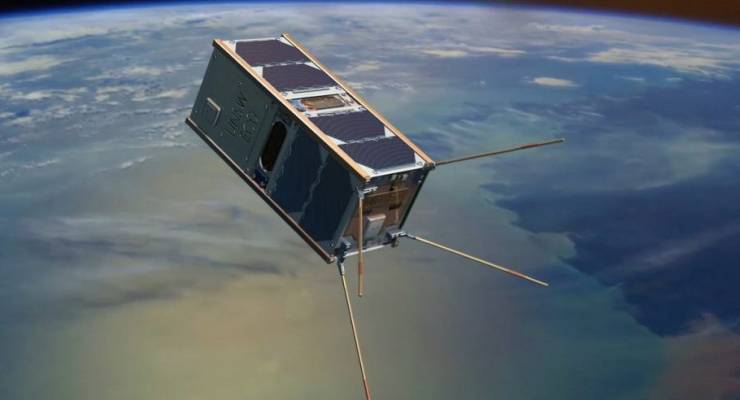

The commercial space industry sprung up in Australia virtually overnight. Cheaper commercial spaceflight and mass-produced satellites are leading to a wave of space start-ups flooding Earth’s orbit with new gadgets. One of the biggest new technologies is CubeSats. The name says it all. CubeSats are small, cube-shaped satellites powered by solar panels. Each CubeSat is 10 cubic centimetres and can combine into larger satellites.

Communications, research, and online mapping all use CubeSats. Their low price (you can have a three-unit CubeSat sent to orbit starting at $240,000) makes them popular.

Risks to a nascent industry

But there are risks to the rise of CubeSats. Illegal launching, satellite hacking, space junk, and communication band pollution all threaten this new industry. Created last year, The Australian Space Agency is part of a legislative clean-up of our pre-millennium space laws. Australian Space Agency head Anthony Murfett says “we’ve seen this rapid transformation that has seen commercial companies come in. Countries are now looking at their regulatory environments.”

With a flood of new satellites entering space, a flood of pollution comes with it. Communication band pollution and space junk — orbiting debris that collides with and kills satellites — could disrupt internet, GPS and many other services. Countries volunteer to sign international treaties, but there is little signatories can do if another country aims to grow its space industry by slackening regulations.

“There are five international space treaties in existence. Those treaties were set up in the 1960s and they were set up assuming it would be governments involved in space activities,” Murfett says.

Inovor Technologies is one company offering CubeSats in Australia. It recently helped design and build the CSIROSat-1, a research CubeSat for Australian coastal data. Inovor CEO Matthew Tetlow says “regulation is a problem because you can’t regulate another person’s space craft. The good citizen space-faring nations are looking to limit space junk.”

Defence robots in space

Along with pollution, space companies are in a military sphere. The Australian Defence Force increasingly contracts private companies. Like many other space companies, Inovor’s main business is space situational awareness and electronic warfare. “We monitor high-value assets that are very expensive to put up there. They’re strategic, communications satellites and internet for countries,” Tetlow says.

A spokesperson for the Australian Defence Force says, “the cube satellite program is aimed at enhancing Defence’s communications and situational awareness.”

It’s not as far-fetched as it seems. Last year, French Defence Minister Florence Parly accused Russia of spying on its Athena-Fidus military satellite. Destroying these hostile satellites would escalate Earth’s space junk problem. Instead, countries prioritise avoidance.

“If there’s a suspicious object near a strategic asset you need, then you don’t use it or make sure you have a backup. You change tactics,” Tetlow explains. But anti-satellite weapons are on the rise. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty prevents the use of weapons of mass destruction in space, but don’t mention conventional weapons. China and Russia have drafted a space weapons ban treaty, but the US didn’t sign. Since then, all three countries have continued space weapon research.

Another threat to space industry is hacking. CubeSats have off-the-shelf components and their user manuals are public. These generic parts are vulnerable to hacking. “Cyber is the next big threat. Premade pieces all have their own black boxes. You don’t know what’s going on inside those things. They could be sending your data anywhere,” Tetlow says.

Commercial satellites like Europe’s navigation network Galileo are used by both the public and military. Hacking Galileo would damage European phone navigation. It would also stop the EU coordinating attacks and missile systems.

As Tetlow sums up, “Communications systems are becoming more secure, but if it’s something somebody relies on you can guarantee somebody’s going to hack it.”

In low earth orbit, satellites and their fragments have a short lifetime of a year or so. The possibility of repeated collisions is low, so the ultimate density of fragments following each launch converges on zero. That’s Cubesat country. Higher orbits, well above residual atmospheric drag allow longer lifetimes. There the possibility of repeated collisions (fragments creating fragments) is much higher and the density of fragments increases until the zone becomes uninhabitable for new satellites.

‘Each CubeSat is 10 cubic centimetres’ – you mean each is 10 x 10 x 10 cm, i.e., 1000 cubic centimeters.

The head of the Australian Space Agency is the highest space administrator on the planet – earning at least double if not triple what the NASA Administrator gets paid.

But what else would you expect in a country that pays nearly all of it’s executive level public servants more than any other OECD nation does by 100-400%. And this is replicated across all three levels of Australian govts.

Well spotted. I can’t think of any PM or Prez paid more than ours – the fact that it has been the Abbottrocity and is now Mr Shouty just adds injury to insult.