first responders who had people die in their hands.

The court, its dark canopy, its benches, was never designed for this sort of thing of course — this mix of the raw human roar of pain and loss, mixed with striking moments of observation, and conventional clichés of TV and film. It was designed for impersonal “justice”, mostly the exercise of power, the imposition of impersonal order.

Throughout, Gargasoulas sits, minimally responsive. He’s heavier now than he was during the trial, and shabbier. On remand, he somehow managed to keep his hair styled with product in a sweeping jagged wave of the fringe, flashing as he glanced at the cameras while being loaded and unloaded from the court. That’s gone now. He is diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, was a long time ago; he has believed himself to be a messiah, and that people lived many lives. None of that was sufficient for a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. But that he is deeply disturbed, off in a private world, is a matter of public record.

Thus, even at the heart of this roll-call of suffering, there’s a paradox. To whom is it addressed? What could it redress? Few of the 30 or so statements that went through the court were directed at Gargasoulas himself. The report in today’s Herald Sun — ever determined to make the world slightly worse than it is — predictably and distortingly emphasises the one or two moments when relatives and survivors allowed themselves moments of vengeful rumination on Gargasoulas’ future suffering.

But for the most part, no one spoke of him or to him. They spoke of loss, they spoke of depression, and of more than depression: a sudden loss of interest in everything, a collapse of all meaning, really, as the world revealed — in absurd form, a hoon car, carving up a street — its utter indifference to what we love. Above all, they spoke of guilt, relatives, witnesses, medicos, cops, all. They all said it the same way, yet it never sounded at all faked or forced. Why did I survive and not her? Did I make the right choice? Could I have done more? Contrary to the two-minutes of hate the tabloids and TV news emphasise, what rose above the self-focus that victim impact statements — an instrument of justice whose specific form is probably long overdue a rethink — tend to produce, was a concern for the others, for strangers: “Could I have done more?”

All morning, all afternoon, such thoughts hit the hard canopy, bounced back into the court, had everyone leaving, at the end of the day, quiet and preoccupied, none of the bantering conversation you get in public galleries any other time.

The hearing, as they say, continues.

Your moving account points to the residual presence of a public forum where grievances can be “aired”, if not resolved. I really appreciate that Crikey can look at a story like this without the obvious moralistic response. It’s certainly a change from the way some Monthly writers visit the Supreme Court to perve on the poor, obsessing over cheap clothes and harried looks.

Powerful stuff GR.

People powerless to stop motor vehicles being used as weapons. Time to rethink motor vehicle access to CBDs and ease of getting a licence.

Definitely – the way to prevent loss of liberty is to abolish it, toot sweet.

And make it a crime to complain.

‘The report in today’s Herald Sun — ever determined to make the world slightly worse than it is…’

One of the things I don’t miss about Melbourne (having left around 6 months ago now) is seeing the headlines and front pages of the Herald Sun.

Great piece of writing, Guy.

“times new roman”

How do you know, you condescending dick?

Seriously Rundle, tighten up.